Freelance dancers in Hong Kong risk their lives performing on stage.

By Cynthia Chan

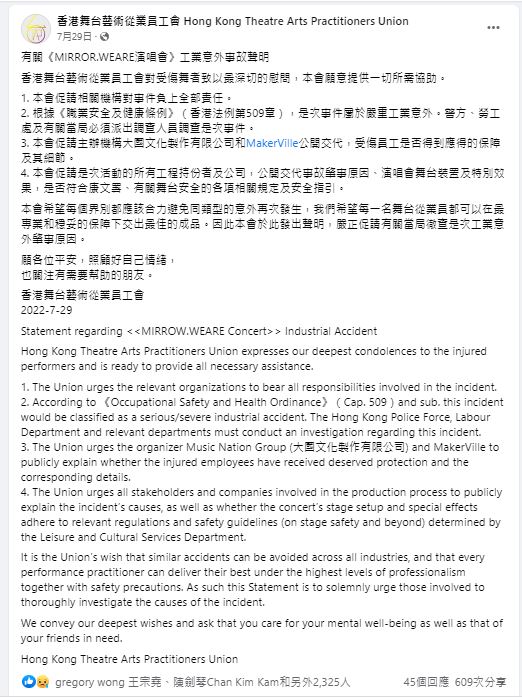

Dancers’ safety on stage has been the talk of the town after a dancer was critically injured when a giant LED screen fell during a July concert by boy band Mirror.

But accidents are not unusual according to Wong Ka-lam*, who was one of the dancers at the concert.

The freelance dancer says he was nearly injured in a stage rehearsal for a commercial dance show when stage fireworks were launched out from a device next to him years ago. But the 23-year-old forced himself to stay calm and kept the show going.

“I also saw many nails scattered around on a performance stage during rehearsals. There was no one to help even if we reported those dangerous stage set-ups!” Wong says.

Dancer Mo Li Kai-yin, 27, was critically injured when a four-by-four-metre screen weighing over 500 kg fell onto the stage during Mirror’s concert at the Hong Kong Coliseum on July 28 this year.

Li has since been hospitalised and is at risk of being paralysed as 95 per cent of his neck spinal nerve may not be able to recover fully. He can speak but cannot move or eat or drink properly at the moment.

The use of a substandard cable, poor installation and misstating the weight of devices were found to be the main causes of the accident, according to an investigation report on the concert accident released by an interdepartmental task force led by the Leisure and Cultural Services Department on November 11.

The report stated the weight of the display screens was understated 2.7 times by the production contractor.

Wong says it is common that organisers take no corresponding action even when dancers report dangerous stage set-ups to them.

The Labour Department stated on November 11 that Li was hired as an employee, but the employer did not report his work injury nor buy insurance for him. The department is considering prosecuting the employer.

Meanwhile, concert organisers MakerVille and Music Nation Group replied to the media’s enquiries that they have bought insurance for all performers. They promised to “pay for the medical expenditure of injured dancers and provide them with other support”, according to a joint statement released by the two companies on October 7.

Wong points out dancers’ safety and protection have never been the concern of any people.

“I do not know any policy that can protect freelance dancers’ rights. It is a common practice for us to make job arrangements solely by verbal agreement,” Wong says.

Without a signed contract, dancers might be classified as self-employed persons by law and are not entitled to any protection for wage, insurance or leaves.

“Companies do not cover our medical expenses, so we pay it ourselves,” Wong adds.

Wong has been performing in commercial shows and teaching dance classes for almost three years. Before being a full-time dancer, he used to attend dancing lessons for more than 15 hours a week as a university student.

Despite all his hard work, he only makes about HK$7,000 (US$892) a month as a dance tutor and a show performer, which is less than half of Hong Kong’s median income at HK$17,500 (US$2,230) due to strong competition for jobs in the industry.

Another freelance dancer, 26-year-old Tang Wai-ki*, says salaries of dancers have not changed over the past 10 years. For each night of performance, a dancer earns around HK$4,000 (US$510). They get no pay for the time they spend on dance learning, extra practicing and stage rehearsal.

She explains that the supply of dancers–from secondary students to middle-aged professionals–is abundant, and the younger ones are willing to accept lower wages.

Apart from dancing techniques, Tang says dancers have to make their own costumes, do make-ups, and design stage lighting and stage formation. They are expected to be a “one-man band”.

But they rarely demand better treatment.

“We do not want others to regard us as ‘troublemakers’, because it affects our career prospects,” Tang says, which also explains why most dancers refuse to reveal their identity in interviews.

Limited Help

Libby Cheung Wai-ting, Secretary of the Hong Kong Theatre Practitioners’ Union, says many dancers in Hong Kong know little about their labour rights.

The union helps dancers to voice out their needs to the government. They have around 200 professional dancers as members and each pays an annual membership fee of HK$250 (US$32).

“There are no corresponding policies to protect freelance dancers’ rights… as no one treats dancing as a proper career,” Cheung says.

Hong Kong dancers are often regarded as stage props serving the stars of the show, she adds.

Cheung says there are no existing safety guidelines on stage set-ups and electricity use in venues to safeguard performers.

The July accident shocked many Hongkongers and safety concerns for dancers has been lifted, but Cheung believes change may not come soon.

“Hong Kong people are good at forgetting… even though (the serious injury of Li) Mirror’s concert has raised public’s awareness, it will eventually fade away, sooner or later,” Cheung says.

A staff member from the Hong Kong Coliseum, who wishes to remain anonymous, tells Varsity that the coliseum cannot inspect every minor detail to ensure the safety of devices though contractors use low-quality materials.

The staff member adds that Hong Kong falls behind other western countries like the United States, which have established comprehensive systems and unions to protect the rights of dancers. He points out those unions negotiate fair contracts in terms of working hours and stage safety for dancers.

Gloomy future

Five people–senior employees of the main contractor Engineering Impact and subcontractor Hip Hing Loong Stage Engineering Company–were arrested on suspicion of fraud and a charge of allowing an object to fall from height in the Mirror concert. They are now released on bail.

The investigation report also suggested measures to improve stage safety, such as an increase in both the inspection of stage installations and performers’ stage rehearsal time. But no concrete actions have been taken yet.

The Labour Department advised dancers to “understand clearly the mode of cooperation and clarify whether he or she is engaged as an employee or a contractor or a self-employed person before entering into a contract”.

“Dancers who have entered into a contract of self-employment involuntarily can approach the department for assistance,” the department added.

* Names changed at the request of interviewees

Edited by Gloria Chan and Leung Pak-hei

Sub-edited by Ella Lang