How Kongish, a new term for Hong Kong English, is helping to redefine Hongkongers’ identity

By Tiff Chan

Do you understand the following sentences? “On earth, work hard ge not only have ants, but also have even lin ants dou ng hai ge Hong Kongers, working like slave every day. But many work slaves ng dare say, ng dare fight.”*

If you do, chances are you are fluent in English, Cantonese and what a group of post-80s Hong Kong English teachers are calling “Kongish”. The mixing up of Chinese and English elements in speech is nothing new. Chinese Pidgin English, also known as Chinese Coastal English first emerged in Guangzhou in the 17th century. It developed into a lingua franca between English traders and the Chinese they worked and did business with through the 19th century and into the beginning of the last century.

People in Hong Kong, with its colonial history, have long used English elements in their Chinese speech and Chinese elements in their English speech. For instance, it used to be quite common to hear someone use the word “inch” as both an adjective and as a verb to describe someone as arrogant or to say somebody is being sarcastic to someone else. This is because the character for arrogant, 串, is a homonym for 寸which is the character for “inch”, the unit of measurement. Although such usages have been around for a long time, the explosion of social media in recent years has led to a rapid increase in the creation and use of such expressions to form a distinctively Hong Kong kind of English, or Kongish. The rise of Kongish also coincides with Hongkonger’s heightened sense of local identity.

In August, three local English teachers and a company executive created Kongish Daily, a Facebook page sharing local news using Hong Kong English (Kongish). The site gained over 30,000 likes in three months. One of the founders, Nick Wong Chun, a lecturer at the Language and General Education Centre at Tung Wah College, says the friends had originally set up the page for research purposes. They were interested to see how people were using Kongish to communicate and were surprised by the enthusiastic response they received. The page has become a platform where people can use Kongish in an open public space.

Wong says the use of Kongish is on a spectrum, sometimes there are more Chinese elements and sometimes more English ones. Depending on the balance of elements, Kongish can either be close to standard English or to informal Chinese English, or Chinglish.

While this may make Kongish seem to be little different from Chinglish, Professor David Li Chor-Shing from the Department of Linguistics and Modern Language Studies at the Hong Kong Institute of Education explains that Chinglish tends towards non-standard English. Kongish, however, involves the use of Hong Kong-style English in which the syntax generally conforms to standard English, with recognisable Cantonese elements inserted to different extents. However, as Kongish is more informal than standard English or “High Cantonese”, users tend to be more lenient about mistakes in syntax and grammar.

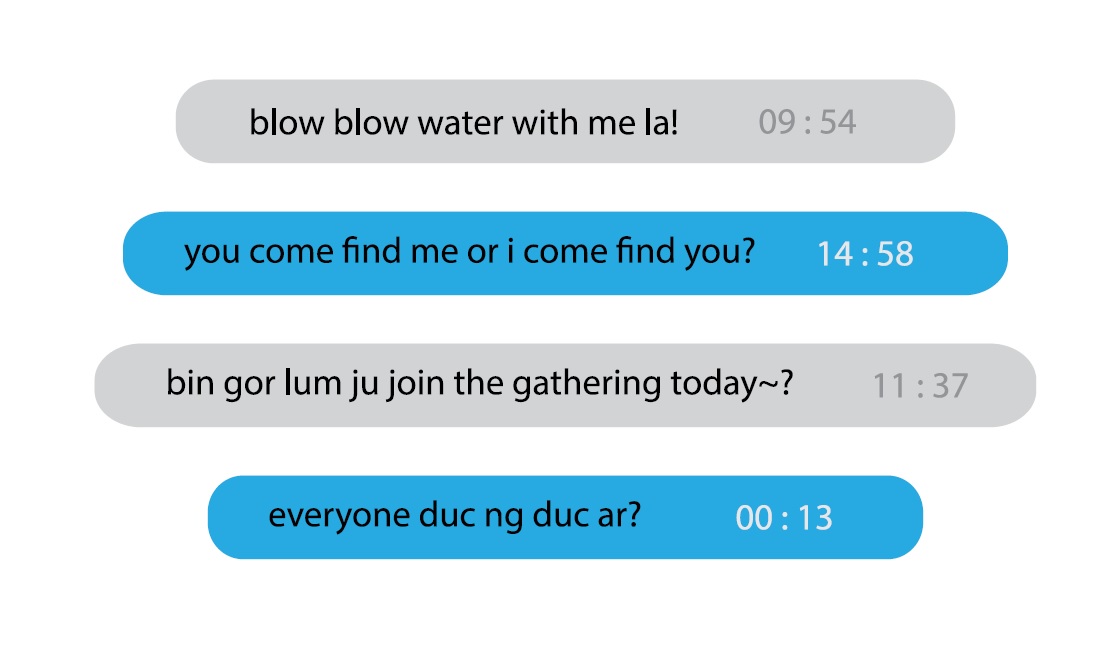

The growing popularity of Kongish over the years can be traced to the emergence of online communication tools such as ICQ. People who found it hard to type Chinese characters tried using English, Romanised Cantonese and the literal translation of Chinese into English in order to communicate. Given how widespread digital text communication has become in Hong Kong people, many have incorporated elements of Kongish in their messages. “If you do not use it, you are going against the tide,” says Kongish Daily co-founder Nick Wong.

Eventually, whether something is considered correct or incorrect usage will depend on whether it is accepted in mainstream society, says Wong. “Something said to be wrong becomes not so after it develops into a common practice.”