Yu Wai-ying, a self-proclaimed “recalcitrant” journalist at a non-mainstream traditional newspaper thinks professionalism is an important component of a civil society. Yu himself insists on balanced reporting and says professional opinions from scholars and various interest groups can help encourage debate on government policies. Yet he believes that fewer than 10 per cent of the scholars and intellectuals in Macau are willing to do this.

“Owing to the absence of professional advice and university scholars, it is hard for civil society to flourish,” says Yu.

Academic freedom in Macau has been hit hard by the ousting of an academic and a secondary school teacher, reportedly over their links to pro-democratic causes. Bill Chou Kwok-ping, a former associate professor at the University of Macau, was suspended from work after a university investigation ruled he had tried to impose his political beliefs on students, failed to provide different perspectives in class and discriminated against students. The university then refused to renew his contract. Chou said he was not told why, but he believes it was a result of his political stance.

Feeling pessimistic about intellectual freedom in the city, Chou says “depoliticisation” is ubiquitous in Macau, and discussion on political topics like freedom and electoral reforms with students is sort of a taboo. “The repression in Macau is far worse than in Hong Kong. At least no scholars have been sacked [due to their political participation] in Hong Kong,” says Chou.

Kam Sut-leng, who is in her 30s, is a teacher and a social activist with the group Macau Youth Dynamics. She was suddenly dismissed from her job last year by Sacred Heart Canossian College (English Section) without any valid explanation. The school refused to comment on the incident when Varsity made enquiries.

Kam says primary and secondary schools in Macau seldom touch upon politics. Although “Civic Education” is included in the curriculum, the course syllabus does not touch upon constitutional development or civil rights. But, as a teacher, Kam feels she has a responsibility to inspire her students to care more about society.

Although most Macau students are not so engaged in social issues, there are some who break free from the rigid education system to participate in social movements, such as Bosco Wong Kin-long, a year one student from Macau studying government and public administration at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

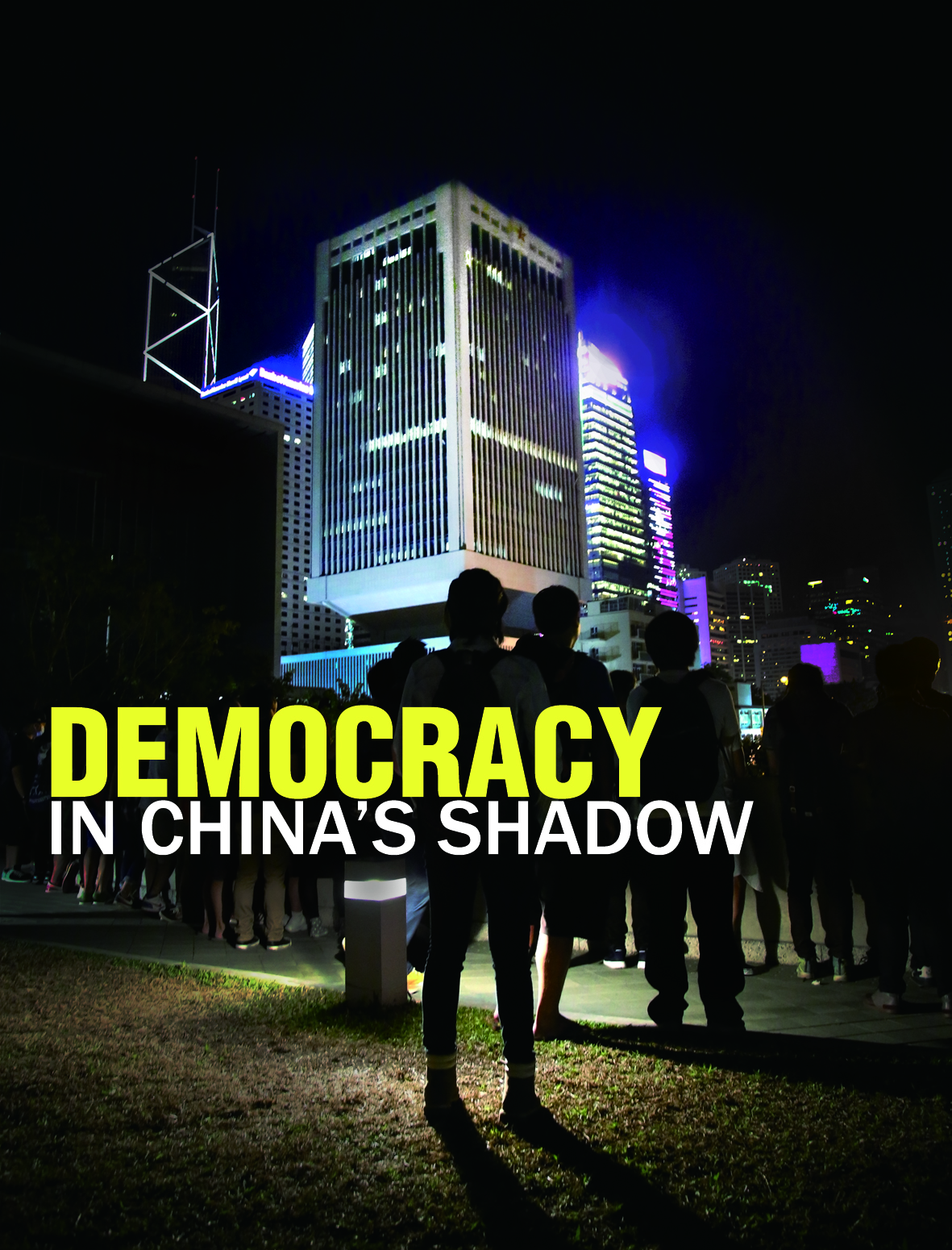

Wong considers his stay in Hong Kong to be a mission to gain experience in the development of civil society. And he managed to experience a civil disobedience movement personally when he joined the tens of thousands of Occupy Hong Kong protesters.

”I am touched by how Hong Kong people voluntarily take to the streets to strive for their own rights, with the whole movement being so disciplined and orderly,” Wong says.

Kam sees this Occupy movement as a lesson in civic education which provides Macau people with the opportunity to reflect on the situation in their city by looking at what is happening in Hong Kong. ”If we Macau citizens see that Hong Kong cannot have genuine universal suffrage, we can imagine that it would be hard for us to have it.”

Even as Hongkongers ponder the path they will take on the road towards achieving greater democracy, their cousins across the water in Macau will be watching closely and taking notes.

Edited by Katrina Lee