Legislative Council President Jasper Tsang Yok-sing is as disappointed as many pan-democrats by Beijing’s hardline decision. Tsang is considered one of the more open-minded pro-Beijing politicians in Hong Kong. He was one of the 39 moderate pro-establishment figures who signed a petition calling for consensus on political reform in early August. This was when Occupy Central was getting widespread coverage and heated debates on possible election packages were raging among lawmakers and scholars. The petition was an attempt to draw the pro-Beijing camp closer to middle-of-the road opinion leaders.

“By rejecting any popular candidate, the price Beijing has to pay is the election will lose credibility,” Tsang says, yet he also knows why Beijing cannot promise Hong Kong a liberal electoral framework. “The risk is someone, Beijing believes, who will cause a lot of troubles for Hong Kong may be elected,” he says. Tsang hints Beijing may have a hard time ruling Hong Kong, especially on sensitive issues, if the top post is held by a pan-democrat who has “no intention of cooperating perfectly with the Central government”.

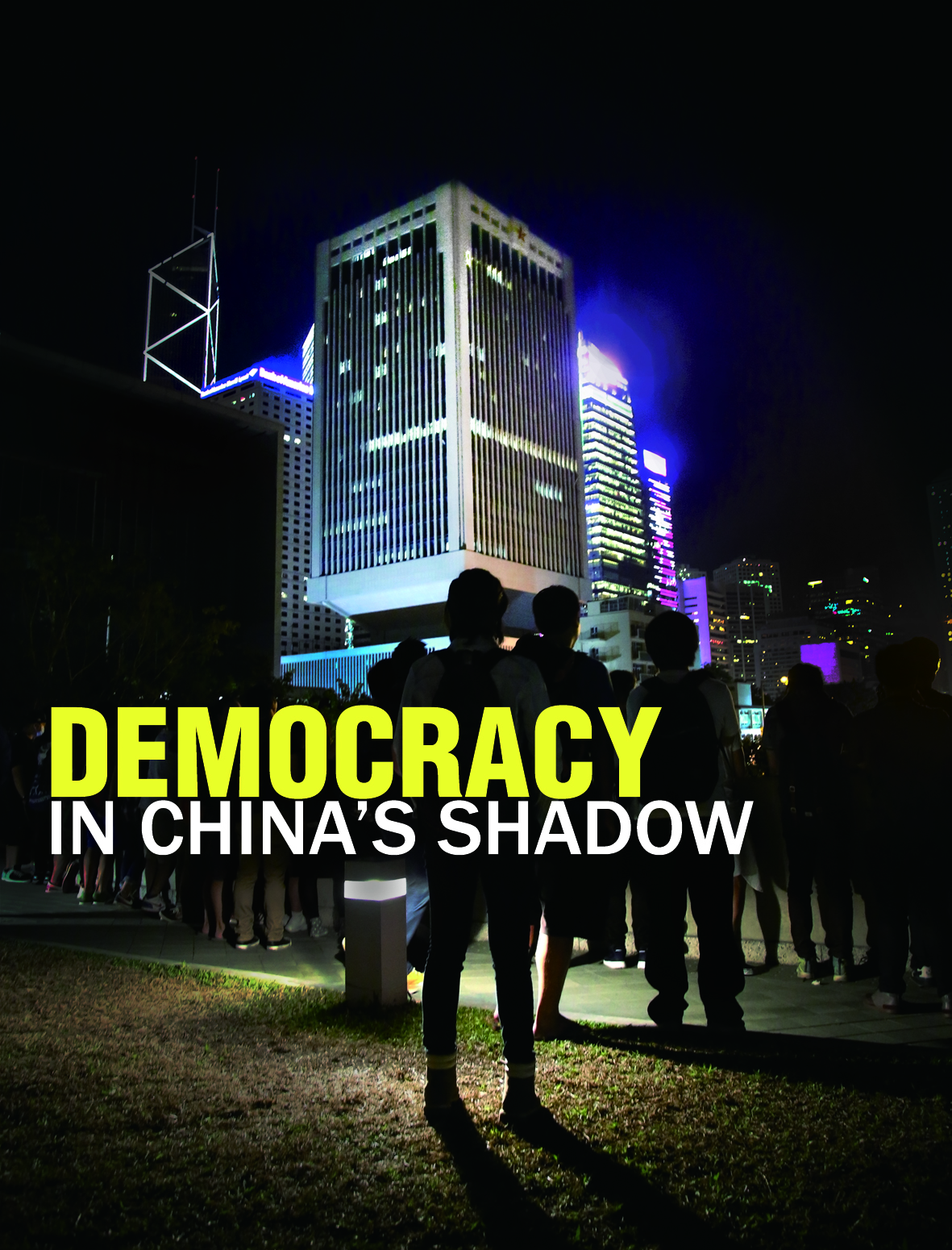

As Beijing risks damaging its legitimacy in Hong Kong by pushing forward a version of universal suffrage many find unacceptable, democracy advocates are taking to the streets against high-handed governance. Tsang believes civil disobedience should never be a way out of the political deadlock. “Both sides have adopted a tactic of muscle showing. Power-play, rather than engaging the other side in meaningful dialogue. It only causes a spiral towards worse confrontation,” he says.

At a time when many have lost faith in the Beijing-dominated universal suffrage discussion, Tsang insists there is still hope and space for negotiation, but before anything can happen, Beijing should provide enough incentive for pan-democrats to return to the negotiation table. “We have to explore issues [on universal suffrage] that Beijing is willing to concede to, willing to talk about, and which the pan-democrats will find worthy to talk about. If it’s just a minor adjustment of the composition of the nomination committee, it’s not enough,” he says.

Unlike Tsang, some have given up hope on Hong Kong’s democratic prospects. Dick, 23, a fresh graduate from Polytechnic University who does not wish to disclose his full name, used to be active in street protests. Like many young people of his age, he took part in the June 4 vigil, the July 1 demonstration and in the anti-national education protests in 2012. But increasingly, he feels powerless and apathetic about Hong Kong’s political reality.

“You can see China has a firmer grip on Hong Kong,” Dick says. “Though people take to the streets and protest peacefully as usual, I think these are just sound bites and slogans, with little effect,”

Dick thinks only when people dare to give up their lives for political change will sufficient bargaining power for the opposition be created. Yet most protesters are unwilling to risk their careers and families for democracy, and neither is he. “I have some feeling [about politics]. But I control it. You still have to work tomorrow, you still have to go to school, unless you give up all other things,” he sighs.

When Professor Benny Tai Yiu-ting laid out his plans to Occupy Central last year, Dick was impressed by his notion of civil disobedience. But his faith in the movement gradually eroded when he realized that no matter how many people took to the streets and how many roads got blocked, the authorities would never back down.

“Just voicing [your opinion] is far from enough. People sit there and wait for somebody to lead them, guide them … it has to be much more than the current stalemate,” he says after witnessing a week of occupy movements. Convinced there is nothing he can do to change the political situation, Dick is now considering emigrating to a European country with his family, leaving behind the dim political future of his birthplace.

October’s occupy movement is an outburst of public anger that shows Hongkongers’ determination to gain genuine democracy through non-violent means. At the time of writing, sections of the city’s busiest business and shopping hubs remain occupied. The number of sit-in protesters has dwindled only to swell again after police and anti-occupy groups forcibly removed the protesters’ barricades; resentment about the disruptions to daily life grew and some of the occupied roads reopened. After weeks of false moves and recriminations the government and student representatives finally held talks.

But there was no immediate sign of a breakthrough. The government said it would consider submitting a report on the views expressed in Hong Kong since the NPCSC decision and set up a multiparty platform to discuss political reform after 2017. This satisfied neither the student representatives nor many of the occupiers. A poll aimed at gauging opinion among the movement’s supporters on the measures was scrapped just three hours before it was due to begin, throwing up more questions about what the next steps for the movement would be.

This leaves many asking the same frustrating question: Where is Hong Kong headed after the occupy movement?

Professor Chan Kin-man, a co-founder of Occupy Central stayed in occupied Admiralty for a month to witness the birth of a self-sustained mass movement initiated by ordinary citizens.

“The ultimate goal of civil disobedience is civic awareness. It’s a significant civic awakening on the part of the public, who have some motivation and autonomy,” Chan says. In the occupied zones, protesters volunteered to prepare food, clean up, replenish daily and medical supplies and decorate their common areas with creative artwork.

Chan believes the occupy movement has changed many things, not just the future direction of social movements, but also the governance of Hong Kong. “(The Government) is neither confronting pan-democrats, founders of Occupy Central nor student leaders. It’s confronting the whole generation,” he says, adding the government should take the initiative and show sincerity by negotiating with democratic forces, otherwise the mass movement will only escalate as protesters try to build up more bargaining power. “We have exploited all the mild strategies … People have already occupied the roads. What else can you expect? A revolution?”

Occupy Central co-founders have said repeatedly, Hong Kong is in an era of civil disobedience. As Chan wrote in his blog, instead of a single protest or petition, recent events mark the birth of a new generation for which, a changed mindset is needed to fight for the space to live under authority’s rule. According to this view, defying the law can be a way to challenge structural injustice, but some fear confrontation will only create a more divided society.