Solar energy in Hong Kong still has a long way to go

By Johanna Chan & Scarlet Shiu

Village house owner Newman Lau Man-choi, who is also the president of Sheung Yeung Village Affairs Committee in Clear Water Bay, is finally planning to install solar panels at his home amid measures from the government and Hong Kong’s two power companies to encourage green energy.

But he does still have a few residual worries about the whole process of buying the panels and selling the power generated back to his electricity supplier.

CLP Power Hong Kong Limited (CLP) introduced the Feed-in Tariff (FiT) scheme to purchase renewable energy from energy producers such as local households, private companies, NGOs and schools in October. The Hong Kong Electric Company (HK Electric) will roll out the same scheme for Hong Kong Island and Lamma Island in January 2019.

The FiT scheme is open to customers of the two power companies who install solar or wind renewable energy systems at their premises with a generating capacity of up to 1MW. The power companies purchase electricity produced by an approved renewable energy system at HK$3 to HK$5 per unit.

So far, so good but it does involve money and red tape. FiT does not pay for solar panel installation or maintenance directly. Potential producers, who want to join the FiT scheme but have not installed panels, need to submit a proposal and application forms to their electricity supplier and the required documents to relative government departments. Electric companies and the government will then decide if the potential producers qualify.

Once they are approved, the producers need to contact contractors themselves and purchase the panels. The FiT scheme will buy electricity from the producers after they install all the equipment and the idea is that – money they earn can be used to cover the cost of installation and future maintenance.

Since all the power produced by these solar systems will be fed directly into the FiT scheme. Households will still need to pay their electric bills in the usual way.

The government also pledges to promote the development of renewable energy by relaxing restrictions on the installation of solar photovoltaic (PV) systems on the rooftops of village houses in the New Territories. A new programme to assist schools and NGOs in installing small-scale energy systems will also be launched, according to the Policy Address 2018.

Lau first thought of using renewable energy 10 years ago but only seriously considered it after the FiT scheme was introduced. However, he still thinks more should be done to make the economic incentives more appealing for participants. “The government should also relax a regulation which restricts village house owners to use no more than half of the rooftop area for solar panels installation.” He adds that the current restriction reduces the potential economic benefits for power energy producers.

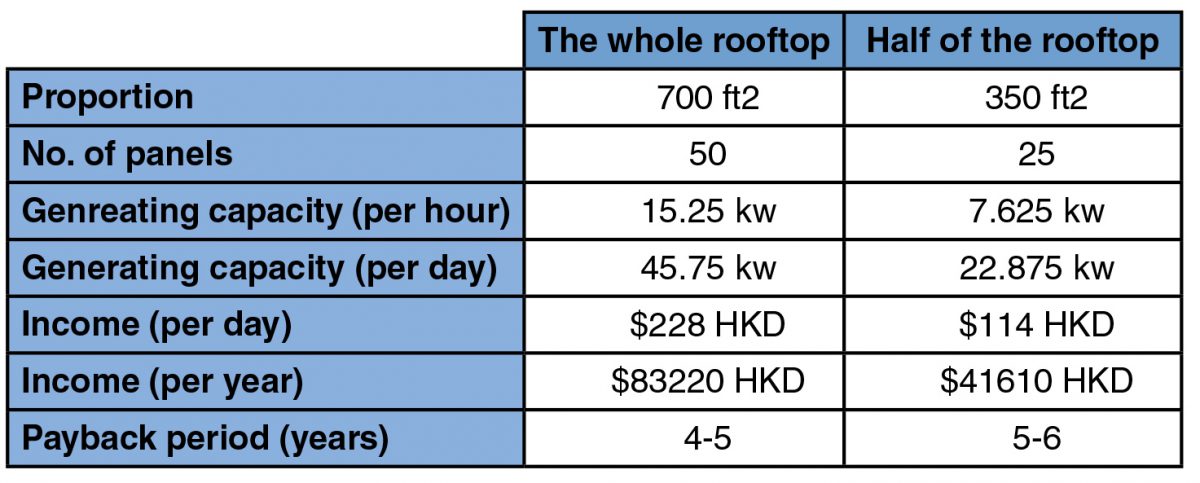

At current prices, Lau has to pay more than HK$200,000 to purchase and install solar panels. His village house rooftop is the standard 700 sq ft, but since it is only legal to use up to half of the rooftop, Lau now can only install a maximum of 25 solar panels. As each panel generates 305W of electricity every effective sunshine hour, the capacity of his renewable power system, consisting of 25 panels, will be 7.625kW.

Hong Kong has a daily maximum of four and a half effective sunshine hours with an average value of three. As all the electricity produced will be fed into the FiT system, and the capacity of Lau’s system is under 10kw, the price of the electricity to be bought will be $5 per unit. The income for Lau, with his roof half filled with panels, will be $114 per day and $41,610 per year with a payback period of five to six years.

“Maybe the government should consider using its discretion over property owners who install solar panels so that we can make full use of the rooftop area.”

However, if as a village house owner, he was allowed to use his whole rooftop, the income for Lau would double to HK$83,220 a year. Even though more panels means more expense, the payback period would still be shorter at around four to five years. The corollary to that of course is that if the government relaxes the regulations on rooftop usage, the financial income will be much more attractive for potential renewable energy producers.

Apart from the building regulations, Lau is also worried that the supporting structure of a solar energy system might be mistaken for an illegal structure.

“Anything placed on the roof might be regarded as an unauthorised building structure. Maybe the government should consider using its discretion over property owners who install solar panels so that we can make full use of the rooftop area,” he says.

Source: Newman Lau Man-choi

Greenpeace campaigner Walton Li Yat-sun shares Lau’s view and urges the government to introduce more supporting measures.

According to the group’s study with the Baptist University and the City University of Hong Kong on the development of solar energy systems in 22 primary and secondary schools this year, many schools are troubled by the initial set-up cost.

“If they do not have enough money or they fail to apply for the Environment and Conservation Fund (ECF), it is impossible for them to take part in the FiT scheme,” he says.

Li points out that even if a school is financially prepared to set up a solar energy system, the complicated procedures and technical skills required in setting up such system can be big challenges. A school might have to seek approvals concerning the installation of a renewable energy system and other supporting structures from different government departments, he says.

“School management might have to deal with numerous government departments simultaneously. An application for approval might take a year or up to six years. This [setting up of a solar energy system] consumes a lot of time, resources and manpower,” he says.

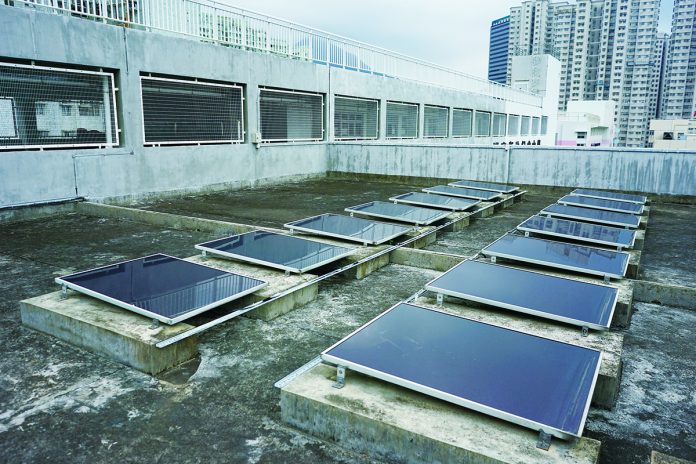

Lingnan Hang Yee Memorial Secondary School is one of the few schools to have had a solar energy system installed successfully before the introduction of the FiT scheme. It took the school three years to complete the installation in 2013.

The electricity the school produces is transferred directly to the school’s own electric system but, as the panels can only generate 5000kWh electricity per year, the renewable energy counts for a very small percentage of the school’s energy usage. On the plus side, the main purpose of the solar system is for education and the installation cost was covered by the Environment and Conservation Fund.

Now the school is planning to join the FiT scheme. If its application to join the scheme is approved, the school plans to use the income it generates to cover the maintenance costs of the solar system and buy better and more efficient panels.

Kwong Shing-hymn, the head of the Moral, Civic and Environmental Education Team, says they were required to submit written reports to the government every month to keep them informed about the progress even after the system was completed. The preparation and submissions were very time-consuming.

“We really need help from the government for expert knowledge and information about solar panels available in the market.”

“It would be better if the procedure could be simplified as the paperwork correspondence with government departments can last for almost two years,” he says.

Other than that, Kwong thinks a lack of adequate technical support from the government was the biggest challenge encountered by the school at the development stage.

“It is difficult for teachers to communicate with an engineer because they don’t have the technical knowledge. For instance, a school might not be aware sunlight reflected by solar panels may cause nuisance to buildings nearby unless they learn about it from professional engineers,” Kwong says.

Kwong explains his school relied heavily on engineering companies for professional advice concerning where solar panels should be installed at the school and which solar panels should be purchased in order to achieve the best result. At the same time, he worries that schools might be cheated by engineering companies which can play on their ignorance to make money.

“We really need help from the government for expert knowledge and information about solar panels available in the market. This [technical support] has always been insufficient. No one has ever told us which solar panel is good or whether it is reasonably priced or if certain panels have defects. We never get that support,” he says.

Dr William Yu Yuen-ping, the founder and chief executive officer of World Green Organisation, which helps organisations and schools find qualified engineers and professionals to help them with installations, understands Kwong’s worries.

“The purpose of FiT is to set an example by exploring renewable energy by attracting individual producers with financial benefits. We are not able to replace Hong Kong’s power resource on a large scale right now,” Yu says.

He adds that one of the greatest concerns is the lack of talent in the industry, as the sector is growing fast. He says some operators offer to install solar panels at a low price but the quality of these panels is very poor and they do not offer a long-term maintenance service. “A good quality solar panel has a life expectancy of more than 20 years, but low-quality panels can only last for about a year or two,” he says.

Apart from providing support to schools, Yu’s organisation is also promoting renewable energy in 150 secondary schools by conducting eco-tours and workshops. He believes it is important to educate students about the importance of using renewable energy and how solar energy systems operate in their schools.

“I think it is important to engage students in learning the theories and knowledge behind the systems and then pass on the message of leading a low-carbon lifestyle to them,” he says.

Photo courtesy of Lingnan Hang Yee Memorial Secondary School

Edited by Grace Liyang