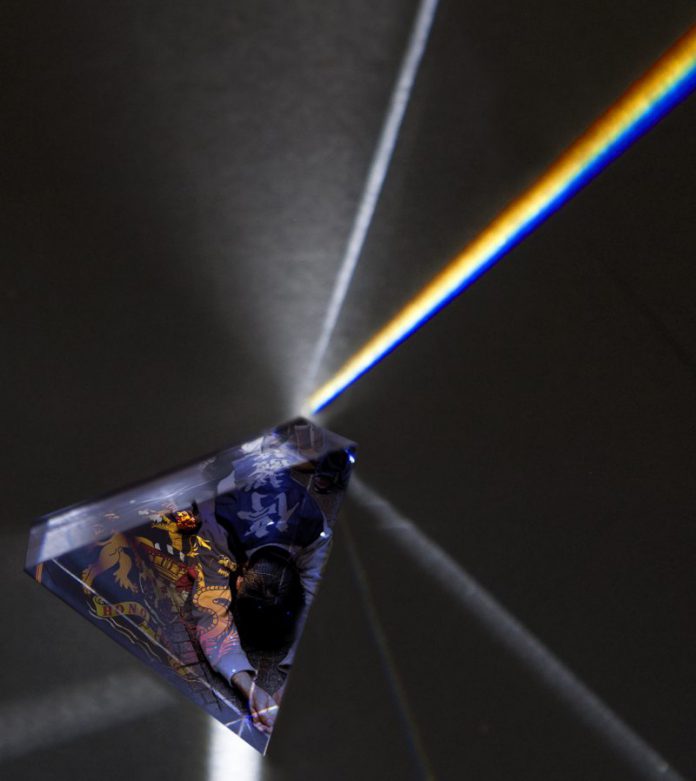

Localisms Across the Spectrum

Without a doubt, the most eye-catching news of September’s Legislative Council election was the victory of six young non-establishment lawmakers who are not from the pan-democratic camp. Local and international media have broadly described them as “localists” (本土派). Today, most people think of “localists” as those who advocate a separate Hong Kong identity and who have an antagonistic attitude towards the Mainland and Mainlanders.

But it is perhaps misleading to think of localism as a single, unified ideology or movement. Scholars say political localism is split between left and right. Those on the left strive for self-determination through peaceful and rational means, while those on the right want to promote Hong Kong nationalism and support radical protests against Mainlanders. This is why we think it might be meaningful to think about “localisms” instead.

In order to understand these differing values, we listen to pro-independence localists such as Chan Ho-tin from Hong Kong National Party and democratic self-determination advocates such as Demosisto’s Joshua Wong Chi-fung.

While the spotlight is on the new political stars, many seem to have forgotten the roots of localism. Professor Law Wing-sang says the first wave of localism appeared in the 1970s, when a generation of Hongkongers born and raised locally began to express their affection for Hong Kong culture and attachment to the city. This developed into a sense of the need to preserve the city’s way of life and values in the years leading up to the handover.

After the handover, discussions about localism emerged from the protests against the demolition of Star Ferry Pier and Queen’s Pier in Central, which were led mostly by the post-’80s generation of activists. The localism of the time focused on preserving Hong Kong’s unique heritage and the collective memories attached to it. It was also concerned with people’s relationship with the land and the plight of the disadvantaged.

To look at how localism, or localisms, have evolved from this to a movement that wants to separate Hong Kong from the Mainland, and even seeks to build a separate nation, we interview some of the activists who participated in the earlier social movements and ask them what they think of localism today.

Localism has become a hot topic among young people who are now more aware of political issues than ever. Yet, some have observed that they seem to have a narrower understanding of what localism means, and have a more hostile attitude towards Mainlanders.

The Occupy Movement in 2014 – which was sparked by Beijing’s refusal to allow a free and open nomination process for the election of the Chief Executive – is said to have “awakened” local youngsters. But Hong Kong-Mainland tensions have been simmering for the past few years, fuelled by such issues as the competition for infant milk powder and maternity ward beds, and parallel traders. These have also shaped the new form of localism.

Polling more than 500 young people as well as talking to concern groups established by secondary school students, Varsity looks into youngsters’ understanding of different localist groups and the rate of their support for localism.

Localism has changed the political landscape but it is not unified and unchanging. In this 2016 November issue, we try to look at how localisms have evolved and how young people view localism today. Our reporters and editors have put in a lot of effort to produce this issue. I sincerely hope you enjoy your read.

Editor-in-Chief

Vivienne Tsang