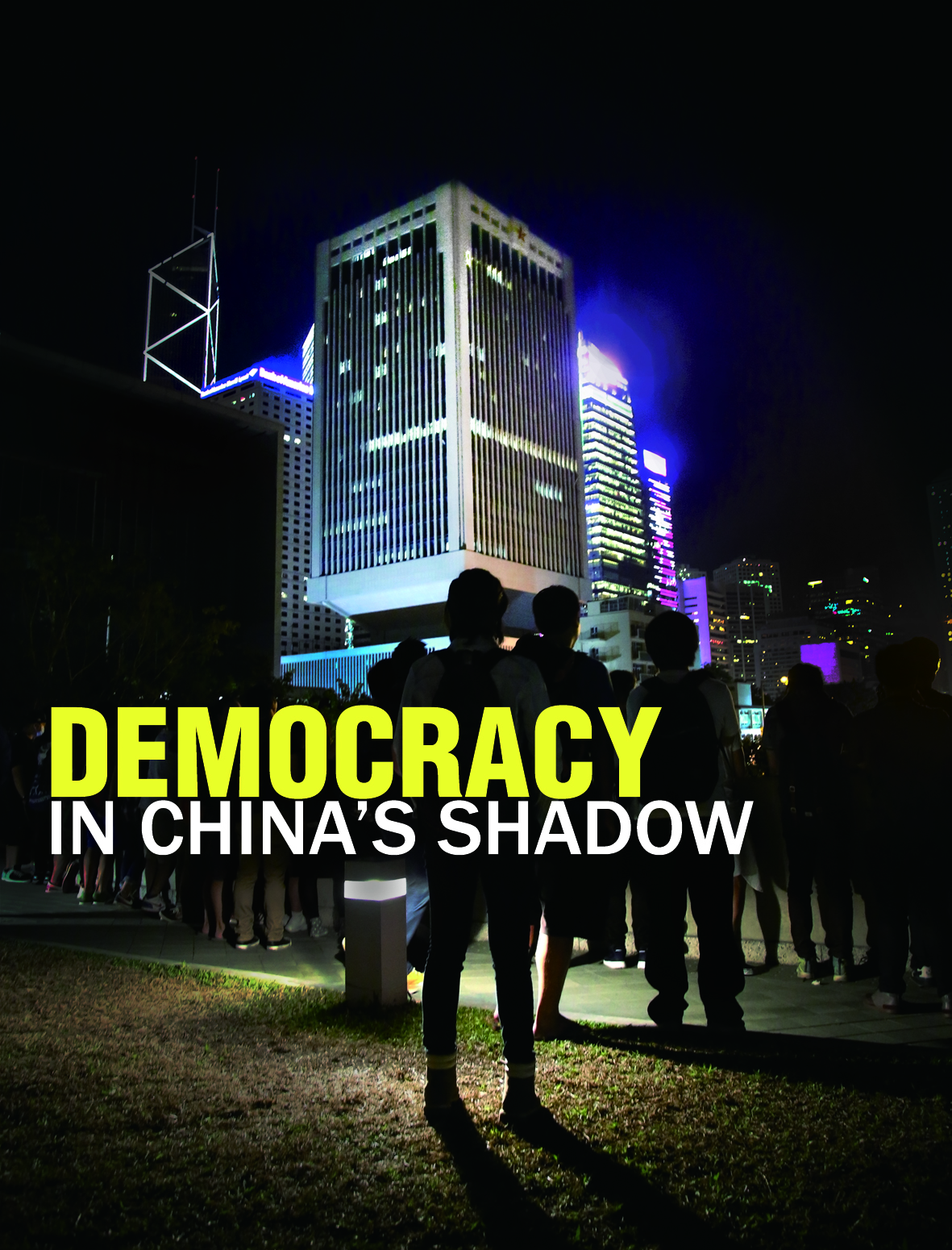

Keeping the democratic struggle alive after the Occupy Movement

By Tracy Cheung and Godric Leung

“Stop charging or we use force!”

Minutes after the final warning flag was unfurled, several blasts pierced through protesters’ angry cries as police in riot gear fired volleys of tear gas into the crowd. Streams of pungent smoke filled Harcourt Road, an artery outside Tamar government headquarters, where thousands of protesters were jostling against the police cordon. Many choked as they screamed and dashed back. More retreated to nearby Tamar Park in panic. Meanwhile, those suffering the effects of the suffocating gas kneeled on the ground in tears and breathed heavily.

It was 5:57 pm on September 28, the first day of a city-wide occupy movement to demand universal suffrage. “We had never imagined police would use tear gas on a main road,” says Angie Lam Yin-shan, a 21-year-old student protester from Baptist University who was caught in the chaos when police dispersed the crowds. “My friends saw thick smoke coming from behind. We then started running at full speed,”

Heightened tension persisted in Admiralty until 2 am. Although police fired 87 tear gas canisters and more than 40 people were sent to hospitals, thousands of protesters continued to occupy the main roads in Admiralty, Central, Mong Kok and Causeway Bay. “It’s totally unacceptable! How can the police use violence against peaceful protesters?” cried Lam, adding that many of her acquaintances had taken to the streets to protest against police violence.

Lam was a supporter of the week-long class boycott organised by university students which began on September 22. During that week, students surrounded the government headquarters and held civic lectures at Tamar Park. The protesters ended up staying after police arrested a group of students and other protesters who broke into Civic Square, the forecourt outside the Central Government Office.

This led to the midnight announcement on September 28, by University of Hong Kong Professor Benny Tai Yiu-ting that Occupy Central would begin earlier than planned. Lam chose to stay as she believed the occupy movement and the class boycott served the same goal: to fight for genuine democracy.

In recent years, disagreements on how candidates should be selected for the territory’s first Chief Executive election by one-person-one-vote in 2017 has turned into a tug of war between Beijing and its supporters and local democracy advocates.

When Beijing announced a restrictive framework for the 2017 election in August, many believed it had “closed the door” on democracy by screening out any candidates it disapproves of. Under the framework, candidates must be endorsed by half of the 1,200-strong nominating committee – which is stacked with pro-Beijing members – before they can run for the election.