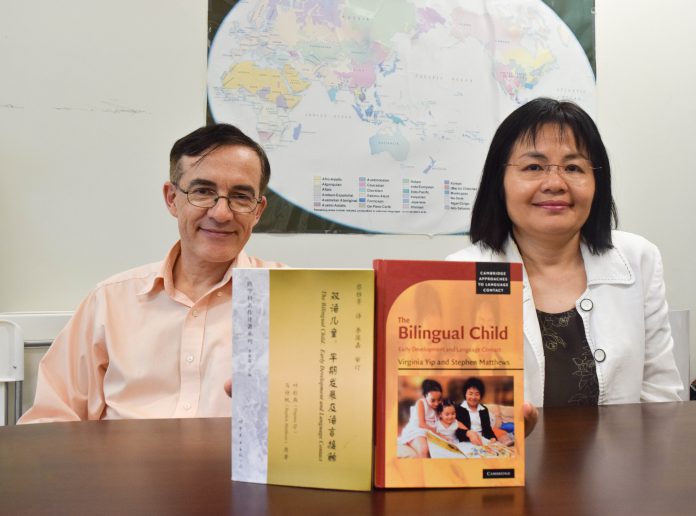

Linguists Virginia Yip and Stephen Matthews blaze a trail in Cantonese and bilingualism studies at work and at home

By Elaine Ng

W

hen Hongkonger Virginia Yip and Englishman Stephen Matthews met at graduate school in the United States 30 years ago, they could not have imagined they would go on to achieve so much together as partners in life. They have become renowned linguists, raised three multilingual children in Hong Kong and co-authored award-winning books. Today, the 55-year-old Yip is a professor of linguistics at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, and her 54-year-old husband teaches linguistics at the University of Hong Kong.

Yip and Matthews are the only local linguists to be awarded the Leonard Bloomfield Book Award in 2009, for their co-authored 2007 book The Bilingual Child: Early Development and Language Contact. The award from the Linguistic Society of America is regarded as the Academy Awards among linguists. It was published 13 years after their first co-authored book Cantonese: A Comprehensive Grammar. Published in 1994, this was the first-ever Cantonese grammar book written in English, and has since been translated into Japanese. The book became the go-to reference for many foreigners who want to learn Cantonese.

Before they met, the couple developed their desire to understand languages differently. Yip’s passion for linguistics blossomed when she studied the subject as an undergraduate at the University of Texas at Austin, whereas Matthews recalls being fascinated by how languages function from around the age of eight. Despite growing up in a mostly monolingual environment, he remembers keeping a tiny “dictionary” where he would collect words and numbers in different languages. This childhood habit paved the way to his studying for a degree in Modern and Medieval Languages at Cambridge University.

Their paths converged at the University of Southern California, where Matthews and Yip both studied for their PhD in linguistics. The young Briton tried to learn Cantonese, which he had barely encountered until the age of 26, both to impress Yip and out of his own interest. At first, he struggled with the segmentation and tones of Cantonese words, but Yip guided him through the process by being as encouraging as she could.

“Cantonese speakers seem to appreciate foreigners speaking Cantonese however badly,” says Matthews, recalling how his then girlfriend never picked holes in the flawed Cantonese he spoke and always appreciated his efforts.

After they completed their doctorate degrees, Yip and Matthews moved to Hong Kong, Yip’s hometown, and they married in 1990. They did not have a specific plan for how long they would stay, and were just testing the waters to see how things would pan out. It turned out to be the right decision. Looking back, the two unequi-vocally describe it as a “big blessing” to have stayed and embarked on their academic careers in Hong Kong.

It all started with their observation that there was a research gap in the study of Cantonese. As Matthews continued to devote himself to learning the language after arriving in Hong Kong, he was shocked and disappointed at the lack of Cantonese learning materials in English, particularly those about grammar. He could see how this would make it hard for foreigners who wanted to delve deeper into Cantonese beyond memorising phrases.

“The way it seemed to me was that, whatever I wrote about Cantonese would be new to the English-speaking world,” Matthews says.

He was right. The book, Cantonese: A Comprehensive Grammar, combined Yip’s expertise in Cantonese grammar and the notes Matthews’ jotted down while watching movies or speaking with his wife in everyday life. It was hailed as comprehensive and down-to-earth and its success motivated the couple to stay in Hong Kong to explore further possibilities of research on Cantonese.

While working on the first book, the couple had observed another gap in the field. Their first child Timmy was born in 1993 and they realised there was little available literature on language acquisition of bilingual children involving a non-European language. After Timmy’s birth, followed by those of their daughters Sophie and Alicia, Yip began to develop a research interest in bilingual acquisition.

Yip and Matthews decided to experiment with the one-parent-one-language approach on their own children, with the mother speaking only Cantonese and the father English at home. “We were going to have children, and they were going to be exposed to both Cantonese and English anyway, so why not?” says Yip as she explains how they initiated the Hong Kong Bilingual Child Language Corpus, which contains longitudinal speech data of her three children and another three who were exposed to Cantonese and English from birth.

The parents started with recording and transcribing what their children said. After documenting the way they acquired English and Cantonese simultaneously throughout their childhood, Yip and Matthews published their monograph The Bilingual Child: Early Development and Language Contact in 2007, which went on to win the prestigious Leonard Bloomfield Book Award.

Matthews describes their three children as having “the best of both worlds”, being raised by an English father alongside a Chinese mother. Yip still finds it amazing that their kids, when immersed in cultures of both sides, had the innate ability to differentiate between different cultural practices and apply them in the right contexts. For instance, they would call their grandparents from the father’s side by their first names, while sticking to greeting Yip’s parents as “gongong, popo” (公公婆婆), or grandma and grandpa in Chinese.

To further expose Timmy, Sophie and Alicia to other languages, the couple is also keen on bringing them to different countries. “If we expose the children to different cultures and different countries, in a way it’s expanding their worldview,” says Yip.

Although the children seemed to effortlessly pick up on how to navigate cultural differences, it took the adults a while to get used to each other’s way of living. Ever the Englishman, it used to bother Matthews that his wife would “order” him to do things without saying “could you?” or “would you mind?”, the polite way to request help in English.

“I think in a lot of cross-cultural marriages, couples have to clarify things all the time to avoid miscommunication,” Yip says, recalling how she explained to her husband that the use of imperatives is not meant to be impolite in Cantonese, eventually resolving the dispute.

Being partners both at work and at home, it is inevitable for that the pair will get into arguments of this kind and worse. However, they both regard mutual respect as the basis of their relationship. “We respect each other as scholars, and we tend to respect each other in other ways as well…then the disagreement is limited by the fact that we respect each other,” says Matthews. As Yip and Matthews gradually learned to embrace their respective cultural attributes, they began to turn their differences into complementary strengths.

These strengths helped them to set up the Childhood Bilingual Research Centre in 2008 at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Yip’s specialty is language acquisition, whereas Matthews’ is the structure and comparison of languages. Putting their two areas of expertise together, they draw on different approaches in their analysis and study of childhood bilingualism. “Some areas are his expertise and some are mine; together we attain synergy,” says Yip.

Speaking of the development of Cantonese over recent years, the couple is deeply concerned about how the language is being undervalued by some families and society at large. They have noticed that more and more Cantonese-speaking parents are allowing their children to learn only English or Mandarin, and choosing to sacrifice Cantonese. Yip and Matthews see the one-parent-one-language experiment on their own children as a demonstration of how parents can have it both ways instead of giving up Cantonese. “Cantonese is a vulnerable language, at risk of becoming endangered; the symptom of that is that not all families are transmitting it to their children,” Matthews says.

Yip and Matthews consider themselves to be contributing to, respecting and maintaining Cantonese. Matthews, who learnt the language through watching Hong Kong films and listening to Cantopop, says he finds it particularly sad to witness Cantonese and the culture that goes with it disappearing bit by bit. Meanwhile, Yip finds it ironic and maddening that foreigners like Matthews and many overseas Chinese families who really make an effort to learn Cantonese, seem to cherish the language more than locals do.

Yip stresses that it is only through transmitting Cantonese from generation to generation that the language will continue to exist. She hopes that the public can see the value of Cantonese as a heritage that is worth passing on. “The vitality of a language is determined by the number of children who acquire it as a first language; when fewer and fewer people speak the language as their mother tongue, its future remains questionable,” says Yip.

Edited by Stanley Lam