The detention of more than 50 writers of gay erotica in mainland China has led to heated debate.

By Della Qing

Out of anger and fear, gay erotica fiction writer who publishes under the pen name Ni Xiaoyu has deleted all her work after learning more than 50 other writers who used to post their stories on Haitang, a fiction website, have been arrested.

“I’m very furious about the arrest. I don’t think writing gay erotica fiction should be outlawed. Our work does not do any harm to anybody,” Ni says.

“I won’t stop writing because I’m a freelancer, and I’m happy to continue writing stories. Those who make a living by writing have to think carefully about what to write, how to write, and where to write. Fear will limit their freedom to create,” the writer adds.

Founded in 2015, Haitang Culture is an online fiction website affiliated with Longma Culture Limited Company in Taiwan. It features gay erotica and other fiction which are only accessible for internet users who are 18 or above.

The hot list of top 15 articles highly recommended by readers on fiction website Haitang. All of them are gay erotica fictions.

“I’m worried about other fiction websites such as Weibo and Lofter that are subject to the authorities’ censorship,” the writer, with ten years of experience writing gay fiction, says.

“Since the censorship in Mainland China is getting stricter and stricter in recent years, Chinese gay erotica writers tend to choose Haitang Culture as an enclave to avoid content censorship, for this website is based in Taiwan where regulations on gay erotica fictions are relatively lenient,” she adds.

Under Chinese law, writers who make more than RMB ¥250,000 (US $34,500) from selling erotic materials can face a maximum sentence of life imprisonment, although in practice they can get shorter prison terms if they settle the penalty.

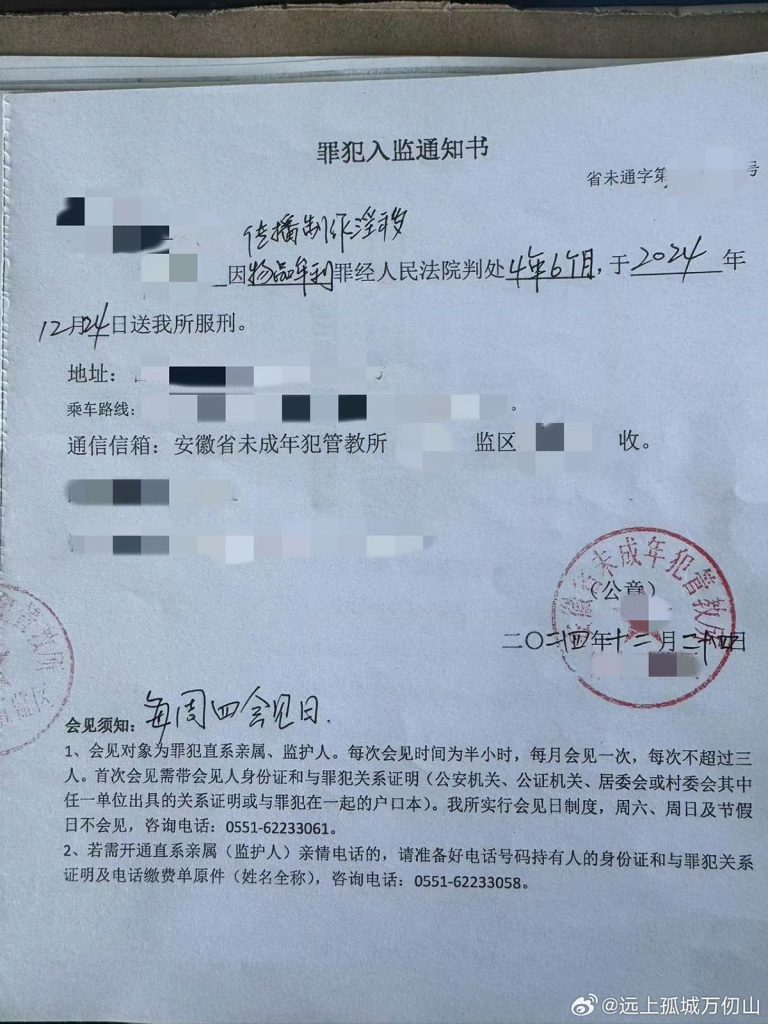

One of the arrested is a top writer who publishes under the pen name Yuan Shang Bai Yun Jian. She was sentenced to four years and six months’ imprisonment with confiscation of her personal property of RMB ¥1,850,000 (US $254,400) and a fine of RMB ¥1,850,000 (US $254,400).

“I think the penalties are certainly overwhelming and the laws should be reviewed. It is ridiculous to discuss laws and penalties when there is no rating system about literary work in mainland China,” Ni adds.

In October 2024, a woman who was believed to be Yuan’s sister posted a message on Weibo, said her sister who has been posting stories for almost a decade under the pen name Yunjian, has gone missing since mid-June 2024 and appealed to readers for donations to settle the penalty.

In early January 2025, a man claiming to be Yunjian’s husband posted on social media that his wife was sentenced to four and a half years in prison and thanked readers for their support.

The post also highlights a message which is believed to be from the writer: “I will work hard in prison and try to get out earlier. By then, I’ll thank my readers in person.”

Another freelance gay erotica writer Shi Xiaoxuan, who also posted her works on Haitang, shares Ni’s frustration and worries.

“I don’t think writing gay erotica fictions is a crime. The only criminal element in these cases may be tax evasion. But I can understand why writers do not declare information from their written work. Writing gay erotica is like working in the grey area in China. If they pay tax, the police will investigate them,” Shi says.

“I think the police in Jixi arrested the gay erotica fiction writers because the government faces financial problems,” she adds.

“I am not surprised with the sentencing of Yunjian. I don’t want to say that things are going backward, but the censorship is indeed getting tighter and tighter. Of course, I hope this kind of thing will not happen to anyone,” Shi says.

Apart from feeling worried about censorship, the two writers also find the fiction website, Haitang Culture, irresponsible for failing to protect writers who contributed work to the site.

“Haitang Culture takes commission from writers, but it does not bear any responsibility for offering legal protection to writers,” Ni says.

“The online fiction site even lied to the writers after the arrests were made, claiming it was safe for them to write on the platform,” Shi sighs.

After the arrest of around 50 gay erotica writers in June 2024, the fiction website only locked all the writers’ columns without any financial or legal assistance to their contributors.

Varsity reporter has emailed questions to Haitang Culture, but no reply has been received before publication.

“I’m not worried about breaking the law because I live and write abroad. But I have a lot of sympathy for authors who write in the same language as me in mainland China,” Shi says.

Professor Fang Kecheng from the School of Journalism and Communication of the Chinese University of Hong Kong points out that the arrests of writers show that censorship is getting stronger in China.

“Usually, politically sensitive issues are more likely to be censored. But in the past decade, censorship of content related to morality has grown stronger too,” Fang says.

“These issues might not be related to politics, but the government thinks they are dangerous, toxic, and influenced by western values, which might challenge the country’s future development and solidarity of the nation,” he adds.

Fang believes writing should be absolutely free, and regulations should be applied to the publication and distribution of written work. “Every country has its publication regulatory system, like a rating system,” Fang says.

“The key is that the regulations should be passed with public consent. The standards and processes of how regulations are applied should be transparent and open to the public. All matters should be discussed and solved in a legal framework,” he adds.

Edited by Bliss Zhu

Sub-edited by Cathleena Zhu