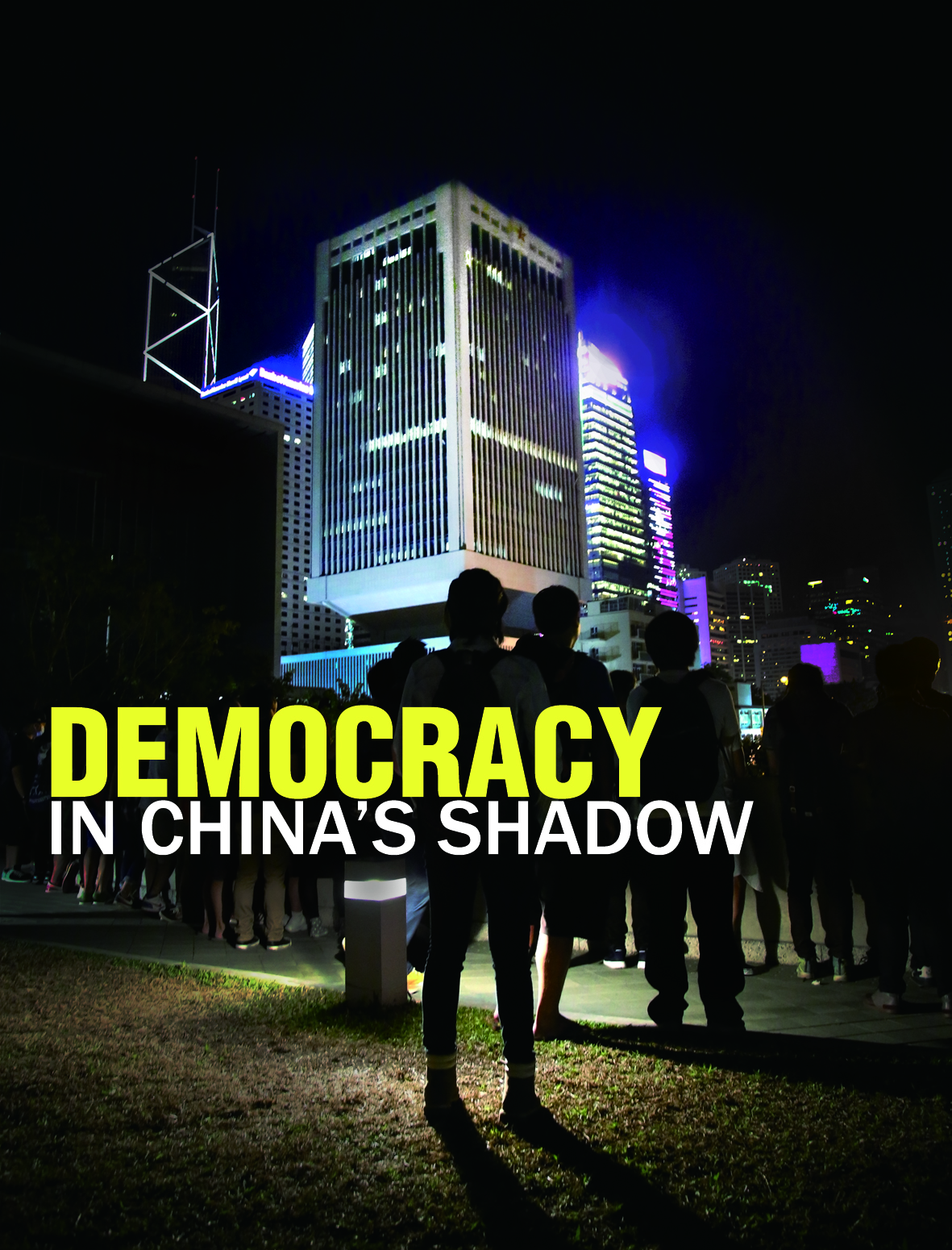

What can Hong Kong and Taiwan learn from each other in quest for democracy?

By Angel Liu and Stella Tsang

On the night of March 18th this year, student protesters in Taiwan broke through police cordons, climbed over fences, stormed into the island’s lower house of parliament, the Legislative Yuan, and occupied it. They were protesting against a trade pact with China, which they said had been passed without sufficient deliberation and due process. The occupation grabbed news headlines, and lasted for almost a month.

The movement, which became known as the Sunflower movement after a supporter brought bunches of sunflowers to symbolise the need to let the sunlight shine into the “black box” of the trade pact, found many sympathisers in Hong Kong. Slogans shouted by Hong Kong’s Sunflower movement supporters included “Today Hong Kong, Tomorrow Taiwan” and “I am a Hongkonger. Taiwan, please step on Hong Kong’s corpse and contemplate the path you want to take.”

(Photo by Wu Hsiang-Yuan)

The idea behind these slogans was clear. China’s former paramount leader Deng Xiao-ping devised the concept of “One Country, Two Systems” in 1978 to allow Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan to maintain their own systems of governance as a path to reunification. As a condition of the British handover of sovereignty to China, Hong Kong was promised 50 years of a “high degree of autonomy” under the One Country, Two Systems framework. The Special Administrative Region was meant to be a shop window for Taiwan, a blueprint showing the island the benefits of the path to reunification across the Taiwan Strait.

But while Beijing more or less lived up to its promise in the initial years after the handover, concerns have been raised about the Special Administrative Region’s (SAR’s) high degree of autonomy in recent years. Just this year, a brutal chopper attack on former Ming Pao chief editor Kevin Lau Chun-to was seen as a threat to the city’s press freedom. And a white paper issued by the State Council raised fears that the SAR’s judicial independence was being undermined.

“You cannot persuade Taiwan people to agree on one country, two systems,” says Leung Man-To, a professor at National Cheng Kung University’s Department of Political Science. In recent years, people from Taiwan have witnessed things that have happened in Hong Kong also happening to them.

“China brought Chinese economic factors into Hong Kong, and gradually changed the constitution of Hong Kong’s economy,” Leung says. “If you want to make money, you have to listen to me. China is using this to control Hong Kong, and so it will [do the same] to Taiwan in the future.”

Leung says the 2003 Mainland and Hong Kong Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement (CEPA) and the 2009 Cross-Straits Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement (CECA) are examples that show how economic penetration strengthens China’s political control.

Hong Kong’s current political impasse over political reform and the civil society initiatives to break the deadlock through social movements and civil disobedience have prompted people to ask whether Hong Kong is walking the same path to democracy as Taiwan did in the past.