Scavengers strive to make a living while escaping from the eyes of the hygiene officers.

By Amelie Yeung

Almost every evening, elderly woman Susan Tang* does her best to flee when uniformed officers from the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department (FEHD) approach.

Scavenging is a risky business as FEHD officers could confiscate her collection on the charges of street obstruction. Tang scavenges on the streets of To Kwa Wan and typically flees from the officers once a day when they patrol the area. If she fails, she will be fined HK$1500.

“I just wish they would leave me alone. I’m only trying to get a few extra bills,” Tang says.

The monthly income of a scavenger is HK$9000 a month, which is lower than that of the minimum wage, according to a 2021 report by Waste Picker Platform, a subsidiary body under the Mission to New Arrivals Limited’s School of Poverty Caring (SPC).

“I mostly collect cardboard and Styrofoam boxes. On a good night, I earn HK$20,” the 77-year-old says. For every kilogram of cardboard she collects, she gets only HK$0.8.

Tang splits her time between scavenging and raising her grandson, so she does not spend as much time scavenging as other full-time scavengers.

Every night at 6 p.m., Tang gets her first round of cardboard from stores such as fruit and vegetable stalls. The second round comes at 10 p.m. when restaurants close.

Tang piles the scavenged material on her trolley after cutting the boxes and laying them flat. She then wheels her trolley to the alleys, where they remain for the night.

The next day, Tang sells them to recycling businesses after spraying them with water to make them heavier. She finds them hard to transit with added weight, but the water is necessary.

“More weight, more money, even if it hurts my back,” Tang explains.

Being a widow, she takes care of her only grandchild who is in primary one. Her son died a few years ago, leaving behind his wife.

“My daughter-in-law doesn’t care about my grandson or me. She parties all day and never come home,” says Tang.

Unable to qualify for the Comprehensive Social Security Assistance (CSSA) as her assets slightly exceed the limit, Tang and her grandson rely on her savings and her old age allowance, which is HK$1,290 a month.

“I don’t think the savings are enough, not for raising my grandson. So what else can I do but scavenge?” she says.

Citywide Cleanup

This August, the Hong Kong government launched a three-month programme named “Tackling Hygiene Black Spots”. The initiative will clean 600 hygiene black spots in the community to stop waste accumulation and rodent problems.

According to FEHD, its primary concern is the maintenance of environmental hygiene, especially issues aroused by scavenging activities. Enforcement priority is given to cases that obstruct cleansing operations, an offense under section 22(1)(a) of the Public Health and Municipal Services Ordinance (Cap. 132).

FEHD will issue a notice to the owner of the article obstructing the operation to remove it within four hours.

“Enforcing cleanliness on the streets strictly appears to reduce environmental hygiene issues, but in reality, the core problems remain. When enforcements are relaxed, the hygiene issues will return,” says Peter Chiu Yat-fai, Ministry Coordinator of SPC.

“Even if you improve the elderly welfare program or elderly employment, scavengers will still exist because some of them enjoy the flexibilities of the job,” he says.

“Scavengers are accused of causing hygiene issues. For that, they have been driven away, complained about, given a ticket, or even insulted,” he continues.

Waste Picker Platform hopes more people can learn the importance of scavengers to the city.

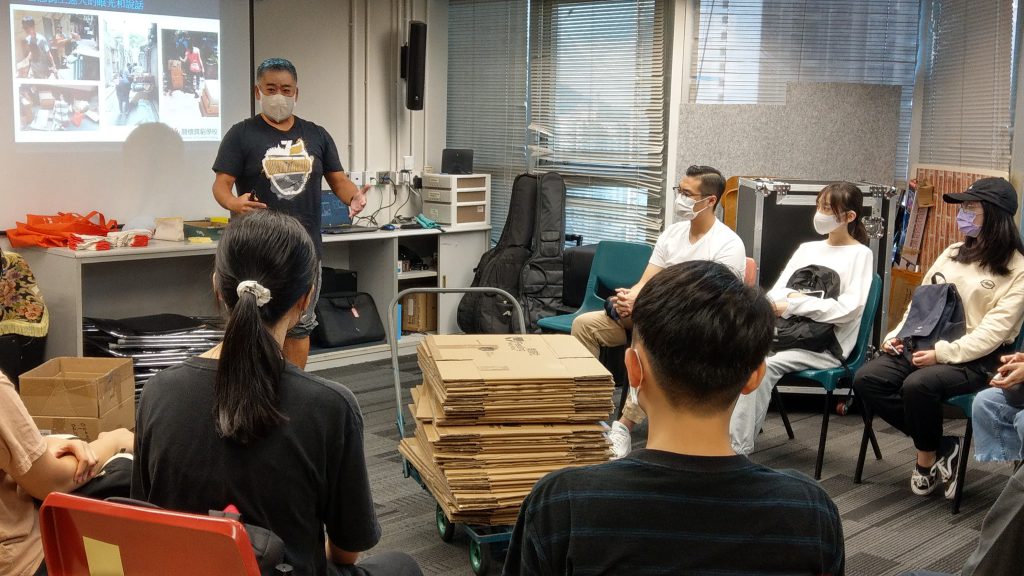

“We host workshops with human libraries so that participants, most of them students, will understand more about scavengers and their contribution towards society,” Chiu says. A human library refers to a person who shares their stories with listeners.

“What scavengers really need is a friendly space for them in the community,” he says.

While Hong Kong is having its citywide cleaning activity, New York City also initiated the “Get Stuff Clean” campaign in November this year. Under the USD14.5 million plan, the government hopes cleaner streets and rodent eradication will improve the quality of life for its citizens.

A Precarious Balance

Waste management is completely necessary, according to Professor Hung Chi-tim at the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care (SPHPC).

The Professor of Practice in Health Services Management asserts that it is important to keep back alleys clean and free from obstruction by removing rubbish that accumulates as soon as possible, even if this clashes with scavengers who often cause hygiene issues.

According to Hung, rubbish can become shelters for pests, as well as posing access issues so these areas must be cleaned up for the sake of cityscape and public health.

“It is very noble that some of the elderly people insist on earning their living all by themselves instead of applying for CSSA. Social enterprises should make use of the productivity of elderly scavengers safely so that they can keep their self-esteem and be able to earn some money of their own,” he says.

His sentiments are echoed by Professor Daisy Zhang Dexing, also from SPDPC.

“The government should have clear regulations on whether the items are disposable and where to place and collect the discarded items. Only in this way can scavengers cooperate with the government’s operation as well as help promote community hygiene,” says Zhang.

“Crucially, the welfare of the scavengers should be taken care of by forming a labour union for the unprotected scavengers to get a regular salary. They should not lose their dignity or be discriminated against,” she says.

*Name changed at the interviewee’s request

Sub-edited by Gloria Chan