Schools pull out of a debate contest after a Chinese state media has raised an outcry over debate motions which they call “politically sensitive”.

By Fiona Cheung and Gloria Wei

Twenty-six schools, about one-fifth of the participating teams, withdrew from the Hong Kong Secondary School Debate Competition after debate motions related to anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill (anti-ELAB) movement sparked controversy in late December last year.

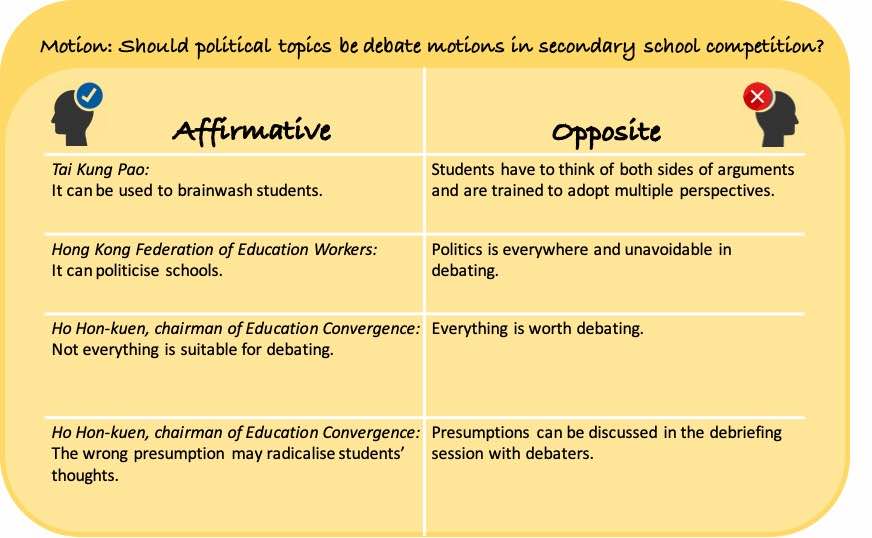

The action came after Ta Kung Pao, the state newspaper, criticised contest organiser of “brainwashing students” in a news article dated December 20, 2019, with a title “Education fails, Interschool Debate Contest becomes a means of Brainwashing Students”. (教育病了 | 縱暴派辦學界賽 假辯論真洗腦)

(Source: Ta Kung Pao)

Controversy over debate motions

“Not everything is suitable to be a debate motion,” says Ho Hon-kuen, the chairman of Education Convergence, a pro-government organisation, when interviewed by Ta Kung Pao in the news article. He thinks some of the motions have wrong presumption which may radicalise students’ thoughts.

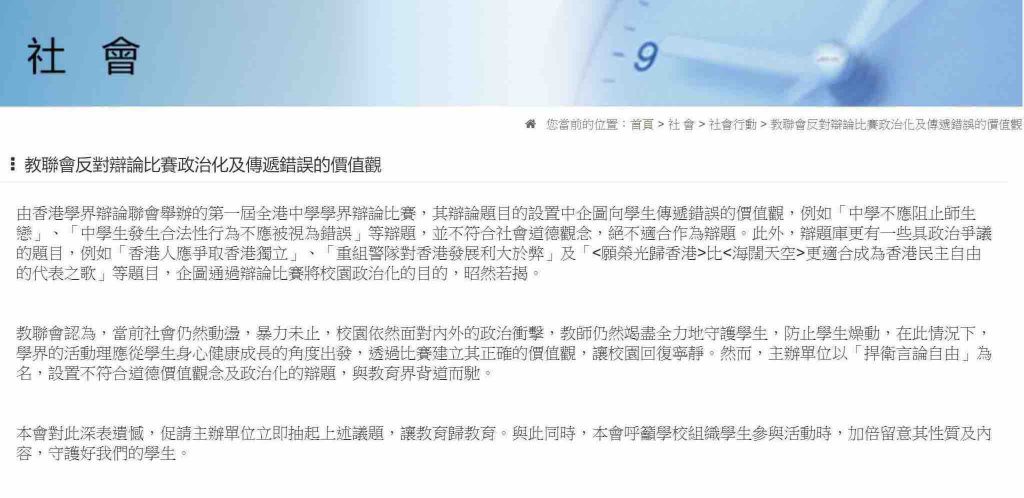

Debate motions like “Hongkongers should fight for Hong Kong independence” and “Restructuring the police force does more good than harm to Hong Kong” are denounced by Hong Kong Federation of Education Workers (HKFEW), a pro-Beijing teachers’ union, accusing the organiser of proposing inappropriate topics in the name of “defending freedom of speech”.

“The ulterior motive of attempting to politicise school campuses through this debate competition is obvious,” HKFEW says in a statement issued on December 19 last year.

(Photo courtesy of Education Convergence)

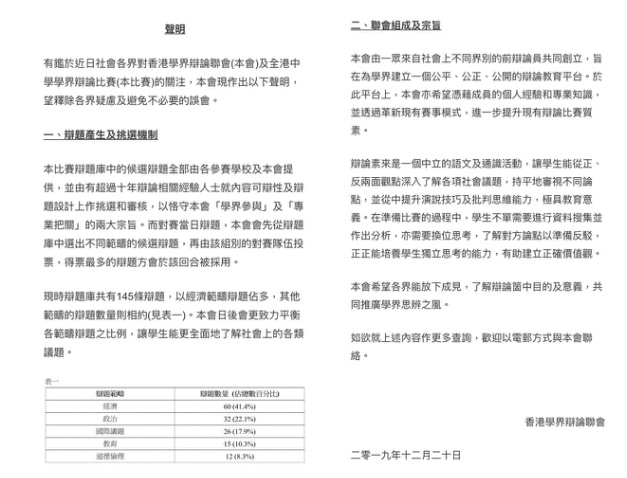

The first-ever Hong Kong Secondary School Debate Competition is organised by the Hong Kong Schools Debate Federation (HKSDF) with more than 120 participating schools. The application started in October 2019 when police and demonstrators were squaring off each other during the anti-ELAB movement.

Debate motions were proposed by applicants. The motions were then evaluated by a panel with members who have more than 10 years of debating experience. They examined the motions to see if they were debatable and whether the usage of wordings was accurate.

Hong Kong has been plagued by the anti-ELAB movement after the government proposed a controversial amendment to the fugitive offenders bill in February 2019. A public backlash sparks off protests and now includes demands to fight against the escalating police brutality and the tightening grip of China.

Responding to the pull-out of 24 schools from the contest in December 2019, HKSDF says in a written reply that they are disappointed with the schools’ decision to withdraw. “No school should be exposed to such pressure for doing something that has long been a major part of education,” the statement reads.

No school should be exposed to such pressure for doing something that has long been a major part of education.

HKSDF refuses to self-censor debate motions amid severe criticisms made by the state media outlet and pro-Beijing teachers’ organisations. “We try our best to explain our values and ideas of the debate contest,” HKSDF writes in a reply, “We will keep doing all of these.”

(Photo courtesy of HKSDF)

Everything is debatable

A secondary school debater who addresses herself as Jose is one of the participants of the Hong Kong Secondary School Debate competition. The Form Five student finds the “brainwashing” accusation made by Ta Kung Pao ridiculous. “We have the affirmative side and the negative side in a debate, so I do not see how we can be brainwashed,” Jose says.

Jose started joining debate competition five years ago. She thinks debate motions adopted by HKSDF are timely and “more grounded”.

“Many debate motions have been used many times in other competitions and we even call them ‘motion of all ages’,” Jose says, “The debate topics selected by HKSDF are about current affairs which are really worth discussing.”

As Jose is looking for opportunities to discuss more “innovative” topics, she shares her view that everything is worth debating. She thinks debate motions cover all kinds of topics and it is natural that some topics might touch on politics. “Nothing is absolute after all. Anything can be a debate motion,” says Jose.

Nothing is absolute after all. Anything can be a debate motion.

Another student who identifies herself as Ann was one of the participants of the Hong Kong Secondary School Debate Competition. Her school was one of the 24 schools which decided to pull out from the contest. Students were not consulted and were only informed about the decision afterwards.

“It is our freedom to choose whether to join the competition or not,” Ann says, expressing her disapproval of being forced to quit the event. “I feel like we are being suppressed and the opportunity of participating in the match is taken away,” she adds.

Equipped with three years of debating experience, Ann cites debate motion such as police disbandment as an example to explain how the topic can help students develop an intellectual discussion.

“For example, discussing police disbandment does not only target on police brutality, the discussion also covers other related issues such as the impact on governance and overseas experience,” she says, “We don’t simply argue on police brutality but we have to discuss issues like power vacuum with examples from foreign countries.”

Debating politics at schools

The political storm over the debate contest not only affects participating schools. A secondary school which did not take part in the competition received a letter from the Education Bureau due to parents’ complaints about some interschool activities which were perceived to be held in favour of the anti-ELAB movement by parents. A teacher who identifies himself as Keefe was the organiser of a friendly debate competition.

Since some debate motions of the friendly match touched on political topics, Keefe also received a letter from the Education Bureau, requesting him to explain motives behind the match and the motion, the number of participants and whether alumni were involved.

Concerns from parents, school management, sponsoring body of the school and his colleagues were aroused when Keefe was preparing to organise the match. He realised a political storm might have been triggered even if he had kept the match low-profile to avoid public attention. People around him might also be affected if the match continued.

“I realise things are beyond control once they are related to politics,” Keefe says, “I tell my school I am willing to bear any consequences but then I notice some consequences cannot be borne by myself.” He had no choice but finally compromised – no political topics when setting debate motions in future competitions.

Keefe believes it is hard to brainwash students simply by debate motions. “Students can have their own stance,” he says, “and their stance does not have to be the same as the stance they are assigned to in a competition.”

He believes forbidding students to discuss politics is in fact politicising schools. “The Education Bureau is the one which politicises schools by banning certain ideas such as Hong Kong independence to be discussed. This limits students’ thoughts. It is the bureau which brings politics to schools,” Keefe says.

The Education Bureau is the one which politicises schools by banning certain ideas to be discussed.

Prospect of students debating

A debate coach of a secondary school surnamed Wong, who refuses to disclose his full name, worries criticisms over debating politics will affect future development of debate training in secondary schools.

The school he works for also participated in the Hong Kong Secondary School Debate Competition.

“I think the future of students debating is definitely going to be harder in Hong Kong,” says Wong, “The future development depends very much on whether debaters uphold the value of searching for truth as we say everything is worth debating.”

The future development depends very much on whether debaters uphold the value of searching for truth.

Concerning the controversial debate motions, the Education Bureau says in an email reply, “Many of the motions are related to the current social incidents with a slanted angle of topics. It makes people suspect that there is a strong propagandistic purpose.”

The bureau sent notices to various schools, stating the basic principles of teaching controversial issues with unbiased and pluralistic views since late August 2019, but refused to provide an exact number of notices or letters issued to teachers and school upon enquiry.

Edited by Tiffany Chong