The Community Care Service Voucher Scheme offers seniors a new lease on life, blending care, connection, and independence.

By Belle Yip

Going to day care service three days a week, Sean Pui-kwun hopes to grow old in his own home with his family.

“I don’t think I urgently need to live in an elderly home,” Sean says.

Once a taxi driver, Sean is now an 89-year-old retiree. He likes wandering around the community, but the strength of his legs is deteriorating gradually. Now, a 15-minute walk is his maximum.

An accident last year made Sean understand he should keep a close eye on his health. “I fell onto the ground when leaving my building. My elbows kept on bleeding that day. My wife and my daughters were frightened,” Sean recalls.

For about half a year after the accident, he needed the company of his daughters or his wife whenever he went out for a walk or lunch. “I thought I was a burden to my family,” Sean says, adding that having day care services has revived his life as his health has slowly improved.

The accident triggered his daughters to think of finding a day care centre for their father. The daughters helped Sean apply for the Community Care Service Voucher Scheme for the Elderly (CCSV) after being advised by a social worker.

Under the CCSV scheme, elderly can obtain services such as speech therapy, personal care or rehabilitation exercises provided by government-recognised organisations. The government subsidised day care and home care services based on household income.

Sean pays HKD$204 for each visit to the day care centre. His family wishes the government could subsidise more.

Every Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday, Sean spends half of the day at Woopie Club (To Kwa Wan), a daycare centre in the community.

“I can still spend some time on the streets and have dinner with my wife after the centre visit,” Sean says.

Sean loves hanging out in the centre to stay active. “I like doing calligraphy. The centre provides me with brush and ink so I can do some practice,” he says, adding that he also likes tossing bean bags and playing cards with other elderly.

Photo courtesy of Woopie Club (To Kwa Wan).

“It’s great for socialising and making new friends. And I feel there is something I can do and long for,” Sean says.

While Sean feels happy about his time in the day care centre, other family members share his joy and that makes the family become more harmonious.

“It’s all about having more me-time,” Sean’s wife, Li Ching, says with a smile.

Noting that day care services reduce unnecessary arguments, Li, in her late 70s, adds, “Life feels a bit lighter that way.”

Yan Che-kai Brian, vice case manager of Woopie Club (To Kwa Wan), says the day care centre is just like a clubhouse for the elderly.

“They can hang out with each other to enjoy their retirement life. With similar ages, they can easily make friends with each other,” Yan says.

The centre provides lunch and muscle-training exercises. The exercise is complementary to those provided by hospitals, which help speed up rehabilitation.

He adds that activities for the elderly are tailor-designed. Seniors with similar conditions and backgrounds have similar training. The importance is to train their cognitive ability.

“Elderly women who used to be factory workers engage in related nostalgic therapy like gardening therapy and shoelace tying,” Yan says.

Photo courtesy of Woopie Club (To Kwa Wan).

Although many elderly people in the centre love its services, the number of centres providing the day-care service dropped after the regularisation of the scheme in 2023, according to Yan.

Yan explains that most elderly and their family members still hold the traditional belief that they prefer services like meal delivery and companionship services, and they are less interested in rehabilitative activities and cognitive training at day centres.

Dr. Fong Meng Soi Florence, senior lecturer of Asia-Pacific Institute of Ageing Studies (APIAS), shares Yan’s observation. She points out that many elderly and their caretakers found the CCSV scheme too complicated.

“They don’t know how to choose authorised service providers in the long list,” Fong says.

Fong thinks it is important to educate caretakers. “Caretakers are the ones who make the decision,” she says. She points out the caretakers seldom study each provider when making a choice and not many social workers provide one-stop service for each case.

As of January 2025, there are 297 Recognised Service Providers under the CCSV scheme as stated by the Social Welfare Department.

Fong says some of the authorised providers may fail to provide services some elderly need and small-scale centres are unable to make money from admitting elderly under the scheme.

“With only five to six cases, the small-scale ones cannot bear the cost. They then turn to focus on other services that are profitable,” she says.

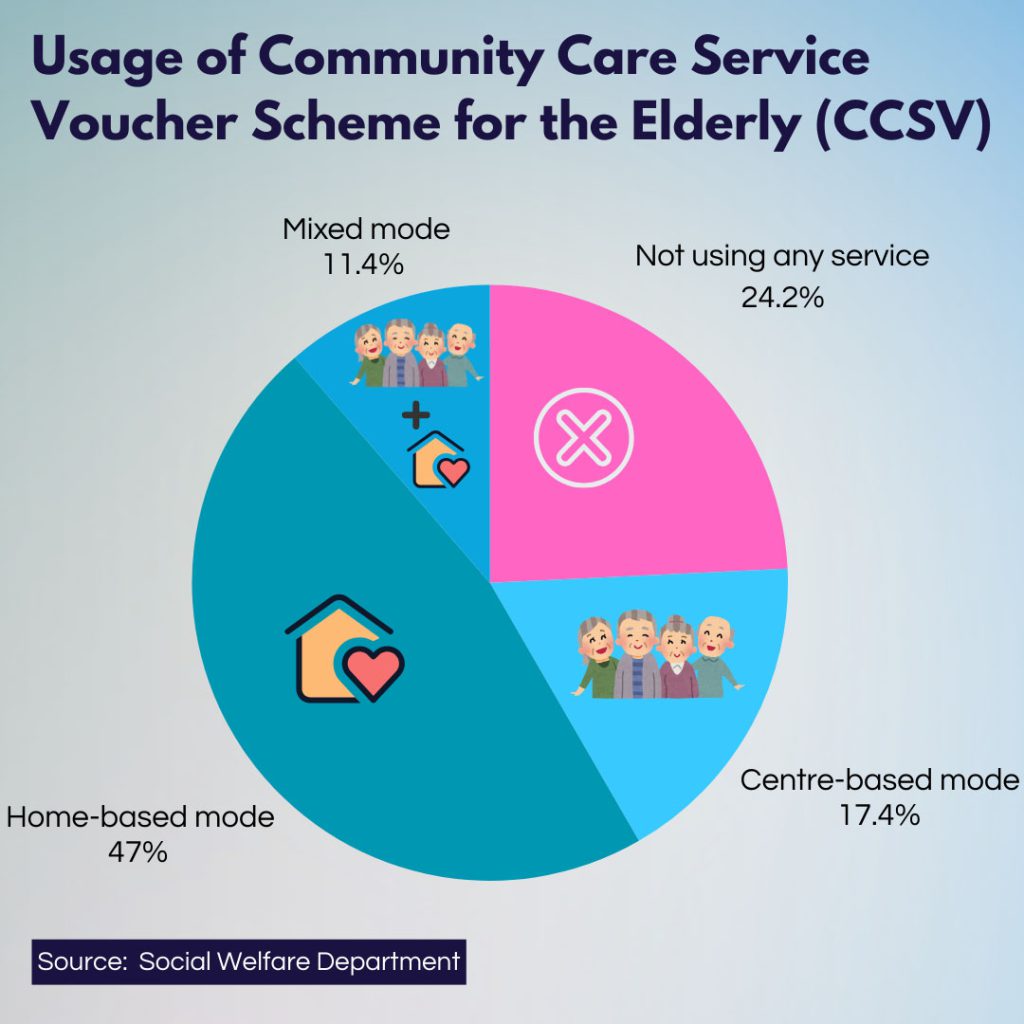

A survey conducted by the Social Welfare Department (SWD) reveals 16,402 elderly received CCSV until November 2024. Among them, only 68 per cent were using the service whilst the rest were not receiving any service at all.

As announced in the latest Budget, the government will raise the number of CCSV recipients by 1,000 to 12,000 in total, involving an annual expenditure of about HK$900 million.

Fong welcomes the new move.

“The scheme is public service for the elderly in Hong Kong that allows them to age at home. Nothing can compare with the happiness of mingling with other elderly,” Yan says.

Edited by Celina Lu

Sub-edited by Angel Yu