Mainlanders flock to Hong Kong bookstores to buy books censored back home

By Nectar Gan and Jennifer Lam

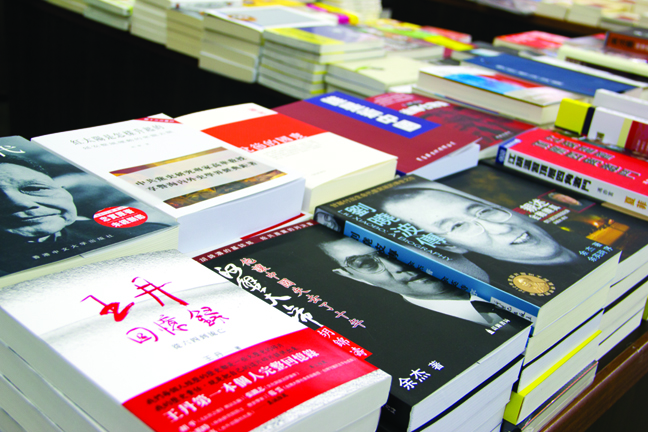

It is a weekday evening and Tsim Sha Tsui’s Peking Street is crowded with people and cars. But in an upstairs bookshop, it is extremely quiet. Thousands of books are arranged neatly on the shelves in historical order, from tomes about ancient times to contemporary China. Many of them are banned in the Mainland.

The Central Propaganda Department is the organ responsible for banning books in China. It has the power to censor, prohibit publication and ban the sale of books as well as to censor news, movies and television programmes. Banned books are often about sensitive issues in mainland China. They can range from academic works on political theory to salacious books of gossip about Chinese political leaders to fiction that is deemed morally suspect.

With such strict censorship in place, many mainland readers flock to Hong Kong for books they cannot buy back home.

On the evening of Varsity’s visit to 1908 Bookstore, Tim Wang bought two copies of Lishi de xiansheng, literally Herald of History. The book is a selection of speeches, articles and comments calling for freedom and democracy published by the Chinese Communist Party in the early 1940s, during the rule of the Kuomintang. The book has been banned by the Chinese government since 1999.

Wang grew up in the Mainland and came to Hong Kong before the handover. He is now in his 30s. He works in publishing and has a special affection for books. Wang says he has taken banned books back to the Mainland, either for himself or for friends,more than 10 times.

“I brought banned books as souvenirs from Hong Kong,” he says. In his eyes, banned books are much better gifts than mooncakes.

Wang says he was not always a big fan of prohibited books. He used to think such books were either poorly written or were just politically motivated. But his attitude changed after he read the historian Gao Hua’s acclaimed book on the Yan’an Rectification Movement, How the Red Sun Rises, out of curiosity. Wang recalls how he came to realise things that he had never paid attention to before. The more he read, the more he wanted to know. Soon, he was addicted to banned books.

For Wang, reading banned books is no longer just about satisfying curiosity. As China undergoes seismic changes, mainland society is struggling with many social problems. Wang hopes to get inspiration from books that are forbidden by the propaganda department, and be able to see a way out for the country.