No easy money

No easy moneyImported labourers say it’s tough to earn a living here

No easy money

No easy money

Imported labourers say it’s

tough to earn a living here

By Kwok Kar Bo

He was hired as an assistant engineer for one of Hong Kong’s major infrastructure projects for 23 months.

Knowing that some workers, despite their posts, had to live in cartons due to the lack of dormitories, Ah-kin was satisfied to accept an apartment provided by the company in one of the Territory's industrial districts. To him, the first upsetting thing that happened shortly after his arrival was doing “an irrelevant job”.

Having studied industrial engineering and management at Hua Nan Polytechnic, he expected to learn more about management and advanced technology in Hong Kong. He hoped that such experience would be beneficial to him if he started his own business on the Mainland.

However, as an assistant engineer, he has had many other things to do: sweeping the floor of the office when he first came, then ordering concrete, preparing documents for the next day, and doing minor paperwork.

A specialist in industrial engineering, he has to deal with what he sees as the superficial work of civil engineering.

He feels that he is no different from a clerk.

According to Ah-kin, he works under the supervision of the foremen and has to obey their orders and maintain good relationships with them.

“I urged the employment agency to produce a document proving my post is that of an assistant engineer, but not a mechanic, as stated in the contract,” said Ah-kin.

Working hours and tension are also problems.

Concerning the working pressure, he said, “I can neither open an account to deposit my salary, nor mail it back home in China, since I have to work from Mondays to Saturdays. I can only leave my cash in a locker.”

According to the contract, there should be 11 statutory holidays annually and one day off in every seven days. But in fact, most workers work on holidays upon request by employers.

Ah-kin wants to rest on Sundays, although he feels quite lonely when he does take a day off.

“I am not familiar with places in Hong Kong. I seldom go out, but watch television. I can find nobody to chat with or play cards with, since we have to work in shifts,” he said.

Overtime work can lead to series of problems, including unfair payment.

Ah-kin said extra work on Sundays is usually not counted. Only after having worked for an extra 10 hours will they be paid overtime.

Moreover, even if there is overtime payment, the amount stated in the contract is equal to the payment for normal hours, instead of the common practice of 150 percent of the normal pay.

Moreover, even if there is overtime payment, the amount stated in the contract is equal to the payment for normal hours, instead of the common practice of 150 percent of the normal pay.

And this is not the only problem regarding salaries.

Ah-kin said many workers simply signed blank contracts and left them with the employment agencies in China. He said this was not because

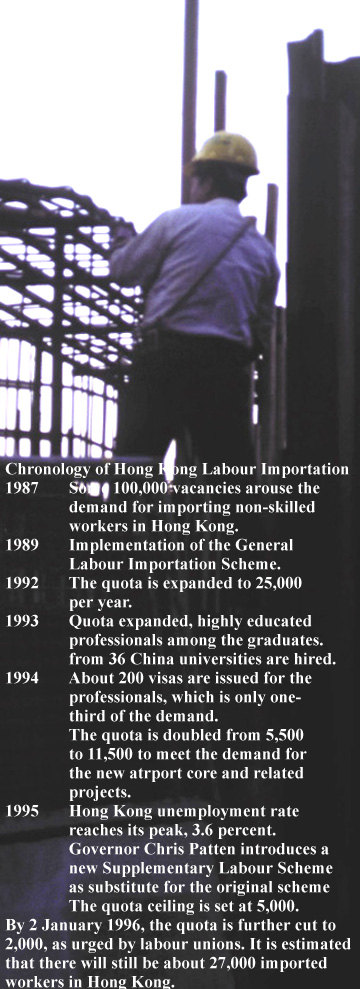

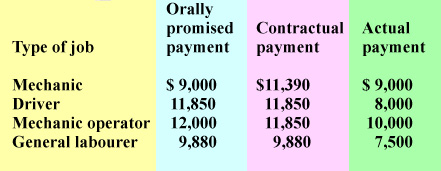

Promised and actual payments, according to imported labourers.

Promised and actual payments, according to imported labourers.

they did not know about the risks, but the risks were overridden by the belief that, no matter what happened, they could earn more in Hong Kong than on the Mainland.

As for himself, he was once orally promised by the construction company a monthly salary of $9,000 after deduction of the accommodation fees from the contracted amount of $11,390. He was quite satisfied with this amount.

But this was not the end of the story.

“Initially in China, the employment agency told me that I would be charged a total of RMB3,700 for the application and HK$1,000 for the passport,” said Ah-kin.

In addition, the employment agency charged workers about HK$900 for training courses, teaching them trivial things like not to spit or smoke at the workplace.

Nevertheless, after paying for the courses, the employment agency made the excuse that there were some “communication problems”, and some of the workers were then told that the proper sum should be HK$17,000. For some, the amount was even more. The remaining amount would be deducted from their monthly salaries for 23 months.

On arrival in Hong Kong, Ah-kin was approached by the employment agency and asked for this extra charge. The agency said this was the total administrative fee he owed. This almost stripped him of all his salary.

“The employment agency once phoned my mother in China, and she told me not to be a ‘troublemaker’ for safety’s sake.

“But I am only asking for what I deserve, not making trouble,” said he.

Ah-kin heard that some of his co-workers had even been threatened about being troublemakers on the very first day of work at the construction site.

Ah-kin himself suspects that the construction company and the employment agency might have some secret deals. They charge the workers in cash instead of drawing it from their accounts so that the Labour Department cannot check it.

Some can only glance at their account books, which are then returned to and kept by their employers. Cash is paid monthly by the construction company without any receipt.

Recently Ah-kin and his friends learned, though leaflets distributed by labour unions and news reports, that there was legislation pending. The day before this interview they questioned the extra charges and refused to pay employment agency. But some feared that they would be dismissed because of their refusal.

“The employment agency is like a bloodsucker, asking for money again and again. We may end up getting nothing after two-years of work,” Ah-kin said.

|

He got fired... By Kwok Kar Bo T he day after the accompanying interview, Ah- kin was fired by his company. The excuse was that Ah-kin hit a foreign labourer in October. But he claimed that this act was just a matter of self-defence. On the night of being fired, three men from the employment agency tried to carry him away from his apartment in Tuen Mun. In fear of being beaten — or even murdered — he dialled 999 before he ran away in his slippers, carrying with him several thousand dollars. The next day, he contacted the Neighbourhood and Workers Service Centre for help. During the last interview, Ah-kin said that he would not mind being dismissed, as he was not doing what he wanted to do anyway. He is now living with a relative. Usually, workers are allowed to stay 14 days after dismissal, but the Labour Department has allowed him to extend the limit in order to deal with his complaints. The Neighbourhood and Workers Service Centre suggested that Ah-kin hold a press conference, but he hesitates to do this as he worries about the safety of his family.

|