But Byron Weng, a professor at National Chi Nan University’s Department of Public Policy and Administration, says there are fundamental differences between Taiwan and Hong Kong. Weng, who taught at the Chinese University of Hong Kong in the 1990s, points out that Hong Kong is geographically adjacent to the Mainland, which would not need to use much military force to take control of the city. Taiwan, however, is separate from China and has its own army.

The biggest difference, says Weng is between the opponents democracy activists face in the two places. He says the Kuomintang lives in the shadow of the United States and as an anti-communist party they have to pretend to be democratic, whereas Beijing does not have to listen to anybody. “Beijing has a way of thinking that everything is in their hand,” Weng says.

Although he is somewhat pessimistic about Hong Kong’s future, Weng says that whether Hong Kong’s Occupy Movement is successful or not, it will have a significant impact on the city.

Despite the differences in their circumstances, activists in Hong Kong and Taiwan share an aspiration for greater democracy. As the social movements in both places have stepped up a gear, ties have been strengthened. Interactions and exchange of thoughts, strategies and people are more frequent than before.

Before the Occupy Central with Love and Peace organization stepped up its action and evolved into Occupy Hong Kong on September 28, Taiwanese activists held sharing sessions about their own experience. Chien Hsi-Chieh, chairman of the Peacetime Foundation of Taiwan and a leader of the huge “red-tide” anti-corruption protests in 2006, was one of them.

In the past, Chien says, Taiwanese police always used tear gas and water cannon against protesters and they would fight back using sticks and stones. When this kind of confrontation happens, he says, the media depicts participants as thugs and if the movement turns violent, the demands of the public are neglected. Non-violent protests, however, make it impossible for police to justify the use of force.

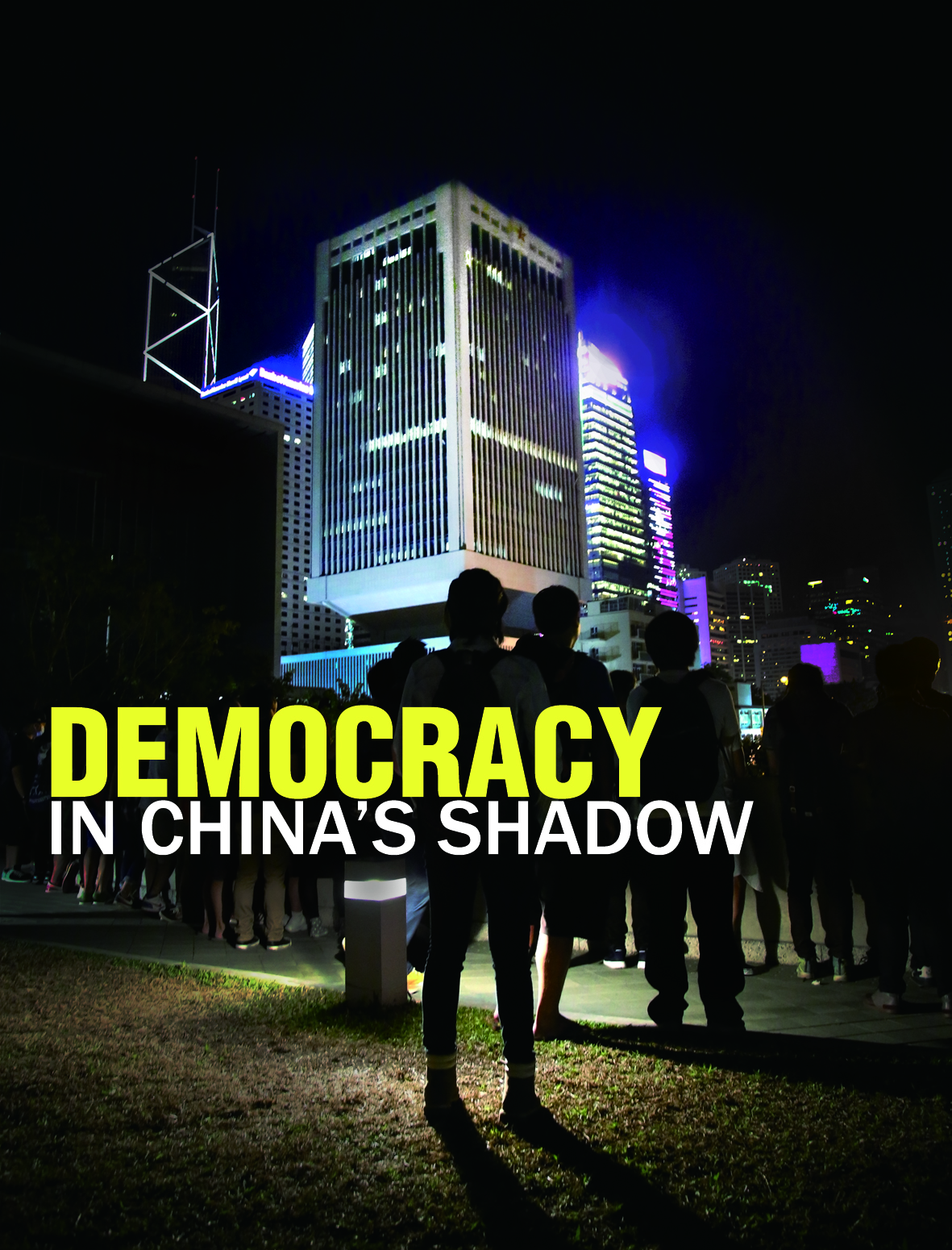

It seems that Taiwanese history may be repeating itself in today’s Hong Kong. The Umbrella Movement on September 28 showed Hong Kong people’s determination to fight for genuine universal suffrage through non-violent methods. The scene in Hong Kong looks strikingly similar to that in Taiwan, with police using pepper spray and tear gas to disperse the crowds. But what distinguishes Hong Kong from its neighbour across the strait is the protesters’ unwavering commitment to protesting peacefully.

Instead of fighting back, protesters used umbrellas to protect themselves and won plaudits from around the world while the police use of force was given wide media coverage.

“Hong Kong is like Taiwan in the 1980s and 1990s,” says Taiwan native Chang Tieh-chi, the editor-in-chief of Hong Kong’s City Magazine. Chang says the 1980s were a period of transformation for Taiwan, from authoritarian to democratic rule. At the same time, the people’s identity evolved from that of a colonized people into being Taiwanese.

The whole society went through a period of upheaval in which social and political polarization was constantly on display. Chang recalls he was a third year university student at National Taiwan University during Taipei’s first mayoral election in 1994. At that time, taxi drivers would hang flags emblazoned with the number of the candidate they supported on their cars. People on the street would make gestures at the numbers when they came across the taxis. “Every time it was like a clamour for war. It was like in the next moment, people would start to fight,” Chang says.

Hong Kong’s post-Occupy Central development has become a hot topic among Chang’s friends lately and he says they tend to have great expectations. But he believes that taking the path towards democracy is never easy. It is a long fight that cannot be won through holding a few demonstrations, and it would be impossible for people to not pay a price.

“The most important thing is that failure this time should not become defeatism,” Chang says. For him, Occupy Central is just a beginning and failure to get what people want at this stage does not represent the end of Hong Kong. “Hong Kong has to be prepared to enter a time of all-round fights among different groups and in different fields.”

He says if the National People’s Congress Standing Committee insists on their decision on the 2017 political reform, Hong Kong people still have to stand up and fight for their basic rights like freedom of speech and judicial independence, otherwise, these core values may be gradually eroded. “The important thing is how you create your own future. Every individual makes a little struggle in a critical era,” Chang says.