Amid rising attention to Hong Kong cultural heritage by the young generation, the Central Market is newly opened to the public.

By Felicia Lam

Casper Yam Ming-ho is so passionate about heritage conservation that he started an Instagram page called Commosus in June 2021.

“I first learnt about heritage conservation when I was a kid. My grandpa took me out weekly for lunch at a restaurant near Lui Seng Chun. I enjoyed looking at the old building at that time. I think conserving heritage sites is meaningful as it can keep the history of Hong Kong alive,” he says.

Lui Seng Chun is an old Chinese shophouse which was built in 1931. It is a Grade 1 historic building and is currently operated by the Hong Kong Baptist University as a Chinese medicine healthcare centre.

“My friends started to care more about heritage sites as they recognise themselves as a Hongkonger and grow a stronger sense of belonging to the city. They ask me to take them to heritage sites in Hong Kong,” says Yam.

“I am glad to see that public awareness about heritage conservation has increased in recent years. Public awareness is essential to push the government to protect historic sites,” he adds.

Yam finds that many social media pages are promoting Hong Kong culture and heritage conservation, but he thinks many page owners lack professional knowledge about conservation and heritage sites.

“Some of the page owners express their opinions based on inaccurate information, and their views on conservation projects are biased. Their views may misinform the public about heritage conservation and mislead them to think that commercialising heritage sites is wrong,” he says.

“My friends started to care more about heritage sites as they recognise themselves as a Hongkonger and grow a stronger sense of belonging to the city.”

Yam understands that commercialisation is a must to preserve heritage sites and make them sustainable. But he thinks that the Central Market is over-commercialised.

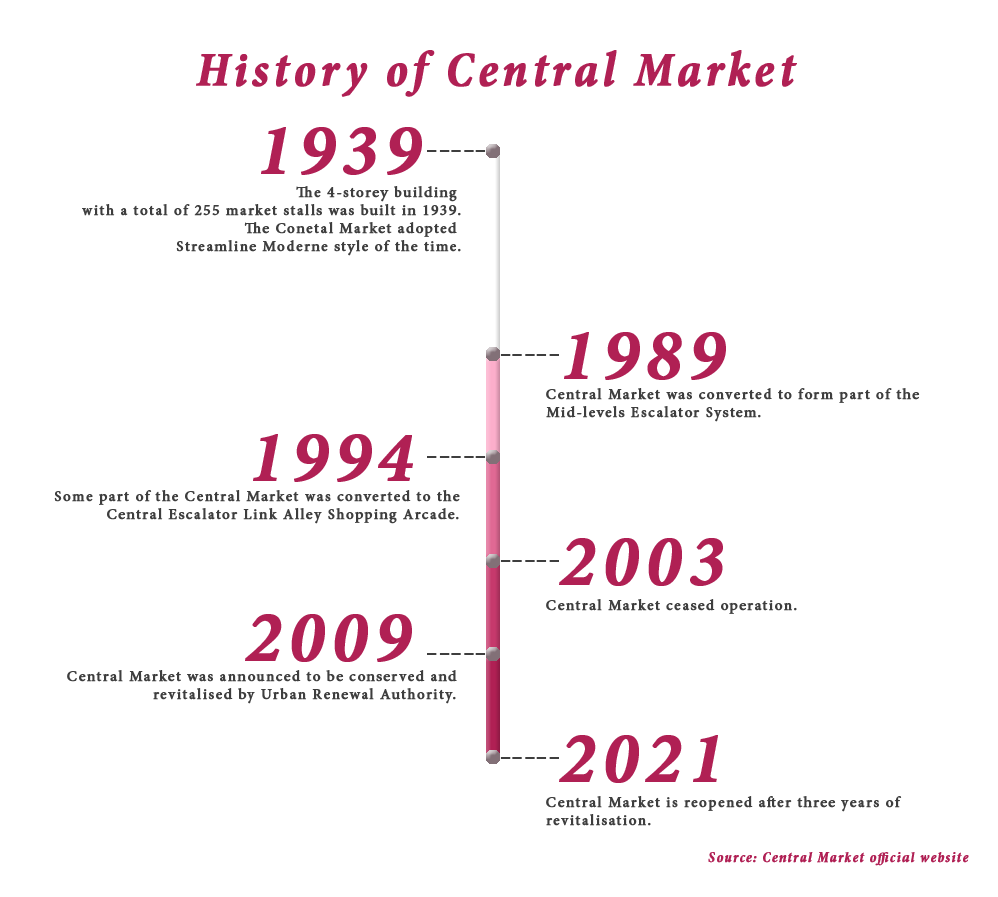

The Central Market is a government-owned Grade 3 historic building. As one of the oldest wet markets, the 82-year-old building used to be a vibrant place for residents nearby to buy groceries and build a local network until 2003.

In 2009, the Central Market was announced to be revitalised as a response to the Chief Executive’s Policy Address.

After three years of revitalisation by the Urban Renewal Authority (URA), the building with the long-standing history re-opened in August 2021 and will be operated by Chinachem Group for 10 years.

“Most of the stalls sell high-class goods and the first public activity at the site is a science education workshop which is not related to the site’s historical or cultural value,” Yam says.

Katty Law Ngar-ning, convenor of the Central and Western Concern Group, agrees with Yam. She says the younger generation born in and after the 1980s have a strong awareness about heritage conservation, citing the protest to urge the government to conserve Central Star Ferry Pier as an example.

In 2006, the government demolished the 48-year-old Central Star Ferry Pier for the Central and Wan Chai Reclamation. Many young people protested to show their discontent.

“After this incident, young people at that time started to care more about heritage conservation. Voices about protecting historical sites grew louder and that has planted seeds of heritage conservation in the next generation,” says Law.

The concern group convenor has also been following the Central Market revitalisation project.

“The Central Market was originally planned to be sold to developers. It is preserved and protected now because of public concern,” says Law.

“The over-commercialisation of the whole site by introducing high-end stores such as bars and luxurious cake shops contradicts with the original wet market vibes of the Central Market,” she adds.

“The over-commercialisation of the whole site by introducing high-end stores such as bars and luxurious cake shops contradicts with the original wet market vibes of the Central Market.”

“It is sad to see that many special features are removed after the revitalisation. For instance, handrails are added to the signature staircases and the windows near Des Voeux Road are removed and replaced by glass walls,” she says.

Wilfred Au Chun-ho, Director (Planning and Design) of the URA, shares a different concern. He thinks that it is difficult to strike a balance between different concerns for the Central Market project.

“We have spent three years collecting views from more than 10,000 citizens and professionals. The study finding shows the public wants to preserve the historical features of the structure instead of commercialising the site,” he says.

Au and his team also faced safety constraints in the project.

“The site was built in 1939 and extra measures and facilities have to be added to ensure that it is safe for people to enjoy the site,” he says.

“The URA also hopes to suggest new placemaking ideas and connect the Central Market with other heritage sites like Tai Kwun and PMQ to build a ‘cultural triangle’ in the Central and Western District,” he adds.

Lee Ho-yin, associate professor of Architectural Conservation at the University of Hong Kong, says that public awareness about heritage conservation has grown stronger as developments in Hong Kong matured.

“No one cared about heritage conservation, and everyone was busy making a living in the 1970s. People who were born in the 1980s were the first generation who grew up in a mature society and started to care more about culture and heritage conservation,” he says.

Lee points out that it is an outdated and unsustainable common belief that preserving a site entirely is the best way of conservation.

“As a lot of early conservation theories are borrowed from archaeology and museology, people from older generation follow these theories and are dissatisfied about the URA for being unable to entirely preserve the site’s outlook,” the architectural conservation professor says.

“I think preservation is a way to make a heritage site sustainable and fulfil a certain function in the community rather than a goal. The revitalised Central Market serves the community by providing space for locals and avoiding competition with a nearby wet market at Graham Street,” he adds.

“More importantly the site supports young entrepreneurs. The site not only provides stalls with cheaper rent but also teaches young people about how to run and sustain their business,” says Lee.

Lee also thinks that property developers and the public should do more.

“The property developers should spend their money on heritage conservation as a redistribution of their wealth to the citizens. The citizens should also actively urge property developers and the government to preserve heritage sites,” he says.

“People who were born in the 1980s were the first generation who grew up in a mature society and started to care more about culture and heritage conservation.”

Edited by Soweon Park

Sub-edited by Lynne Rao