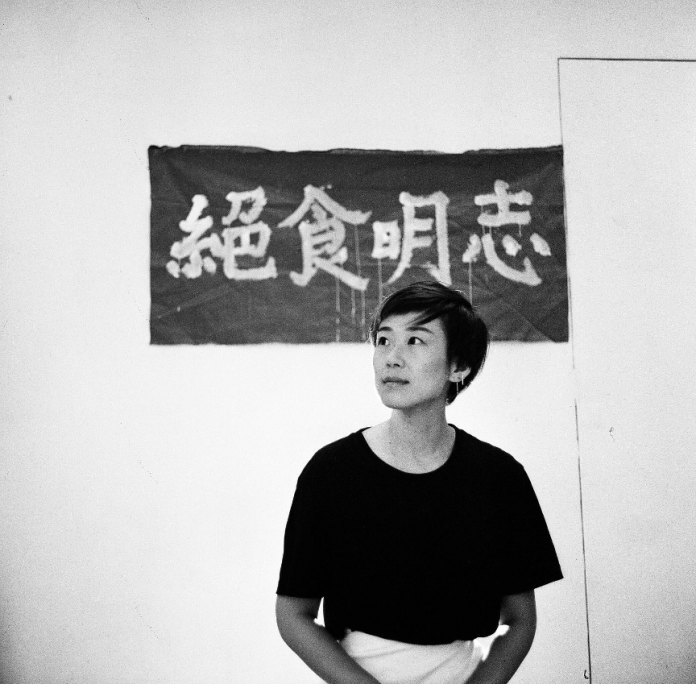

A pro-democratic Shanghai-born Hongkonger helps new immigrants speak out and fight against discrimination for Mandarin speakers in the city.

On February 21, 2020, a mainland-born sociologist Minnie Li Ming went to a “yellow restaurant” which supports anti-extradition bill movement protesters.

The restaurant operated by Kwong Wing Catering announced on January 28 that it would “only serve Hong Kong customers and accept orders in Cantonese or English” on its Facebook page.

“I don’t want to see our society become so radically antagonistic,” Li says. “Mandarin speakers are not enemies of (Hong Kong) society.”

Li, together with her five Mainland immigrant friends and two Hong Kong friends visited the restaurant and ordered food in Mandarin, but the staff insisted on serving them in Cantonese. They finally managed to make an order by writing.

The restaurant owner who promised to meet her in the evening that day did not show up at the end, nor did he respond to Li’s message. When leaving, Li and her friends gave the restaurant staff some masks and hand gel to thank them for being supportive of the social movement.

“I failed to communicate with the owner, but someone has to give a try,” Li says.

From a Stranger to a Hong Kong Pro-democrat

Li, 35, is now a lecturer of the Education University of Hong Kong. Sharing the Chinese name of superstar Leon Lai Ming, she is an immigrant from Shanghai. After finishing her undergraduate study at Fudan University, she came to Hong Kong to pursue further studies at the Chinese University of Hong Kong in 2008.

She is known to the public mainly because of two hats she wears: A Mainland immigrant and a high-profile supporter of the pro-democracy camp in Hong Kong. When she started her postgraduate study, she was a supporter of the Beijing government and planned to return to the Mainland after graduation.

“But gradually I felt I couldn’t go back (to the Mainland) … My thoughts have changed. I can’t get used to it (social environment of the Mainland) anymore,” says Li. “You can’t say what you want to say, care about what you want to care. You can only work hard to make money like my peers.”

On June 4, 2009, she attended a candlelight vigil at Victoria Park for the first time – where tens of thousands of people gathered to mark the anniversary of the pro-democracy movement in Tiananmen Square, Beijing. Li, in her 20s, changed her view on what happened in Beijing on June 4, 1989 after the visit. “I found that what I learnt in history lessons in the Mainland was wrong,” she says.

Gifted in language and having grown up in a metropolis, Li integrated well into Hong Kong. She has become a pro-democrat.

Like many Hong Kong young people, she took to the street during the Occupy Central Movement in 2014. Knowing that students were protesting at Civic Square, an open space outside the Central Government Offices in Admiralty on September 26, she bought some water and food, hoping to lend a helping hand to young protesters there.

“I’ve never been there before,” says Li. “I didn’t know it was impossible to deliver water and food to the protesters until I got there.”

Witnessing a social movement of such a large scale for the first time in her life, Li was both overwhelmed and curious. Although she stayed at the back of the crowd, she was still pepper–sprayed by the police.

Li’s father came to Shenzhen to visit her the day after the protest. She recalls her father’s reminder: “You are a Shanghainese but not a Hongkonger. Even though you support them and join the movement, they still call you ‘locust’. Then why did you go there?”

His words made Li think about her identity and relationship with Hong Kong. She then figured out that her support for the social movement is not based on identity, but the ideology she believes in.

Encourage New Immigrants to Speak Out

Li used to work part-time at Midnight Blue in 2015, an organization aiming to protect rights of male and transgender sex workers. The experience makes her realise that she has integrated into Hong Kong society so well that she has overlooked difficulties other new immigrants encounter. She finds new immigrants are just like those transgender sex workers, they are both not accepted by the mainstream.

“The public think sex workers are shameful due to prejudice and lack of understanding,” she says. “Similarly, new immigrants are thought to be greedy locusts.” She believes misunderstanding can be reduced when people learn more about new immigrants.

On May 31, 2019, Li organized a signature campaign against the proposed extradition bill, but most new immigrants who supported the campaign only signed their surname fearing of getting into trouble. “They are as miserable as the gays go to a church,” she says.

To make a change, Li led a group of new immigrant protesters on June 9, 2019 in a demonstration. She held a huge banner that said: “Do not ask where protesters come from. New immigrants protect Hong Kong”. Participants gathered under the banner belonging to new immigrants for the first time.

Their action received a warm welcome from many local protesters, although occasionally they faced discrimination which made them feel very upset. But Li still hopes new immigrants can make themselves visible in Hong Kong by participating in the social movement. “Being visible and accepted is a source of power,” she says.

“We are not just a cheering squad for local protesters. We are a part of the society. We also fight for ourselves,” she adds.

Li also invited members of the New Arrival Women League, an organization consisting of grassroots female immigrants, to join them. “The image of new immigrants ought to be enriched, rather than being limited to the intellectual or middle class,” she says.

“Integrity Is the Only Way Out”

Despite her high-profile involvement in pro-democracy movements in Hong Kong, an article she wrote about her visit to Kwong Wing Catering caused a heated debate in social media platforms. Some supported her, but some criticised her of provoking the restaurant operator to find flaws with ill intentions, though she holds the same political stance and views with them in the anti-extradition bill movement.

But Li does not regret going to the restaurant. “They just carve some people out of the society with a simple and arbitrary standard according to their stereotype, without considering the complexity of identity in the real world,” she says.

Li believes people should not label or hurt others for speaking different languages, and every individual is unique and should not be judged by certain standards, especially in a social movement. Otherwise, a cutthroat world will be created. “The movement should make people feel being respected,” she says. “It is wrong to think that people are just instruments and dignity is insignificant.”

She says that her biggest worry about the movement is some people may abandon their ethical standards. In an article she posted on her Facebook, she wrote: “As Albert Camus wrote in his novel Plague, integrity, which means doing what you are obliged to do, is the only way out.”