Upcycling designer Kevin Cheung Wai-chun tells stories of waste materials by turning them into new products.

By Soohyun Kim

Among the myriad of skyscrapers in Wan Chai, there is a four-story tenement block in blight blue colour, Blue House. Inside the iconic historic building, there is a small two-storey room filled with rustic rice cooker bowls and broken umbrellas, dimmed with a ceiling light made of discarded bicycle rims.

Dubbed “the rubbish guy”, resident of the unit, Kevin Cheung Wai-chun enjoys doing treasure hunt in filthy garbage and wastes. Although he no longer does dumpster diving now, the 32-year-old upcycling product designer collects rubbish as raw materials for his creations.

Turning the rotten into miracles

Since 2011, Cheung has been working with various kinds of wastes to create new products — a practice of upcycling. Upcycling is a process of transforming unwanted materials into new products of better quality. The practice is different from recycling because it does not involve the breaking down of materials. “When we talk about upcycling, we try to preserve the material as it is. We try to turn it into something else without changing it a lot,” says Cheung.

Cheung used to be a product designer at a battery company designing flashlights, power banks, battery chargers and other similar products after graduating from the School of Design at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Yet Cheung saw limited room for creativity while working for that company. “Something was missing throughout the process of designing for a company,” he says. “You just get the parts and draw a beautiful box around it, and we call it [a] new product.” He also acknowledges the short lifespan of products he used for designs, as most break down within two years.

Cheung started studying the practice of upcycling to pursue creativity with an environmental consciousness. The first product he created was a Boombottle, a speaker made from a plastic bottle. He made the first two Boombottles and joined a friend who sold handmade books in a flea market in September 2010. Since then he has been creating other upcycling products, such as Rice Bell, bicycle bells made of discarded rice cookers and Lumi-rim, a ceiling light created with thrown-away bicycle rims. His customers can find these products online and at four offline retail outlets.

Lacking a way out

Hong Kong has long been struggling with waste problems. Regarding statistics from the Environmental Protection Department (EPD) in 2017, around 15,516 tonnes of municipal solid waste were produced per day. The three landfills, in Tseung Kwan O, Tuen Mun and Ta Ku Ling respectively, are expected to be full by 2020.

Cheung points out the difficulty of recycling waste materials in Hong Kong due to the absence of a manufacturing industry. “We don’t manufacture anything so we cannot use waste material ourselves, we have to send it off to somewhere else,” he says. “We don’t really have much to say.” Recent changes in the Chinese government policy on imported waste have also aggravated the problem. “[Under the policy,] Hong Kong cannot export raw waste material without filtering, while Hong Kong lacks a facility for waste filtering or recycling,” he says.

Despite the poor recycling standard in Hong Kong, Cheung has seen improvement in the recycling industry as the government has started to find better waste treatment methods. He cites the local waste paper recycling and manufacturing plant that will be open next year in Tuen Mun as an example. “That’s a new baby step we are taking,” says Cheung.

Challenging the misfortune

Cheung observes that Chinese people associate rubbish with misfortune, “[The waste]’s for the dead people, it brings bad luck. I think that has to be changed,” Cheung says.

To create less waste, he emphasises the idea of “thinking twice before buying”. He also conducts educational workshops in hopes of raising social awareness. Cheung explains the idea of the workshop is to help Hong Kong people adopt habits of using their own hands to create or fix belongings, instead of buying new things they need. “[The habit of making something with your own hands] is really important because when you stop using your hands, whenever you need [something], you just use money to buy it,” he says. “That also is a problem that ends up creating a lot of waste. People stop fixing it (things).” Cheung provides life-warranty to customers for his products. “No matter [how long], even four years, or five years….If it breaks, you bring it back to me and I will fix it for you.”

Whenever [how long], even four years, or five years…If it breaks, you bring it back to me and I will fix it for you.

Expanding the spectrum

As a consideration for budget as well as the nature of the waste material, Cheung plays around with waste from corporates. Whenever he finds waste materials that are interesting in a landfill, he contacts relevant companies and asks for the materials before they are dumped in landfill.

It was not easy at the beginning. “[At first,] they were quite reluctant to give you the waste because they were not sure what you were doing,” Cheung says.

The table has been turned upside down now. As Cheung has built a notable portfolio, local and multinational companies have started reaching out to him for collaborations. With his range of products and philosophy, he has attracted corporates like Citibank and non-governmental organisations (NGO) such as Greenpeace for commissioned projects. “Everything I’m trying to do, it’s not just doing things that I like, but trying to inspire big corporations because they are the ones making the impact,” Cheung says.

He notes most companies pursue a glamorous style when organising events but it is not difficult to move away from that culture. “When one company does it, with a positive impact, it’s very easy to inspire other companies to follow.”

Aside from collaborating with the commercial companies, Cheung has worked with St. James’s Settlement, a non-profitable organisation located in Wan Chai. The NGO runs sheltered workshops for people with disabilities, and the workers have been helping Cheung with assembly work on his products.

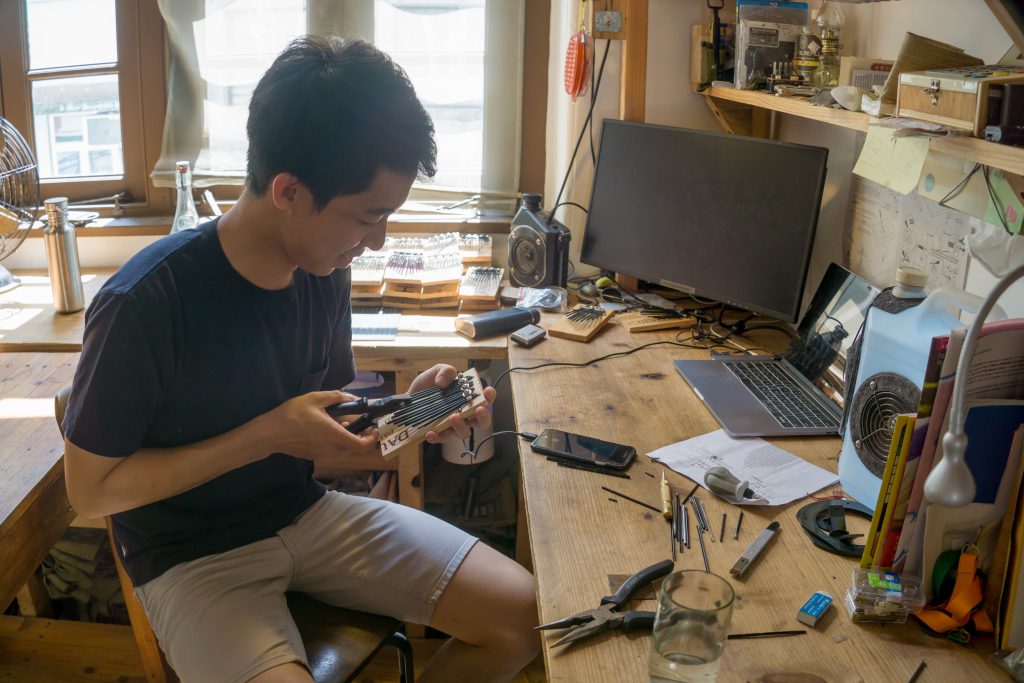

Cheung’s creativity is not limited to companies and social enterprises, his work also relates to social movements. During the 2014 Umbrella Movement, Cheung collected broken umbrellas that were left on the streets after clashes and created thumbnail pianos with ribs of umbrellas.

Cheung sees a close linkage between social movements and environmental protection. He cites new initiatives following the Umbrella Movement, such as “Waste-no-mall”(不是垃圾站)in Yuen Long and the “No More Junk Bay”(正澳) in Tseung Kwan O.

He says: “[The movement] has gathered a lot of people who are willing to change the society. So that actually became a big momentum to continue to change in the society when they go back to the communities and recycling is one point (one of the changes).”

Cheung re-creates his thumbnail piano using newly collected umbrellas used by protesters in the anti-extradition law amendment bill movement. The thumbnail piano plays notes to “Do you hear the people sing?” and “Glory to Hong Kong”, the two anthems frequently sung by movement supporters, which give a special meaning to the piano.

“No matter how it (the movement) ends, this time it should lead to good changes,” Cheung says.

No matter how it (the movement) ends, this time it should lead to good change.

A storyteller and a dreamer

The upcycling designer prefers to be named as storyteller. “When you work with a lot of waste materials, a lot of stories behind… it kind of grabs onto you.” He compares his work with the Blue House — one of the historical landmarks in Hong Kong, which is also where he resides. “It’s an old architect[ure]. The city thinks it is useless and old but once you renovate it, it becomes a modern, stylish living space. It’s a similar metaphor,” he notes.

“I think they (customers) are not just buying the products.” He believes every material carries its own story, which becomes the foundation for his design.

“Interesting thing about waste is that it’s always related to the city. Something happens in the city, that kind of waste is produced,” Cheung says. He notes these stories are what entertain and surprise people. “The surprise on the[ir] face[s] keeps me going.”

Interesting thing about waste is that it’s always related to the city. Something happens in the city, that kind of waste is produced.

Cheung says he has achieved his ultimate goal as he enjoys doing what he is doing. But he still hopes to see “what end up in bins can end up on shop shelves and start all over again” in the near future.

Edited by Jasmine Ling