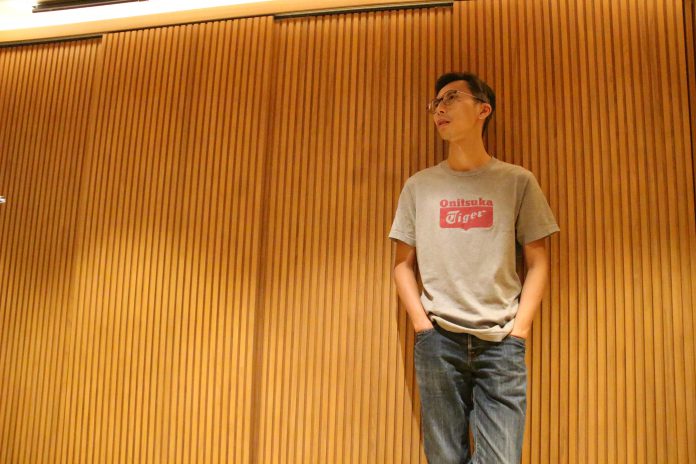

Director Chow Kwun-wai discusses his two popular films, Beyond the Dream and Ten Years, his strong character, and his lifelong goals as a filmmaker.

By Isaiah Hui

Beyond the Dream’s total box office exceeded HK $15 million and won Best Adapted Screenplay at Taiwan’s Golden Horse Awards – dubbed the Chinese-language “Oscars”. Despite these achievements, its director, Kiwi Chow Kwun-wai, thinks it is a difficult time for the film industry.

Chow says the pandemic greatly impacted the box office of Beyond the Dream as cinemas were temporarily closed because of the deadly coronavirus.

“The release dates of Beyond the Dream were suspended, and we had merely released our film for thirteen days. That period was crucial for promotion. When the cinemas were reopened after nearly one and a half months, the heat of promotion had already faded,” Chow says.

“Not only my film, but also other films’ box offices have been affected. Everything is interrelated. If my film’s box office is bad, it would affect me in the future if I want to find people to invest in my film. Those impacts exist,” the 41-year-old man says.

The director says impacts brought by the pandemic to film industry are a global issue, and people must wait for the end of the pandemic.

“Unless you want to film a recent story, when you film a street view and find that all passengers are wearing a mask, this kind of shot (could be problematic). I have also heard that some crews had infection cases, and quarantine was needed. So, many films haven’t resumed their works. They don’t dare to. They delay,” he says.

Ten Years

Chow is famous for directing one of the five short stories in Ten Years, a Hong Kong film depicting a dystopian future of the city, which was released in 2015 and quickly garnered international attention.

“The resistance is larger, so is the suppression.”

Five years after its release, Chow says the situation today is very close to the film’s prediction, “the resistance is larger, so is the suppression.”

“At that time (when Ten Years was filmed), we were arguing whether the scene of riot police beating people was exaggerated, but it turns out to be the norm today,” Chow sighs.

Despite this, Chow says it is encouraging to see many people are prepared to go onto the street although situation in Hong Kong was miserable last year.

“They are willing to sacrifice for Hong Kong. The film Ten Years uses the role of a self-immolator to ask a question about sacrifice: Someone is willing to self-immolate, how much do you want to sacrifice for Hong Kong?” Chow says the social movement in 2019 has given him an answer that further motivates him.

Chow, who is a keen Christian, says audience could hardly spot the Christian elements in Ten Years, “Most of the public screenings took place at churches and divine schools, and Jesus is actually another kind of self-immolator.”

He adds that he deliberately included the element of suffering in the ideology of both Beyond the Dream and Ten Years.

Chow is also determined that, as a film producer, he is obliged to film Ten Years.

“First, I have a religious belief and I am not scared. Second, I know I am not alone.” Chow attributes his determination to his own religion and the social movement in 2019.

Determination

“I hate examinations, but I asked myself whether I was willing to study for the sake of cinematography.”

Chow’s path to be a director is not a smooth one. Failed the English subject in the Hong Kong Certificate of Education Examination, he was forced to start working at an early age. He worked as a coolie, a CD shop worker, a mooncake factory worker and an ice-cream store worker before he decided to retake the public examination.

“I thought I could be a self-taught movie master, but I failed. I hate examinations, but I asked myself whether I was willing to study for the sake of cinematography,” Chow explains why he retook the exam twice in order to enter the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts (HKAPA).

“I remember the days in HKAPA when we had to do a film project with a limited budget. I was so determined that we must have a scene decorated like a household that I went to the waste station to pick out the suitable furniture,” Chow reminisces.

“Until last week, my parents still thought that my job as a freelance movie director was not stable, and they persuaded me to change to a full-time occupation. I didn’t listen to them as I really want to make movies. I even rejected an offer to work as a lecturer,” Chow says.

Future

Chow is pessimistic about the future of film production as the freedom of local film production has been limited since the advent of national security law. He describes this as “a future that we don’t want to see”, a line used in Ten Years.

Chow thinks that the room for creativity is narrowing, “The Office for Film, Newspaper and Article Administration asked the Inside the Red Brick Wall to open with a warning that its content ‘may be unverified or misleading’. Maybe it is just a start. Maybe more films will be banned because of political censorship,” Chow says.

The film documenting last year’s siege of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University was made by a collective of anonymous directors.

For movies produced in Hong Kong, Chow says they can be categorised into movies co-produced by Hong Kong and mainland film production companies and movies produced by local Hong Kong companies.

Chan fears that even films funded entirely by Hong Kong people would also cater to the taste of the Chinese market.

“Co-production film caters to the mainland market, and it has experienced (political) censorship; whereas local film doesn’t need to be censored. I felt that they have been merged as China wants ‘one country, one system’. I felt the risk of the ‘fusion’ of both movie types, a bad fusion,” Chow says that the inferior currency is now supplanting the superior one.

Speaking of his coming project, Chow says his next film will be about education.

“I am planning for a film about the education system. As what I have said, my childhood was rebellious. I resisted the education system. I have a strong feeling against an education system that stresses exams because I was a failure under this system, and it is also this kind of system that makes me endure a lot. I want to try this topic,” Chow says.

“Cinematography is my lifelong pursuit. I hope to film till I die,” the film director concludes.

Edited by Lasley Lui & Regina Chen