Virtual idol industry is booming in China, attracting millions of fans who chat and play with their idols online

By Ella Lang

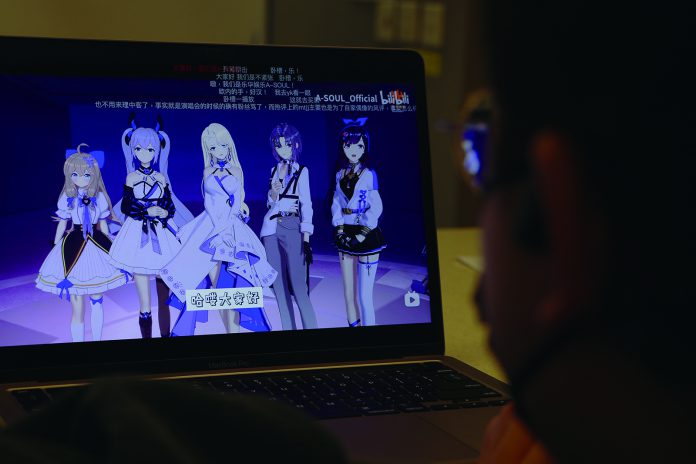

Li Jingyuan became a fan of A-SOUL this April, after accidentally clicking into their live streaming channel on BiliBili, a Chinese video-sharing platform. “It was interesting to watch their live streaming,” Li says.

“They read fans’ live comments, chat with fans, and play games designed for interaction with fans when live streaming. I feel like I am a close friend of theirs,” the Year Two university student says.

Debuted on December 11, 2020, A-SOUL is a virtual girl group created by Yuehua Entertainment and technologically assisted by ByteDance. The group has five members, who are Ava, Bella, Carol, Diana, and Eileen.

The virtual girl group has 288,000 fans on BiliBili. Their latest single Super Sensitive was released on May 1, 2021,and it received over 4 million views and 156,000 likes on BiliBili as of December 6, 2021.

Though Li is a student with no income, he has spent approximately RMB ¥1,500 (US $235) from his pocket money on buying animation merchandises including a fan-made doll and virtual presents on BiliBili.

Recognising himself as an animation, comics, and games (ACG) lover, Li pays very little attention to real Chinese stars. He says A-SOUL is his first and only idol.

“If A-SOUL were real human beings, I probably would not have become their fan,” Li says.

“Real idols’ fan groups are too alienating. For example, raising funds through personal channels, voting from day to night, and battling with other fan groups. And here comes the Qinglang campaign to regulate them. I feel lucky to be in a harmonious and peaceful fan community,” he adds.

The Qinglang campaign was introduced by the Cyberspace Administration of China in June to regulate “chaotic” online fan club activities.

Apart from A-SOUL, a new wave of China-born virtual stars is emerging, such as Yousa from BiliBili or Xing Tong (星瞳), a virtual idol from Tencent.

Virtual idols can be roughly divided into two categories, both using avatars as performance fronts. One is a virtual singer, represented by Luo Tianyi (洛天依) and Hatsune Miku (初音未來). Their vocals are synthesised using Yamaha’s Vocaloid, a voice synthesiser software, which allows users to pay for voice database and compose songs.

The other type is a virtual Youtuber or virtual live streamer like A-SOUL. Behind the virtual idol, there is a real human actor who never shows up on camera. By using motion capture technology or software, the actor’s movements and expressions are reflected on the virtual image.

The scale of the virtual idol industry in China increased 70.3 per cent year on year to RMB ¥3.46 billion (US $540 million) in 2020. It is predicted to reach RMB ¥6.22 billion (US $970 million) this year, according to Chinese data mining and analysis platform iiMedia Research.

Love across Screens

Alex Guo became a fan of A-SOUL after watching its member Diana’s birthday live streaming on March 7, which was his first click on A-SOUL’s live channel.

“I was impressed by the heart-to-heart communication between Diana and fans. I became her fan when she read letters from fans and shed tears,” Guo says.

So far, Guo has spent RMB ¥1,000 (US $156) on buying animation merchandises and virtual presents. He uploaded A-SOUL’s spoof videos on BiliBili in June and August 2021, which attracted 970,000 total views as of December 7, 2021.

“In fact, A-SOUL’s appearance,vocal and dance skills are not outstanding compared to other virtual Youtubers. But they continue to improve. I am glad to witness their progress,” Guo says.

In the fan group, some fans produce songs for virtual singers. Steven Tan, a fan of the first Mandarin-speaking virtual singer Luo Tianyi, is one of them.

“As a composer with no reputation and not enough budget, it was difficult to find a singer for my compositions. So I thought virtual singer was a good choice,” he says.

Tan bought three virtual singers’ vocal databases, each at a price of around RMB ¥500 (US $79). He composed 36 songs and released five albums. All songs were sung by virtual singers.

“I think virtual singers can overcome the limitations of real singers. Virtual singers never get tired, and they can reach a very high pitch,” Tan says.

“A virtual singer can sing thousands of songs in a month because its vocal database is accessible to anyone who pays. But it may take months for a real singer to release one song,” he adds.

“I think virtual singers can overcome the limitations of real singers. Virtual singers never get tired, and they can reach a very high pitch,” Tan says.

Still a Long Way to Go

Anthony Fung Ying-him, professor of the School of Journalism and Communication at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, thinks virtual idols in China have a bright future.

“The Qinglang Campaign influences real stars by measures such as shutting down accounts and cracking down on fan activities, but it will not affect virtual idols and their fans. This helps the virtual idol industry to grow,” he says.

Fung points out that the core attraction of virtual idols is the interaction between fans and idols. “Virtual idol fans can chat, play games with, and produce content for their idols. It is almost impossible for real idol fans to approach their idols,” he says.

“But there is still a long way to go for virtual idols to replace real idols. It is hard for virtual idols to reach diverse groups of people because it is essentially a kind of subculture,” Fung adds.

Edited by Eve Lee

Edited by Eve Lee

Sub-edited by Lynne Rao