Lax visitor registration is compromising security on public housing estates

By Raven Hui & Sam Kwong

In front of the gate, there is a panel with buttons and a keypad next to a screen displaying the words “Please enter the password”. A security guard stands behind the gate to keep an eye on the people coming in and going out. This is a common set-up for ensuring secure access at most public housing estates across Hong Kong these days.

However, not all residents use the keypads every time – some may find it difficult to remember the passwords as they are regularly changed for security reasons. Often, helpful security guards will open the door or press the lock release for residents’ convenience.

Yet, this seemingly helpful gesture can occasionally allow undesirable strangers to enter the buildings. In an infamous case last June, a man followed a woman to her home in Tuen Mun’s Po Tin Estate before forcing the victim into her own unit and raping her.

Mrs Chan, who didn’t want to give her full name, lives on Po Tin Estate, where some of the units are used for interim housing. She says the security guards in her building usually open doors for people with familiar faces. However, she thinks it is difficult for the guards to remember the faces of all the residents because of the high mobility at the estate, where people tend to come and go.

“It’s actually quite expected that he [the security guard] wouldn’t notice [the suspect in the 2017 rape case] was an outsider, because there’s too much of a mobile population here, because [they] move in and out. Sometimes they [the security guards can] forget, right?” she says.

Mrs Chan recounts an incident in which she saw a man claiming to be looking for somebody entering the lift of the building she lives in. She found it suspicious that every time someone exited the lift, he would try to follow them. Chan says that after the 2017 rape case, she pays more attention to whether the people entering the building are residents or strangers.

Varsity has found that it is a common practice for security guards in public housing estates to open doors for those entering buildings. In February, our reporters tried to get into 65 buildings in nine public housing estates located in Kowloon East, Kowloon West, New Territories North and New Territories South and Hong Kong Island (categorised according to their respective police districts) assuming the identity of private tutors. The reporters managed to enter more than 90 per cent of the buildings by either following residents when they went in or by having the doors opened by security guards.

Security guards questioned us on our identity 20 per cent of the time, and we were required to log our details into the visitors’ registration less than 8 per cent of the time.

To obtain the Security Personnel Permit required in order to work as security personnel, a guard has to pass a trade test recognised by the Security and Guarding Services Industry Authority (SGSIA), have a certain number of years of experience in performing security duties over a specific period of time, or pass the end-of-course exams for security training courses endorsed by SGSIA.

According to the Syllabus for the Trade Test for Security Guards, which is largely based on the basic training standards set by SGSIA, the main duties and responsibilities of a security guard include the prevention of unauthorised access to premises and properties, registration of visitors and taking precautionary measures to prevent personal data from leaking out to unauthorised parties. Guidelines for security guards are also subject to contract requirements between the estate and estate management companies.

Ah Lai (who does not want to disclose her full name to protect her job) is a security guard who sits behind the counter in the lobby in a public housing estate building in Wong Tai Sin. Her main duties are to memorise the faces of the residents, spot visitors and record their identities, and to take turns to patrol around the building. Ah Lai says she only presses the door release button for residents she recognises.

Compared to private residential buildings, public housing tends to have a lot more units. This makes it difficult to remember the faces of all the residents. Ah Lai says that she has to stay alert by constantly looking at the gate, but there is a chance that she may miss a stranger and end up mistakenly letting outsiders enter despite her 13 years of experience as a security guard.

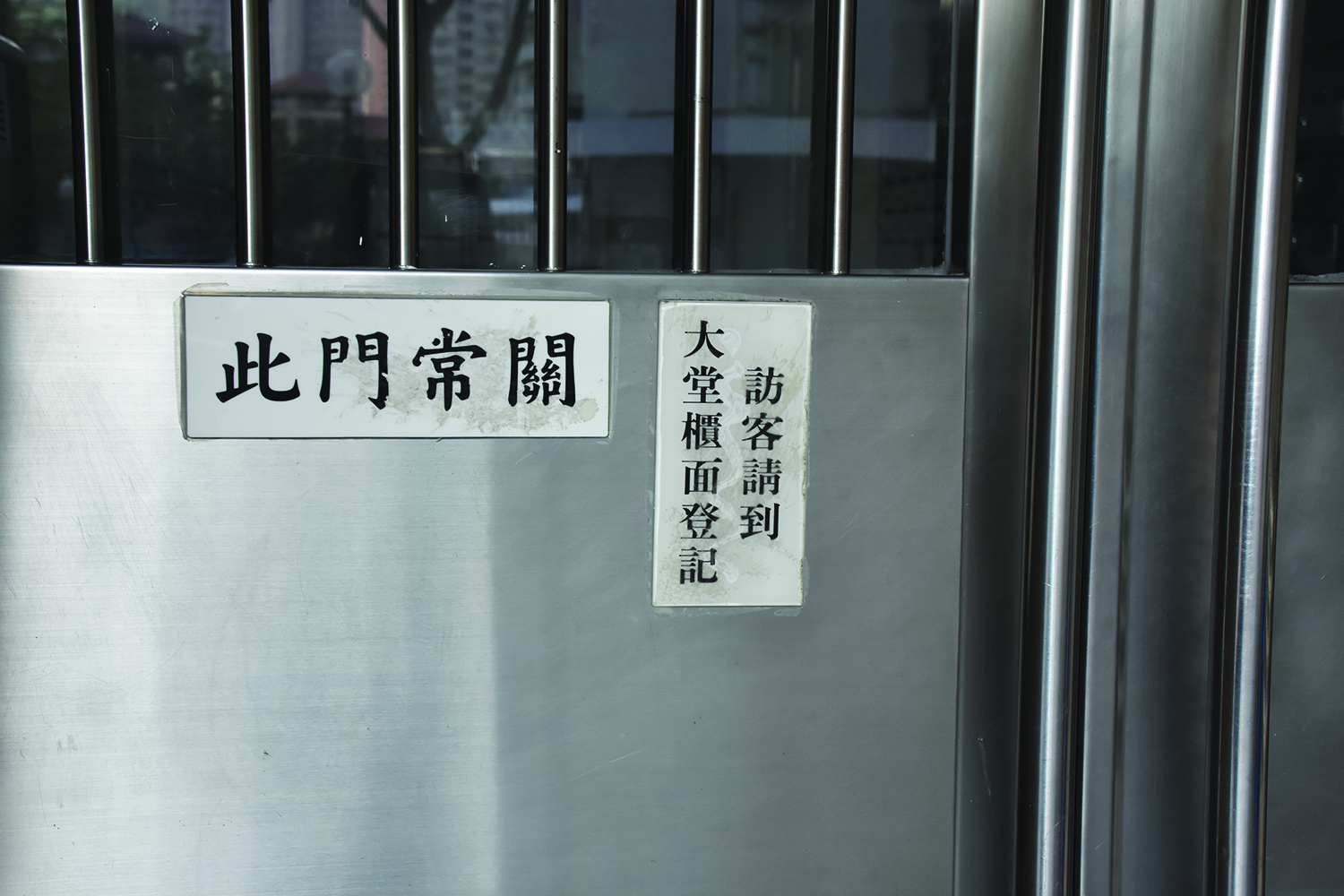

On the ground floor of public housing buildings, there are usually notices reminding visitors to register their details and residents to key in the entrance password themselves for security reasons. Ah Lai says that in principle, residents should enter the password themselves and security guards should only open the door for residents who have mobility problems. She explains that while she does open the door for residents, this is because she has been working in the same building for years and has memorised the faces of most residents.

The 62-year-old says it is hard for her to follow the guidelines strictly because residents are used to having security guards open the door for them and some even take it for granted.

“Sometimes when we can’t open doors because we’re refilling our water bottles or have our heads down writing things, they’ll glare at you… They’ll scold us ‘what are you doing sitting there? Why don’t you open the door?’” Ah Lai says.

Public housing estates used to be seen as hotbeds of crime. In 1986, RTHK’s Hong Kong Connection programme ran an episode on the triad-ridden environment in Kwai Chung Estate. Tsz Wan Shan Estate, which was later subdivided into several estates, was the sphere of influence of a triad group known as the Thirteen Guardians of Tsz Wan Shan (慈雲山十三太保).

With major improvements in security starting in the mid-1990s, public housing estates have gradually shed the negative images from the past. Installations, such as CCTV, entrances with password pads or smart cards, and intercom systems were put in place by 1998. These have improved the security conditions on public housing estates.

Authorities do not provide a breakdown of crimes committed on public housing estates, but from a search of news articles of reported cases in 2017 in the Apple Daily (and accessed via the Wisers Information Portal), we found seven instances of rape by inputting the search terms “estate” and “rape”. Of these, three took place on public housing estates. When the search terms “estate” plus “burglary” were entered, reports involving seven burglary cases came up, one of which took place on a public housing estate.

Hammie Ng Ka Wing has been living in Pak Tin Estate in Shek Kip Mei for eight years. She thinks the estate is safe even though she observes that most residents do not input the password when they come in through the main entrance of her building. The default appears to be security guards opening the door for residents and Ng does not have a problem with it.

“If they [the security guards] can recognise the residents, it’s good [to open doors for them]. This way … the interpersonal relationship can be better. It’s like helping each other out,” says Ng.

However, she thinks there may be a security issue with the building’s back entrance. She herself usually enters the building the back way where there is no security guard and residents must input a password.

“Those doors close very slowly, people can seize the chance to sneak in,” says Ng, who speculates the doors close slowly so as to not cause injury to the elderly. “But this may let criminals sneak in,” she adds.

Ng is aware of the series of burglaries in Kowloon East from July 2016 to October 2017 that targeted public housing estates in Kwun Tong and Sau Mau Ping, but she is not worried this will happen in Pak Tin Estate.

“It’s unavoidable. On the other hand, our estate is rather old, most people are not very wealthy, so the chance [of burglary] will be lower,” she says.

Hui Kam-sing is a Wong Tai Sin district councillor and a member of the Estate Management Advisory Committee of Chuk Yuen (South) Estate. Growing up on a public housing estate in Tsz Wan Shan and having served as a social worker for people affected by public housing redevelopment in the 1980s, he has witnessed how security systems have been standardised and improved in public housing over the years.

But while the hardware has improved, Hui thinks the human factor is what determines the standard of the “software” in security.

“First, it depends on individual security guards, some are more proactive in [in checking identities],” says Hui. “Second, it depends on the demand of the estate management companies or the residents. To be honest, residents in public housing don’t necessarily require you to be very strict.”

Hui says he rarely hears residents complaining about security; they do not seem to mind that access control is not strictly implemented.

“When security is good, people will take it easy. They’re just afraid of crimes, like sexual assault and burglary but if there aren’t any of those, then why should they be nervous? That’s what people are like. When they’re worried they’ll be nervous and vigilant, then they’ll let down their guard when there’s nothing to worry about.”

Currently, the management of about 60 per cent of the Housing Authority’s rental estates have been outsourced to private companies through tendering exercises, while the rest are directly managed by the Housing Department.

Johnnie Chan Chi-kau is the President of the Hong Kong Association of Property Management Companies. Comparing private and public housing, Chan says the level of security requirements depends on the scope of service provided by the estate management companies as stipulated in their contract as well as residents’ expectations.

“Residents in private housing are more accepting of [being questioned about their identity by security guards]. They think that more questioning is a safeguard of security,” says Chan. He thinks those who own their property may see tighter security as a safeguard of their investment, while public housing tenants may view it as an inconvenience. He adds security personnel in public housing are sometimes treated impolitely when carrying out strict identity checks and registration.

The difference extends to the way residents interact with the companies responsible for providing security. Chan says owners of private units tend to be more committed to monitoring management companies’ work. “But residents in public housing are different. They just sign a tenancy agreement with the Housing Department [Authority]… After the security company is hired, whether it’s expensive or not, good or bad … they don’t think there’s a problem.”

Edited by Nannerl Yau