Migrant domestic worker finds strength in writing amidst struggles in Hong Kong.

By Lunaretta Linaura

Edited by Lorraine Chiang

Just like other migrant domestic workers, Ailenemae Salvador Ramos has to leave her family – including her husband and two children – in the Philippines as she works in Hong Kong.

But since coming to the city in 2010, Ramos has grown into a writer, an author and a co-founder of a writers’ group.

As a migrant domestic worker, she finds it difficult to talk about heavy topics to her family and other workers. So in her free time, Ramos reflects on and records the details of her daily experiences through poems and short stories, mostly written in English.

“We cannot talk to our families about how we feel being away from them, because we don’t want them to feel sad. I don’t want my family to know I am not happy here,” the mother of a 17-year-old son and a 19-year-old daughter says.

“I keep it in my journal, and it makes me feel better. At least I have paper and a pen to help me understand what I’m really feeling,” the 40-year-old worker adds.

Ramos’ employers encouraged her to publish a book by sponsoring the publication.

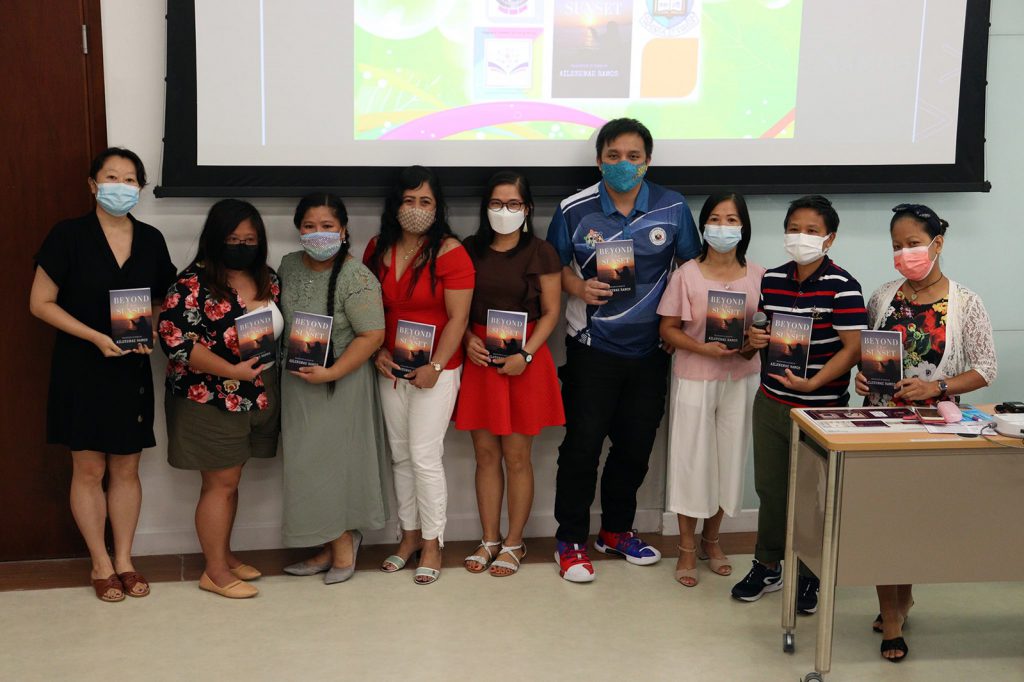

In 2021, Ramos’s first book, a poetry collection, “Beyond the Sunset” was published by Poetry Planet Publishing House. She dedicates the book to her mother who passed away when Ramos was two years old. As a child, Ramos’ relatives made her believe that her mother was “beyond the sunset”.

Ramos’ book reveals her personal experiences and the collective experiences of women and migrant domestic workers – being away from their children, finding confidence in being a “simple woman” and the optimism through it all.

“[My book] is my life story. Growing up, marriage, my aspirations, dreams for my children, migration story, pains, anxiety, depression. It’s everything,” she says.

“I honestly did not dream of being a writer. When I was a child, I actually dreamed of being an accountant to follow my mother’s footsteps,” she adds.

However, to sustain her family, she came to Hong Kong as a domestic worker. The minimum allowable monthly wage for migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong is currently HK$4,870 (US $623.64), while the low to average monthly income in the Philippines ranges from HK$1,530 to HK$6,060 (US $195.93 to US $776.02).

Having stayed in Hong Kong for 14 years, Ramos has worked for six different employers. She has no plans to return to the Philippines soon.

“I need to make the sacrifice despite the homesickness I feel. If I don’t make the sacrifice, my family will have no food to put on the table,” she says.

Ramos had a difficult time adjusting to her new life in Hong Kong.

“It was hard to stay with a stranger’s family and take care of their newborn baby whom I treated as my own. It was really hard since I myself have my own children, who were around 4 and 5 years old, whom I left in the Philippines,” she says.

Ramos’ fourth employer gave her the most difficult time. It only took three months before Ramos terminated the contract.

“Every day, [my fourth employer] called me ‘stupid’, ‘liar’, ‘dumb’. I couldn’t take it. It was torture,” she recalls.

Luckily, Ramos has also worked with supportive employers. She highlights how valuable they are in getting her to where she is today.

“They encouraged me to join activities, even on weekdays. I have never once received a ‘no’ from them… They believed that participating in events helped me improve myself… to inspire other migrant domestic workers,” she says.

In 2020, Ramos became acquainted with students from Singapore through a financial management online course. Through their introduction, she joined the Migrant Writers of Singapore — a writers’ group composed of migrant domestic workers in Singapore.

“I participated in writing and sharing poetry in their Facebook group. I joined their poetry reading and storytelling sessions every week,” she says.

Ramos also joined creative writing workshops held by the University of Hong Kong.

“[At the time of the writing workshops], I kept on writing. I improved my diary entries, rewrote them, and wrote them through poems and short stories. When I checked my notes app, notebooks and writings on Facebook, I’d written around 100 poems.” she says.

Ramos hopes other migrant workers can find the same resilience she found in writing.

Inspired by Migrant Writers of Singapore, Ramos co-founded Migrant Writers of Hong Kong with friends and fellow migrant domestic workers, MariaNemy Lou Rocio and Liezel Marcos, in 2021 just before publishing her own book.

With over 3,000 members now, Migrant Writers of Hong Kong conducts writing workshops for migrant workers and hosts a Facebook group where they can upload their writing.

“We wanted to start a community where [migrant domestic workers] could freely share their experiences and emotions without burden. Not all migrant domestic workers are confident to share their stories publicly. They may be scared to offend their employers with their stories,” she says.

“We think if other [migrant domestic workers] read the posted writings, they can relate to it and think ‘if she can survive this, why can’t I?’” she adds.

Through Migrant Writers of Hong Kong, Ramos aims to widen other migrant domestic workers’ horizons, not only through gaining new skills and engaging with literature, but also to inspire them to share their migration stories with confidence.

In March 2024, together with other photographers and sketchers who are also the city’s migrant workers, Migrant Writers of Hong Kong launched an anthology, Ingat, meaning “take care” in Tagalog.

Ingat showcases poetry, photography and visual art created by migrant domestic workers. All written pieces include Cantonese translations so that the artists will be able to be understood by more people in Hong Kong.

Ramos believes that writing can promote inclusion of migrant domestic workers in the city.

“I want us to voice out our stories for employers and the wider Hong Kong community to understand the true life and struggles of migrant domestic workers, that we are also human beings,” she says.

Although Ramos has no plans to publish another book soon, she continues to promote writing through Migrant Writers of Hong Kong’s writing workshops.

“I want [other migrant domestic workers] to understand that being in Hong Kong doesn’t mean only being a domestic helper. While working with our employers, there is more to do during our free times,” she says.

“We are not just domestic helpers. We are more than that. We can do more,” Ramos adds.