No explanation is given in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum about why Japan was attacked by atomic bombs.

By Daniel Koong and Winnie Li in Hiroshima

University student Mike Chu Chi-hei feels frustrated after visiting the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and wonders why there are no exhibits explaining why two atomic bombs were dropped in Japan.

“When I walked out of the museum, I realised the exhibition did not talk about how Japan started the war and the war crimes they committed,” Chu says.

“I feel like the museum management intentionally keeps war crime elements out of the exhibition. The focus is all about portraying Japan as a victim of the war without showing visitors the causes of the war,” the journalism major student says.

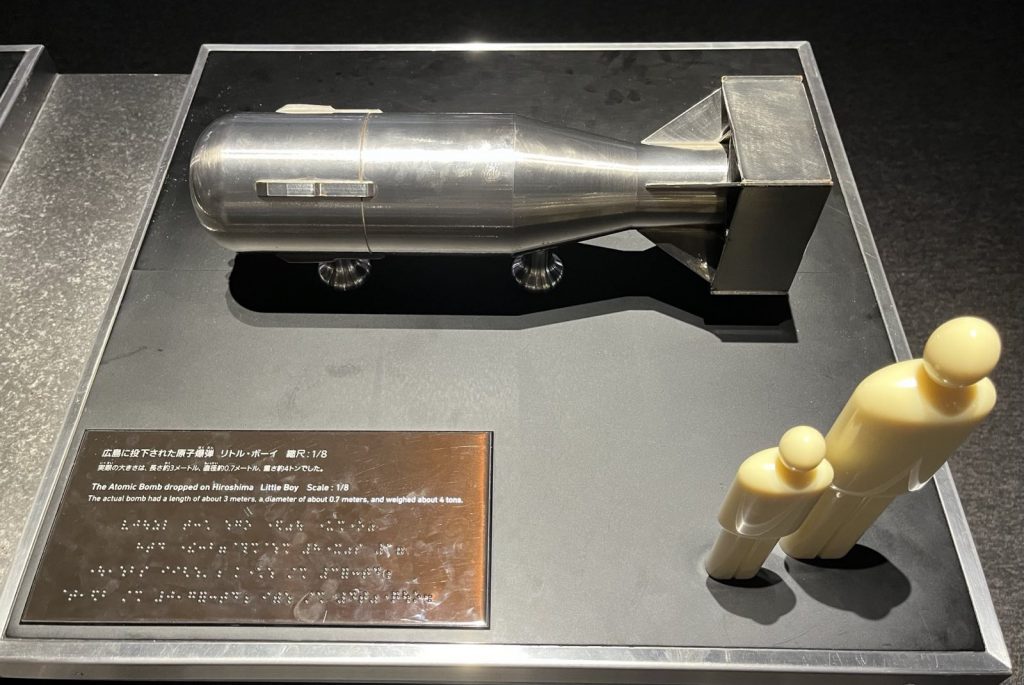

Hiroshima was the first target of a nuclear weapon in history. The bomb dropped on Hiroshima, named “Little Boy”, was 3 metres tall with a 0.7-metre diameter.

Another bomb, “Fat Man”, dropped on Nagasaki, was 3.2 metres in length with a 1.5-metre diameter. The United States deployed both bombs during World War II.

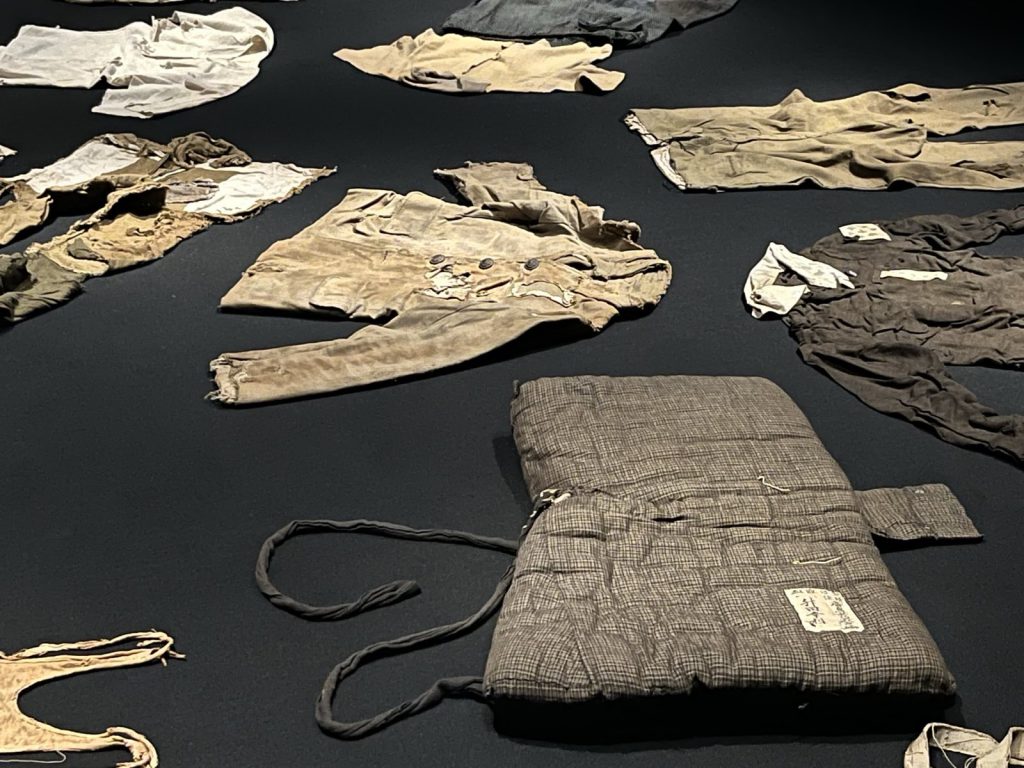

Built in 1955, ten years after the end of World War II, the museum is dedicated to documenting the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and promoting world peace, and displays artefacts and belongings left by the victims of the atomic bombing in Hiroshima.

According to data from the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, from January to September 2024, 162,019 people had paid a visit. Schools arrange tours for students to visit the museum.

Exhibition in the museum starts with how Hiroshima was destroyed by the atomic bomb. Pictures and photos of victims’ injuries are displayed. Visitors can also see victims’ personal belongings and clothes.

The museum covers details about the Manhattan project that created the atomic bomb.

Chu questions why Japan cannot learn from Germany, imperial Japan’s wartime ally, publicly admitting their war crimes in the museum after the war.

“I don’t understand why Japan still does not admit that they were wrong in World War II, they are still hiding the truth from their people,” Chu says.

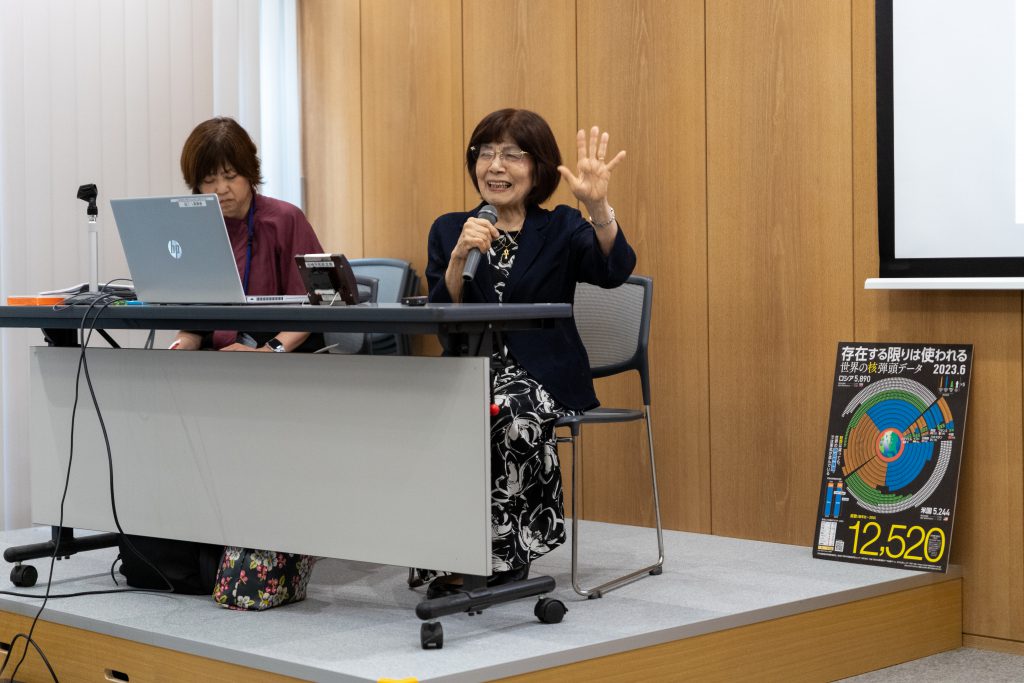

Like Chu, atomic bomb survivor Teruko Yahata thinks it is important for young people to learn about causes of the war.

Yahata did not know why Japan was bombed until she participated in the Peace Boat Hibakusha Global Voyage in Singapore in 2013 when she was 75. She is now 86.

“I was so shocked to learn about that. I didn’t know much about Japan being the aggressor during World War II… I think it is necessary for Japanese students to learn about the history as well as the cause and result of the war,” the Hiroshima resident says.

Assistant Director of the International Peace Promotion Department, in the City of Hiroshima, Ryoji Hasebe, thinks that the most important role of the museum is to inform the public of the horrendous impact of the atomic bomb on humans.

“The displays explain our strong wish for a peaceful world and how we seek peace. What we want to tell through the exhibition of the museum is not that Japan was not victimised by the atomic bombing. We want to emphasise that if nuclear weapons were used again, these kinds of things would happen again and might happen to anyone anywhere,” Hasebe says.

Professor Edward Vickers, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation Chair on Education for Peace, Social Justice, and Global Citizenship, comments that it is important to the truth.

He also points out that selective speaking of history is dangerous for the peace and stability of East Asia.

“I think that the result of the failure to confront young Japanese with the truth about atrocities committed by imperial Japan during World War II is enduring hostility and suspicion in relations between Japan and its closest Asian neighbours – Korea and China,” he says.

“Of course, Japan is not the only nation using public history and schooling to tell a story of national ‘victimhood’; China and Korea do this, too. This intense focus on victimhood, with Japan, China and Korea all claiming that they are the supreme ‘victims’ with a special understanding of the horrors of war, creates a deep intolerance of other people’s stories of suffering,” he adds.

Regarding the comparison often made between Japan’s and Germany’s reactions to World War II, Professor Ran Zwigenberg, Associate Professor of Asian Studies and Jewish Studies at Pennsylvania State University, says the museum in Japan should not be compared with Germany.

“There is indeed a difference in the post-war history of the two societies and the reaction of their political establishments but one should not talk about ‘Germany’ or ‘Japan’ here but in terms of different times, political parties, and groups,” Zwigenberg says.

He points out that, as German political elites had to reintegrate themselves into the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation alliance and the European Union, they had to “solve” the moral and compensation issues vis-a-vis Western European countries as well as the Jewish victims.

“Unlike Germany, Japan could separate itself from the rest of Asia as there was no political and diplomatic incentive to be as open as the Germans about this. The US supports Japan, unlike Germany,” he adds.

Edited by Carrie Lock

Sub-edited by Molisa Meng