The implementation of the national security law has put the journalism industry at risk. Journalists and media outlets are now seeking ways to survive in the tight corners.

By Charlie Yip & Reus Lok

Protection of sources has become journalists’ major concern in Hong Kong after the introduction of national security law. “I won’t just phone call an interviewee whom I think is in need of high security. I will use applications such as Telegram or Signal to contact my interviewees,” says Ronson Chan Long-sing, the deputy assignment editor of The Stand News and the vice-chairperson of the Hong Kong Journalists Association (HKJA), says.

Signal is an instant messaging application currently on shelf with increasing popularity, especially among Hong Kongers after the law went into effect on June 30, 2020. It works just like other instant messaging tools, but with more security features such as end-to-end encryption for better privacy protection. To keep himself and his interviewees safe, Chan steps up security by using more reputable communication softwares and applications.

The national security law aims to prevent, stop and punish secession, subversion of state power, terrorist activities and collusion with foreign countries with legal accusation or even life imprisonment.

On August 10, 2020, Apple Daily founder Jimmy Lai, Lai’s younger son, Ian Lai Yiu-yan and a few executives of Next Digital Media, which is well-known for being critical of Beijing and the Hong Kong government, were arrested for alleged collusion with foreign forces.

About 200 officers raided the premises of the company in Tseung Kwan O and conducted inspection on news desks, sparking an outcry over the implications for press freedom.

Chan thinks that the law is generally seen as a menace to all media practitioners. “The law threatens freedom of speech and discourages people from voicing out their opinions,” he says. He also describes the job of journalists now as skating on thin ice and expects to see a decline in the number of outspoken media outlets which are critical of the government and Beijing.

“The law threatens freedom of speech and discourages people from voicing out their opinions.”

“Of course my wife and my parents are worried about me, but they’re well-aware of my passion and ambition for my job,” Chan says. He also reveals that he is mentally prepared for the worst.

Deterrent Effect and Panic

Cheung*, a free-lance reporter, shares Chan’s worries. She thinks ambiguity in the law allows flexibility for interpretation. “The law gives them a very convenient tool to curb press freedom,” Cheung says.

Cheung is worried and aware that some journalists have already self-censored their works to avoid falling into any legal trap.

“No matter what aspect a story is about, say education or entertainment, as long as it is associated with politics, people no longer have the guts to speak up. It makes the interviewing process much harder when even speaking the truth has such serious consequences,” she says.

“Holding the authorities accountable and informing the public are the two main responsibilities of journalists. Unfortunately, under the national security law, perhaps journalists can no longer serve the public, but the government. We have to report the truth even when we are facing an increasing risk,” Cheung adds.

“Unfortunately, under the national security law, perhaps journalists can no longer serve the public, but the government.”

Journalism is at Risk

The HKJA conducted a survey after the introduction of the law between June 8 and June 11. Of the 535 journalists polled, 98 per cent disagreed with the enactment of the national security law and 98 per cent were concerned about adverse effects on press freedom and expected stronger self-censorship.

Chris Yeung Kin-hing, chairman of the association, says that the concern reflected in the survey is well-founded. He cites wordings such as “incites” and “advocates” in some articles of the national security law as sources of worries, as reporters could be incriminated by wordings such as ‘incites’ and ‘advocates’ easily.

Hong Kong ranks 80 out of 180 in 2020 World Press Freedom Index as compared to 18 in 2002 when the index was first launched. Yeung expects a further decline in Hong Kong’s ranking in press freedom after the introduction of the national security law.

Yeung points out foreign journalists are having difficulties in applying for working visas in Hong Kong. On August 25, the Immigration Department denied a working visa application filed by an editor hired by Hong Kong Free Press (HKPF).

“The government has not explained this matter, but it is believed to be related to the law,” Yeung says. He expects to see a rise in the number of similar cases.

Varsity filed a question about the visa application of foreign journalists after the enactment of the law to the Security Bureau. “In handling each immigration case, the Immigration Department will consider the circumstances of the case and act in accordance with the laws and immigration policies”, the bureau says in a written reply.

“This may give foreign journalists an impression that Hong Kong is like China which expels foreign journalists or revokes foreign journalists’ working visas,” Yeung says. “We did not have this in the past, but it seems that there are signs showing that this is happening now,” he adds.

The HKJA, as promised by Yeung, vows to speak up and may take legal action against the government to defend press freedom. Yeung adds they will also remind their members to uphold professionalism to gain public support.

The Road Ahead is Lost

Journalism students are also worried that the law will have a great impact on their future career. Lcarus Chan, a journalism and communication major student of the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) and the president of the CUHK Campus Radio says, “To be honest, I may not work as a journalist after my graduation,” Chan says.

Citing the arrest of Jimmy Lai, Chan worries that reporting the truth may be considered as illegal by the national security law. “I study Chinese news reporting as I think it is worth studying. But it is hard to say whether journalists can continue to do their duty and serve the public in the future,” Chan adds.

Allan Au Ka-lun, a professional consultant of the School of Journalism and Communication of CUHK and a former journalist says, “Some principles have to be adhered and we should not scare ourselves at once.” “If we practice self-censorship out of fear, it is us who are giving up our values,” he adds.

“If we practice self-censorship out of fear, it is us who are giving up our values.”

Asked if the national security law will affect journalists doing reporting duty in Hong Kong, the Security Bureau says: Any measures or enforcement actions taken under the law must observe the principle that human rights including freedoms of speech, of the press and of publication”, the Security Bureau says in a written reply.

“However, the above rights and freedoms are not absolute, and may be restricted by law for respect of the rights or reputations of others, and for the protection of national security, public order (order public) and public health or morals,” the bureau says.

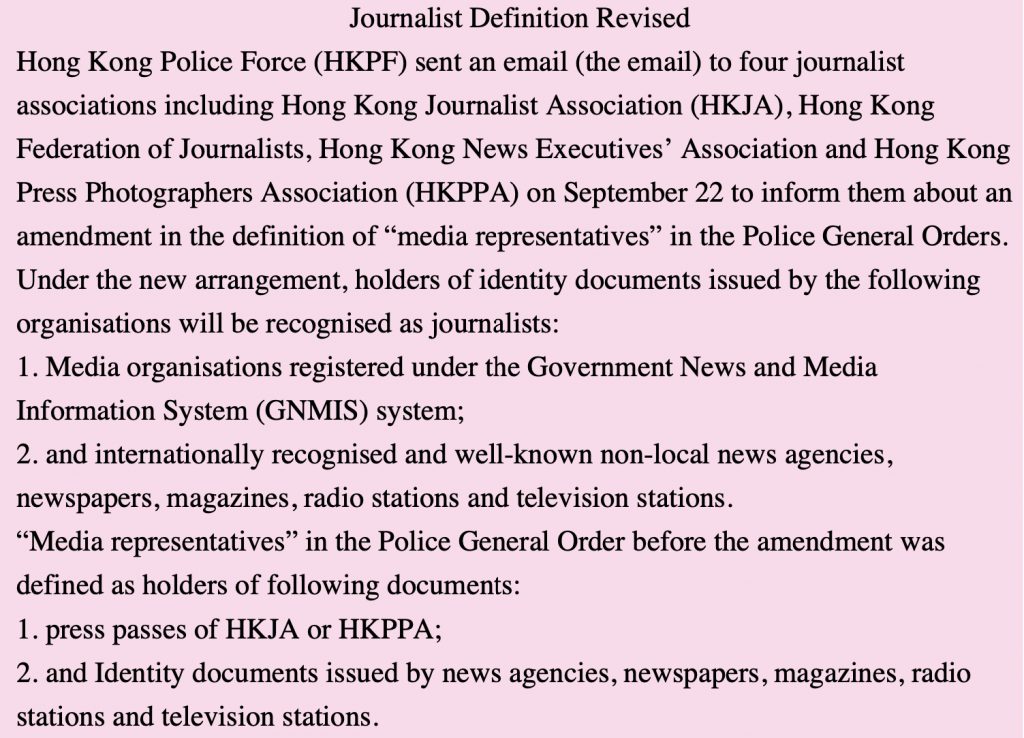

The amendment came into effect on September 23, one day after the announcement, without discussing and consulting HKJA or HKPPA.

HKJA, HKPPA, Citizen News Staff Union, Independent Commentators Association, Journalism Educators for Press Freedom, Ming Pao Staff Association, Next Media Trade Union, and RTHK Programme Staff Union issued a joint statement on September 22 to voice their opposition against the amendment.

“The amendment allows authorities to decide who are reporters, and this fundamentally changes the existing system in Hong Kong. It is no different from having an official accreditation system. The amendment seriously impedes press freedom in Hong Kong, leading the city toward authoritarian rule,” the statement reads.

“The amendment seriously impedes press freedom in Hong Kong, leading the city toward authoritarian rule.”

Chris Yeung Kin-hing, chairman of HKJA says the police have not fully explained why membership cards issued by HKJA are no longer recognised under the Police General Order despite repeated requests for clarification.

He points out journalists who work as freelancers, stringers, fixers and foreign freelance journalists are not on the list of the Information Service Department’s GNMIS system, their reporting job will be affected. They face higher legal risk when doing reporting in public places and may be liable to charges of offences such as unlawful assembly.

Ronson Chan Long-sing, the deputy assignment editor of an online news website, The Stand News and the vice-chairperson of the HKJA, says the amendment limits reporting duty of journalists working for online media outlets that are not on the list of GNMIS system.

The police explain that the new arrangement allows frontline police officers to recognize media representatives more efficiently in the email. Secretary of Security John Lee Ka-chu stresses the amendment does not affect the lawful reporting of journalists and the press freedom in Hong Kong has not changed in an article dated on September 23 on the Security Bureau’s website.

*Name changed at interviewee’s request

Edited by Emilie Lui