“Addictive” online platform interfaces are designed to keep users hooked for hours and hours

By Suan Yeon

University student Chan Myae Kyaw spends five hours a day on average watching YouTube shorts.

“I pick up my phone at 9.30 p.m. and even before I realise, it is already 1.30 a.m. I don’t even feel like it has been four hours. I just sit in the chair and watch YouTube shorts and I am often late for classes,” the 22-year-old student says.

“I just can’t stop. I keep scrolling and scrolling on YouTube Shorts endlessly. Screen time addiction has made me unable to focus. Now I can no longer watch YouTube videos that last for more than three minutes, only shorts,” the Year Three student adds.

“You can see the red bar moving, so you know the next video is coming – so you don’t skip it,” he says. The Biomedical Engineering student recalls having good grades before he got addicted.

“I scored straight As in Year One. Now B is my average grade,” he adds.

According to a research on the association of screen time with brain connectivity conducted by the University of California in 2023, adolescents who spent more than four hours per day on screens had reduced brain connectivity.

These reductions in connectivity were associated with poorer performance on cognitive tasks that measure attention, memory, and decision-making.

After his GPA dropped, Chan Myae Kyaw started to go to the gym in 2024 to cut down screen time.

“I feel sluggish after spending too much time on my phone. But now I realise when I am actively doing something like working in my lab or working out, my screen time decreases,” the Year Three Student says.

A report from Statista in 2023, an online platform specialising in data gathering and visualisation, points out South Koreans spent an average of 44.89 hours a month on YouTube’s mobile app.

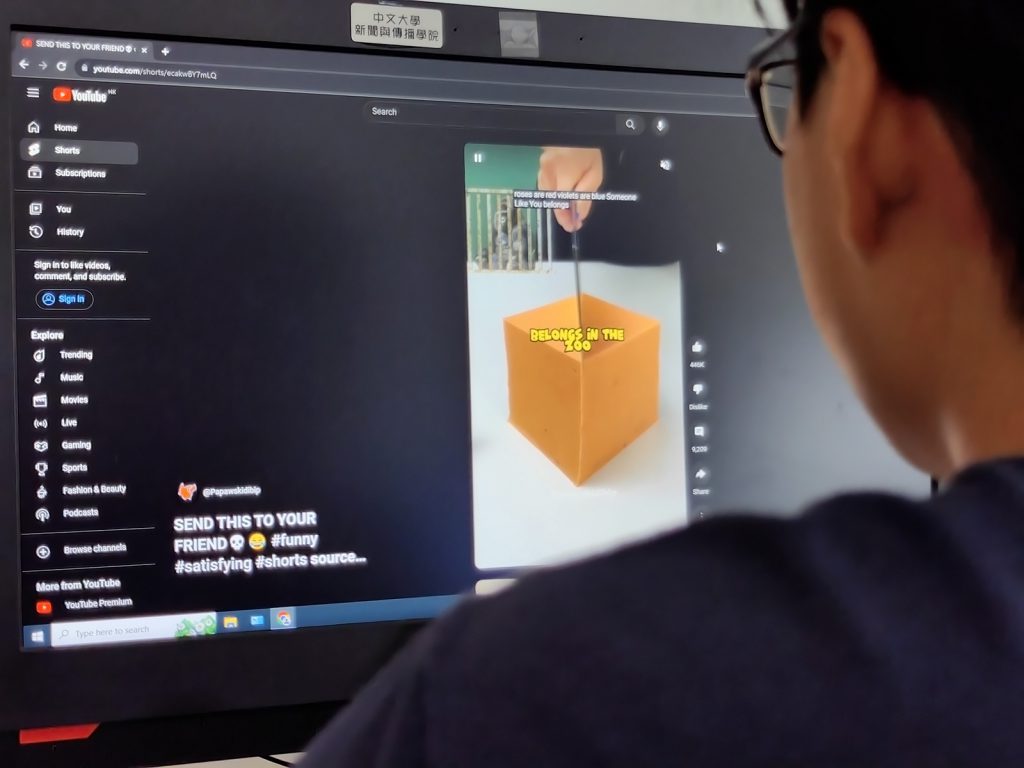

Assistant Professor Yang Tian, from the School of Journalism and Communication at the Chinese University of Hong Kong points out that YouTube’s personalisation algorithm makes use of users’ previous experiences and data to predict what they might like.

“Personalisation algorithms facilitate users’ flow status so that people are fully immersed in the environment and cannot feel time fly by. The companies want users to spend more time because time is traffic, and this traffic can be turned into advertising revenue – that’s their income,” Yang says.

The social scientist adds that the companies exploit users’ intuitive nature to capture information.

“Users are very reactive to social endorsement. That is why when they see ‘Likes’ or ‘Views’ coming in, they want to look at those numbers, crave for those interactions, and try to look at those clips that go viral online,” he says.

“By conducting thousands of user tests, interface designers can find the so-called “optimal interface” that best serves their interests. Like an interface that keeps people on that page for the longest period,” he adds.

The computational social science professional highlights that technology is not the only thing to blame.

“When we think about addiction, we also have to think about the flip-side of the coin. People may want to use technology to avoid certain things by immersing themselves in a place where they cannot feel the reality. It is always the people who are addicted. It is an interplay between the technology and the user,” Yang says.

In a Netflix documentary, The Social Dilemma, launched in 2020, former Google design ethicist Tristan Harris, explains persuasive design technology.

“Persuasive technology is a sort of design intentionally applied to the extreme, where we really want to modify someone’s behavior. We want them to take this action. We want them to keep doing this with their fingers,” he says.

“We can demand that these products be designed humanely and users not be treated as an extractable resource,” the Centre for Humane Technology founder adds.

Edited by: Ryan Teh

Sub-edited by: Sunnie Wu