Despite effort to ease pressure on school pupils and parents, the Chinese education system remains competitive.

By Ella Lang

Mary Li enrolled her eight-year-old son in English, drawing, and Lego classes when he was four. When the boy started to go to primary school, other than 40 hours per week in school, he had to spend nine hours on five after-school classes including English and Mathematics.

“Every parent in Shanghai does the same thing. Children will fall behind if they do not take extra classes,” Li says.

Li’s family spends about RMB ¥60,000 (US $9,282) a year on tutoring classes and has spent over RMB ¥200,000 (US $30,940) since her son started attending tutoring classes. Every year countless families fork out for off-campus classes for their children, contributing to the booming tutoring industry in China.

“CHILDREN WILL FALL BEHIND IF THEY DO NOT TAKE EXTRA CLASSES.”

The market size of China’s after-school tutoring for kindergarten to 12th grade (K-12) students reached RMB ¥800 billion (US $123.7 billion) in 2019, and was predicted to break RMB ¥1 trillion (US $0.15 trillion) by 2025, according to a 2020 report by management consulting firm Oliver Wyman.

China banned for-profit tutoring in core education to rein in the country’s private education industry and improve school-life balance for families in July 2021. The policy, dubbed “double reduction”, aims at releasing the burden of off-campus tutoring for students at the stage of compulsory education and excessive homework assigned by schools.

Under the new policy, all private tutoring institutions are banned from making profits by providing tutoring services of school curriculum subjects such as English and Mathematics during weekends, holidays, or after 9:00 p.m. on weekdays. Tutoring is only allowed on weekdays with a limited number of hours.

(Source: The State Council of The People’s Republic of China)

After the “Double Reduction” Policy

Li signed up her son for English and Mathematics tutoring classes on Monday and Friday respectively before the “double reduction” policy was introduced. Each lesson lasts for two hours and ends before 9:00 p.m. Her son also has calligraphy, street dance, and basketball classes during weekends.

“All arrangements can remain unchanged because they all meet the time restrictions. But I still dropped Mathematics class provided by leading training organisation Xueersi(學而思)for my son, as he has to stay in school for one more hour. That is quite tiring for him,” Li says.

The “double reduction” policy came with many supporting measures. One of them is to make students stay at school longer by providing free after-school services. Teachers will either help students finish their homework or carry out extracurricular activities based on students’ interests during the extra hours after school, according to a circular issued in June by the Ministry of Education.

“But if my son fails to perform well in school when he goes to high school, I will still sign him up for private tutoring classes,” Li says.

Many parents in China like Li are still worried about their children’s education, although the “double reduction” policy aims to reduce student’s burden and ease parents’ anxiety.

Another anxious parent is Zhou Chunmei in Kunming, the capital city of Yunnan province. The English tutoring agency her son used to go for classes has stopped offering lessons after the policy was introduced. Luckily, she received a full refund from the agency.

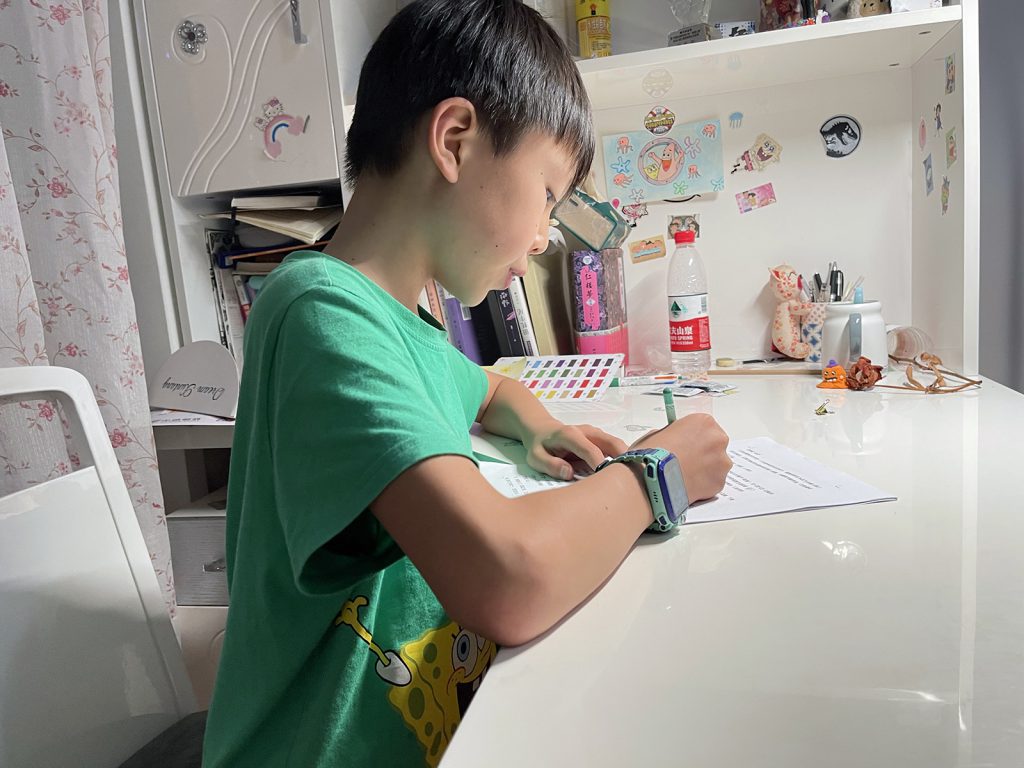

Her nine-year-old son Yi Zhishan feels happy about the change. His weekends used to be filled with off-campus classes since he was seven with drawing, piano, programming, tennis, and English classes.

“The English class used to take three hours. Now I can spend time with my friends and family instead,” Yi says. “I am so happy that I can go to amusement parks more often!”

(Photo Courtesy of Zhou Chunmei)

But his mother is still planning to sign him up for English tutoring classes later. “I will wait for a while to see how the policy is implemented. If the restriction loosens, I will get my son to do English tutoring again,” she says.

Zhou is worried about her son falling behind his peers. “If everybody quits off-campus tutoring, then I will certainly applaud the ‘double reduction’. Both parents and students can escape from fierce competition and take a breath of relief. But in fact, the competition still exists,” Zhou says.

Another parent, Selena Zheng, has to cancel Chinese and Mathematics private tutoring classes for her ten-year-old son because the private tutoring agency is no longer allowed to offer classes on weekends. Zheng saves RMB ¥20,000 (US $3,094) per year by cancelling the classes, but she cannot feel any pleasure from this.

“I am quite worried that he may not learn as well as before. Without extra classes, students’ self-motivation becomes more important,” Zheng says.

She adds that her son is also not happy about this, as he feels stressed about fighting for a school place of an elite secondary school after becoming a fifth grade student this September.

“As long as there is a university entrance examination, parents will never stop feeling anxious,” Zheng says.

“Those tutoring agencies took care of my anxieties and worries about my child’s education before the ‘double reduction’ policy was implemented. So, now I feel more stressed without the tutoring agencies, and I cannot find a way out,” she adds.

No One Will Stop

Edward Vickers, professor of the Department of Education at Kyushu University, thinks the new policy will not solve the problem.

“The competition will continue, but it will take new forms. Most families will face considerable struggles,” Vickers says.

Vickers thinks private tutoring will continue at private homes on a one-to-one basis, in ways that are very difficult to monitor and in ways that will increase inequality. “You will have to be wealthier to afford,” he says.

He adds that the South Korean government made a radical attempt to crack down private tutoring agencies years ago, but it did not work.

“Because you are not dealing with the demand for tutoring. The Chinese government is only dealing with the symptoms of the disease of educational competition by closing down tutoring agencies, but not dealing with what is causing this educational competition, which is credentialism,” he says.

“Because you are not dealing with the demand for tutoring.”

Edited by Vivian Cao & Gloria Wei

Sub-edited by Lynne Rao & Linn Wu