The city’s irreplaceable post-war architecture is being overlooked, conservation activists claim

By Jasmine Ling & Valerie Wan

Built in 1951, PMQ, the former Police Married Quarters on Hollywood Road, is now a Hong Kong creative industry landmark. Back in the 19th century, the site was the original home of the Central School, which nurtured many famous figures including Sun Yat-sen who studied there in 1884.

But the history and all the tales about PMQ would have been lost if Katty Law Ngar-ning, who founded the Central and Western Concern Group, had not taken action to urge the government to conserve the building 13 years ago.

In 2005, the concern group campaigned to conserve PMQ after learning the building was on the list of sites for sale. “The original land use was GIC [government, institution or community], but then we found out that it had been changed to high-density residential land use in around 1997 to 1998 and would be auctioned in 2015,” she says.

Law, who grew up in the neighbourhood, has always thought PMQ and other structures around it form a cluster of buildings with a rich historic value. The architectural features of PMQ, which highlight simplicity in design and use of space, are representative of the unique style of buildings constructed in the 1950s in Hong Kong.

After learning that the building site was up for auction, the group conducted research and spoke at public consultations. Two planning applications filed with the Town Planning Board were also made in an effort to conserve the site for community and recreational use. The board rejected them. “Why did the government want to sell the precious site to developers for luxurious property projects?” she says. “Even though it is not a colonial building aged over 100 years, it was built in the 1950s and has its own unique value in contemporary architectural history.”

The government’s change of heart came in 2007. PMQ was removed from the List of Sites for Sale by Application and the Development Bureau announced PMQ would be transformed into a creative industry landmark in 2010.

Law criticises the government for ignoring the importance of conserving cultural heritage, especially 1950s’ buildings, such as PMQ, Government Hill, and Central Market. “From the government’s view, ancient heritage is always valued over relatively modern heritage,” she says, “but if they keep on removing the modern ones, it will lead to a gap in Hong Kong’s [architectural] history.”

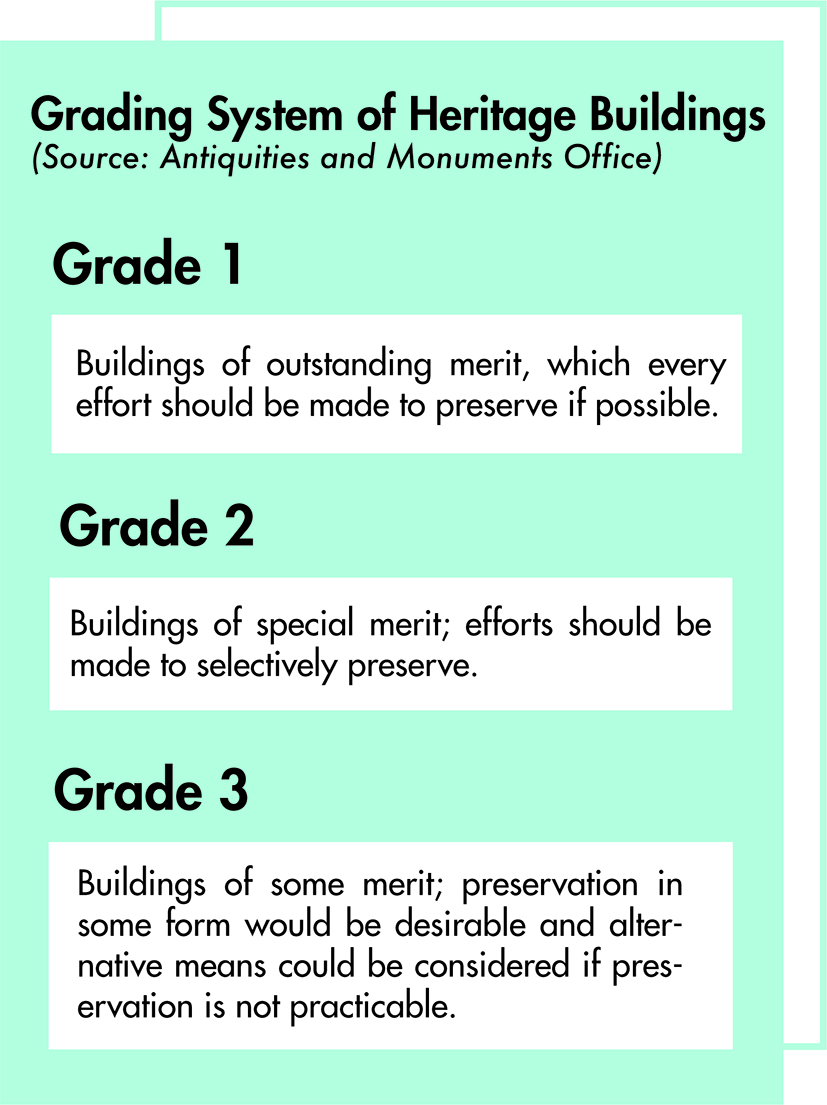

State Theatre (formerly known as Empire Theatre) in North Point is another example of post-war modernist architecture that has survived threats of redevelopment. Featuring a series of concrete arches over its roof, the theatre was built in 1952 and served as a world-class performance venue. Concerns were raised over the building in 2015 amid fears the theatre might be demolished for redevelopment. In April 2016, the Antiquities and Monuments Office (AMO) listed State Theatre as a Grade 3 building, meaning the building could still be torn down for development.

Paul Chan Chi-yuen, co-founder and chief executive officer of commercial cultural enterprise Walk in Hong Kong which promotes local culture by organising sight-seeing tours, campaigned for the preservation of the theatre. He criticised the grading system for lacking transparency. “Even till now, we still don’t know how the Grade 3 decision was made in the system,” he says.

Since March 2009, The AMO has been assessing and grading 1,444 historic buildings into three levels or nil grade status according to their historic value. As of September 2018, among the 1,421 historic buildings with confirmed grading, 17 were built between 1940 and 1945, and 280 were built after 1945. In a written reply to Varsity’s enquiries, the Development Bureau states that “while the prevailing grading assessment focuses on buildings mainly built before 1950, buildings built after that year have also been assessed on cogent need and on a case-by-case basis”.

The six assessment components are historical interest, architectural merit, group value, social value and local interest, authenticity, and rarity. A panel of four experts comprising of historians and members of the Hong Kong Institute of Architects, Hong Kong Institute of Planners and Hong Kong Institute of Engineers is responsible for the assessment. The Development Bureau says that the grading system for historic buildings, which is administrative in nature, aims to provide an objective basis for assessing the heritage value of historic buildings in Hong Kong, and hence their preservation need.

Chan recalls the expert panel citing the building’s loss of authenticity due to interior modifications as the major reason for the grading. Yet, the panel admitted the argument was based on assumptions without detailed investigation. Chan criticises the AMO for failing to recognise the heritage value of the theatre which was built by Harry Oscar Odell, one of the most significant figures in the Hong Kong entertainment history. Odell devoted his life to building the world-class theatre in which the late British tenor Peter Pears, Katherine Dunham’s Broadway dance company and the late Taiwanese pop singer Teresa Teng once performed.

Despite its glamourous history, some panel members argued the State Theatre had a fairly short history. “The point is if you don’t preserve a 60-year-old building now, it will never turn 100 years old. You can’t demolish the building just because it is still young now,” Chan argues. He also condemns the grading process as a “black-box operation” which relies heavily on the subjective opinions of panel members. “How can the process which controls the fate of many precious historic buildings be so outdated and feudalistic?” he says.

Chan and his team conducted research and gathered solid evidence in a bid to overturn the grading result. They organised a campaign to arouse public concern for the case and persuaded concerned property owners to preserve and revitalise the theatre for the benefit of Hong Kong.

Chan’s efforts paid off and, in 2017, State Theatre was upgraded to a Grade 1 historic building. However, unlike declared historical monuments, Grade 1 building owners are free to modify, demolish, or conserve their properties as they wish. In October 2018, New World Development, which was considering to start a conservation project for the first time, applied to the Lands Tribunal for a compulsory sale order regarding the State Theatre Building.

Financial resources are another major consideration for conserving historical buildings. In 2008, the government set up the Financial Assistance for Maintenance Scheme on Built Heritage, for private owners of graded historic buildings. The ceiling of the grant for each successful application is HK$2 million inclusive of both the consultancy fee and the costs of the maintenance work, and the payment will be made on a reimbursement basis.

The third-generation owner of the Yuen’s Mansion in Mui Wo, Yuen Chit-chi, says he wants to preserve the family mansion which was built in the 1930s but the government does not provide comprehensive assistance to private property owners. The fortified estate consists of six Grade 2 historic buildings: the main house, two watchtowers, two ancillary houses and a barn.

Town planner Stanley Ng Wing-fai has followed Yuen’s case closely. He says the Maintenance Scheme is not applicable to compound buildings like the Yuen’s Mansion. “The scheme requires applicants to pay first then receive reimbursement afterwards. And many owners cannot afford the initial payment,” he says.

The F11 Foto Museum in Happy Valley, a Grade 3 historic building, has a totally different story to the sad tale of Yuen’s Mansion. Douglas So Cheung-tak, a solicitor and a photography and heritage enthusiast, bought 11 Yuk Sau Street for HK$90 million in 2012 and founded the museum two years later. It remains an example of how historic buildings in Hong Kong can be privately revitalised and renovated – in this instance at a cost of over HK$10 million. The owner is also committed to the long-term maintenance of the building.

Fiona Li Yuen-kwan, manager of F11 Foto Museum and former assistant curator at the Antiquities and Monuments Office, says the case of F11 might be one of a kind, as not many owners have both the passion and the resources to conserve a historic building. “The most difficult part isn’t the one-off payment, but the continuous maintenance of the building,” she says.

Referring to her experience at the AMO, she says conservation policy in Hong Kong is quite short-sighted and the role of the government is relatively passive. “They only handle problems when it becomes urgent and controversial,” says Li. In her opinion, education is essential to arouse public awareness about the importance of conservation.

Li Ho-yin, associate professor and head of the Division of Architectural Conservation Programmes at the University of Hong Kong, says the grading system in Hong Kong is outdated. The conservation concepts the government adopts lag far behind countries like the UK, Singapore and China. “When people say ‘striking a balance’ between conservation and development, they are assuming the two are in conflict,” says Li. “Conservation should be an important component in sustainable development.”

Edited by Marilyn Ma