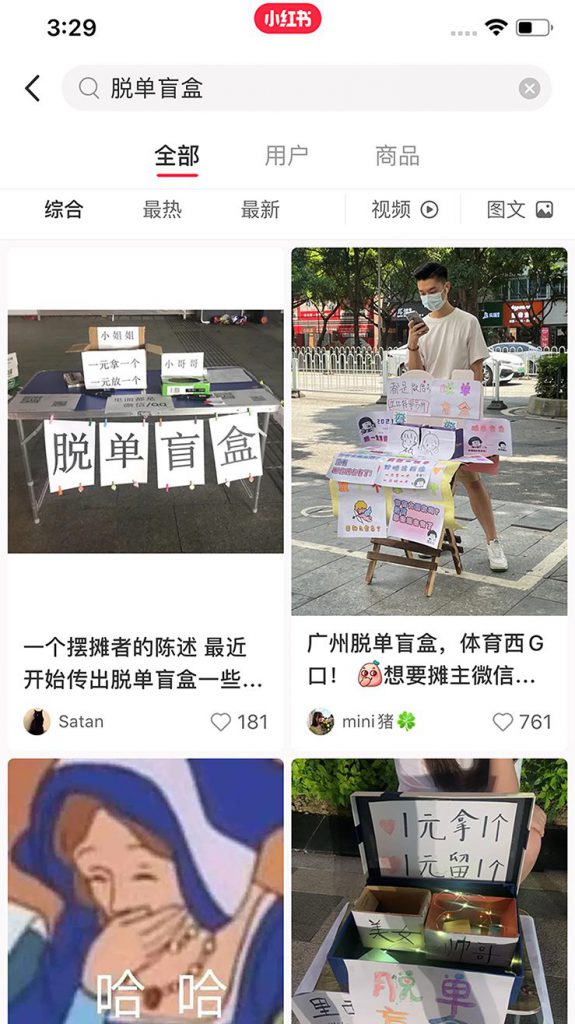

Young people in China have come up with a way of exchanging contacts through blind boxes to meet new friends.

By Ryan Li

Steven Zhang*, a 25-year-old bachelor in Guangzhou, China, joined Blind Box for Love on September 13, 2021, wishing to find a lover.

He received two friend requests through WeChat, an instant chat application in China, after leaving his contact in a blind box that cost him RMB ¥2 (US $0.31). He had chats with his new friends, exchanging basic information such as age and hobbies.

“I have very long working hours and have no time to make new friends,” says Zhang who works in the construction industry. He thinks that Blind Box for Love provides a new way to start a romantic relationship.

Zhang has already participated in several different blind box activities since September 10, 2021. He has added contacts of 10 girls to his WeChat friend list so far. They have short and simple conversations most of the time due to “lack of common topics”.

Inside the Blind Box

Blind Boxes operate like toys packed in boxes with the same appearances and sold by vending machines or in stores. In Blind Box for Love activities, or Tuodanmanghe (脫單盲盒) in Chinese, buyers pay for a blind box containing a note with contact information of a stranger.

A participant can leave his or her WeChat account on a note in a paper-made blind box or take a note left by others. No further information other than gender is required. Each box costs RMB ¥1-2 (US $0.16-0.31). Then participants can make use of contact information inside blind boxes to start a conversation through WeChat.

Katrina Pan*, who is a 19-year-old university student in Nanyang, Guangdong province, left two notes with her contact in a blind box activity on September 1, 2021.

“I wanted to see what kind of people I would meet by luck, out of curiosity. But it largely depends on what the participants are like,” Pan says.

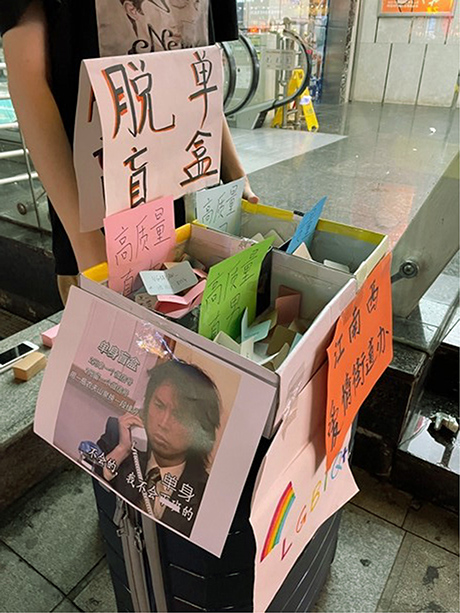

Blind Box for Love has two categories with one for heterosexual lovers and another for homosexual group. As a member of LGBTQ+ community, Pan was contacted by two girls.

“I wanted to see what kind of people I would meet by luck.”

However, she only chatted once with them upon adding on WeChat, with no further interactions. Pan is disappointed and thinks that she will not try the blind box again. “There are too many uncertainties,” she says.

Unexpected Popularity

One of the Blind Box for Love activities that Zhang and Pan joined was held by Huang Shiwen, who operates a blind box stall and prepares blind boxes for participants together with her two friends.

(Photo courtesy of Huang Shiwen)

Huang, a 20-year-old student majoring in economics at the University of Washington in the U.S., has been staying at home in Guangzhou for online study because of the pandemic.

She spotted the trend of Blind Box for Love activities on RED, a Chinese social media platform where users share their life experience, on August 24, 2021. She was inspired by the idea so she started her own stall.

“We have multiple channels to meet friends nowadays, but the blind box seems purer to me compared to online dating applications. No extra information needed. It is all about luck,” she says.

“We have multiple channels to meet friends nowadays, but the blind box seems purer to me compared to online dating applications.”

Three days after coming up with the idea of setting up a stall, Huang and her friends stood by the street of Jiangnanxi, a business district in Guangzhou, Guangdong province.

Huang makes about RMB ¥250 (US $38.78) a day in total, involving 100 to 150 participants per day on average. “We didn’t expect so many people would be interested. From 8:00 p.m. to 10:30 p.m. every day, none of us have taken a rest,” she adds.

(Photo courtesy of Huang Shiwen)

Huang and her friends also initiated an online version. People leave their contacts to Huang through private messages on RED, and Huang then writes a note for each of them and drops it into a blind box.

According to Huang’s observation, most of the participants are female college students, while male participants are at the age of 25 on average.

Huang thinks some of the participants do have the expectation of finding partners through blind boxes. “Everyone understands that the chance is rare,” she says.

“But it’s still good to have one more friend for your contact lists and gives likes to your posts on WeChat even relationship does not work out,” she adds.

A New Option

Chan Lik Sam, associate professor at the School of Journalism and Communication at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, believes that young people’s desire of meeting new people and the “luck by chance” principle of the game are the two factors that make Blind Box for Love popular.

“Young people do have the desire to make their peer circle bigger, which has motivated the development of dating technology,” says Chan, who researches online dating applications and interpersonal communication.

“While dating technology is visually driven, the blind box’s rule is designed to have WeChat ID as the only information, thus resulting in participants’ lower level of purposefulness,” Chan adds.

“The blind box’s rule is designed to have WeChat ID as the only information, thus resulting in participants’ lower level of purposefulness.”

In one of his research papers published in 2020, Chan looked into multiple uses of Momo, a Chinese dating application. He suggested that informants demonstrated dislike towards strong “mudixing” (目的性, purposefulness) when using dating apps.

Chan also holds the view that young people in China seem to be unwilling to date “in any form”, which also contributes to the popularity of Blind Box for Love.

* Names changed at interviewees’ request.

Edited by Lynne Rao

Sub-edited by Vivian Cao