Hong Kong Holocaust educator Simon Li’s lessons from the past

By Tommy Yuen

In 2006, the then Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper apologised to the country’s Chinese community for the levying of a punitive head tax on Chinese immigrants between 1885 and 1923. As he listened to Harper saying “Canada apologises” in Cantonese, Simon K. Li felt vindicated – all the reporting he had done to keep the issue in the public eye as a journalist on the social justice beat had been worthwhile.

What drove Li to persist in his journalism was his belief that the best way to arouse public awareness in seemingly uninteresting issues is to educate them. This same belief has underpinned his endeavours since he left his job at Toronto’s multicultural CHIN Radio 10 years ago. His current post is director of education at the Hong Kong Holocaust and Tolerance Centre.

Now 36, Li emigrated to Ontario in Canada with his family when he was 12. However, he first encountered the Holocaust as a primary four student in Hong Kong when he came across The Diary of Anne Frank. Even as a young child, the book made a deep impression on him but he could never have imagined back then that he would one day be a Visiting Educator of the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam.

Although Anne Frank’s words made a mark on the young Simon, it was the images from a documentary film that really seared the atrocities into his mind. The film Memory of the Camps was partly directed by Alfred Hitchcock and lay unfinished and forgotten in a vault in London’s Imperial War Museum before it was completed and broadcast in 1985. It contains harrowing footage taken in Nazi concentration camps such as Dachau, Buchenwald and Bergen-Belsen in the last days of World War II. There are scenes of scores of bodies strewn across fields, burned in huts and dumped into mass graves.

“I later realised that young kids should not watch these [images], because you really can’t sleep,” says Li.

These stories and scenes from the Holocaust stayed with Li as an adult, including when he was following and covering news of the 70th anniversary of the Nanjing Massacre in 2007. A year later, Li left Canada and returned to Hong Kong as a senior lecturer in history at Yew Chung Community College. There, he made an effort to impart knowledge about genocide and to teach his students about tolerance.

When a vacancy for director of education at the Holocaust Centre came up in 2016, Li decided to make a change and become the first ethnic Chinese to take the post. He has taken up the job at a time he thinks the field is going through a transitional period.

“From the end of the war until now, the essence of Holocaust education has been passed on by survivors telling their stories. But how can the education continue with the gradual passing away of the survivors?” he asks. It is part of Li’s responsibility to find a way forward.

To Li, genocide does not just affect the people who were killed or involved in the killings, but is an issue that concerns humanity itself. He thinks the most chilling part of the Holocaust was not the killings but the fact there were so many bystanders, those who saw what was happening but did nothing about it. “This silence of bystanders, this is something that I have found to be most shocking, from when I was a child until now,” he says with a frown.

This is why Li always emphasises the “power of one” in his Holocaust education. He says an individual’s effort can make a great difference. “You may have never considered the power of one. You may think you are the only one who is standing up, but in fact there may be more than a dozen following [in your footsteps],” he says.

Unlike in Europe and the United States, the Holocaust seems like a distant event, an abstract topic in Hong Kong and other parts of Asia. Li says there is not much knowledge or awareness of it and the sensitivities it arouses. For instance, Nazi images, decorations and toys can often be found on sale or on display, with those responsible seemingly unaware of their offensive nature.

“The Holocaust is a human catastrophe and a source of great pain to many people. When we don’t understand it, we might hurt others’ wounds,” he says.

Li thinks the language barrier is one reason for the lack of knowledge but he also acknowledges that Hong Kong is rather backward when it comes to racial sensitivity and tolerance, especially compared with Canada. As the first director of education at the Holocaust Centre to speak Cantonese and Mandarin as well as English, Li is well placed to take the story of the Holocaust and the message of tolerance to local communities, as well as to facilitate discussions in other regional centres like Taipei and Shanghai.

In recent years, Li has also worked with local schools. He says The Diary of Anne Frank is a good book to start with as it speaks to teenagers. Apart from this, another one of his preferred texts is Lilian Lee Pik-wah’s The Red String(煙花三月), which discusses comfort women and the Nanjing Massacre. Unfortunately, says Li, the history syllabus in Hong Kong’s secondary schools is so packed there is little room for in-depth discussion about the issues raised.

Outside of the classroom, Li seizes any opportunity he can to advance education on the Holocaust and other acts of genocide. For instance, he worked with Amnesty International to hold the Human Rights Documentary Film Festival, and worked on the Chinese subtitles for Watchers of the Sky, a documentary about global genocide and efforts to lobby the United Nations to adopt the Genocide Convention.

At the Holocaust and Tolerance Centre, Li is responsible for public outreach, organising a range of activities that includes talks by survivors, public exhibitions, lectures and workshops for teachers to acquire the skills to safely introduce such a heavy topic.

Many ask after Li’s well-being as he has to immerse himself in such an intense, dark subject every day. How does he deal with the emotional and mental stress? “Sometimes I think of the survivors, I do it for them,” says Li, for whom the survivors are an inspiration.

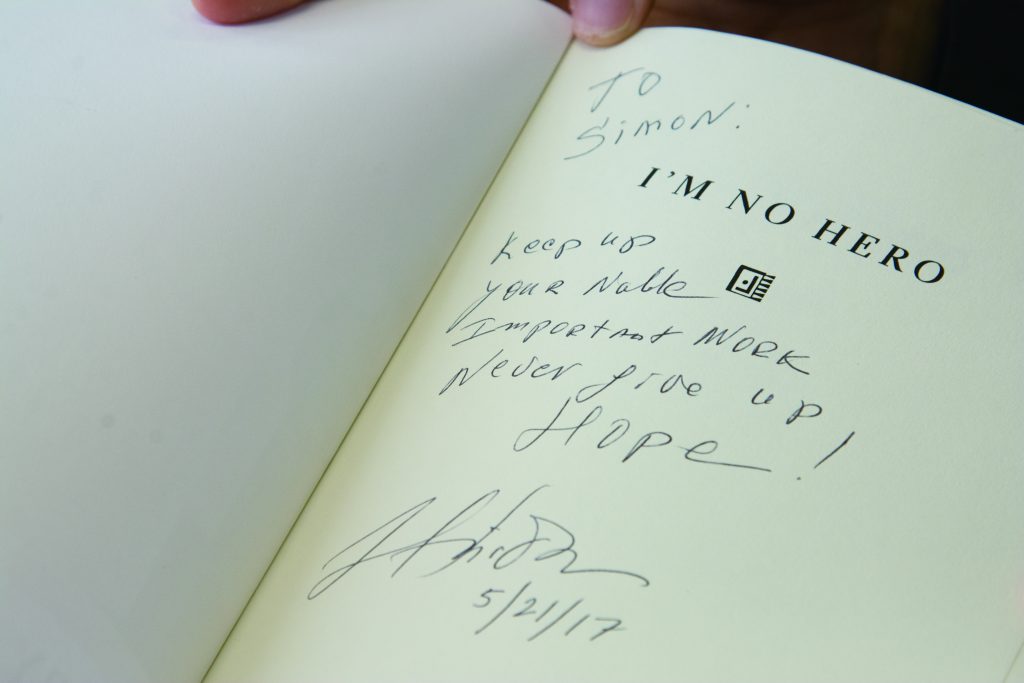

Last May, Li invited the 90 year-old Polish survivor Henry Friedman to come and give talks in Hong Kong schools. Friedman and his family escaped internment in the concentration camps after being hidden by two Ukrainian families. He spent 18 months in a tiny space the size of a queen-sized bed. Friedman later wrote a book about his wartime experiences which he called I’m No Hero, to emphasise the fact that he is an ordinary human being who survived because he was saved by others.

Like the other survivors Li has met over the years, Friedman is surprisingly humourous, Li adds. “To me he is special not only because of his experiences during the war, but also because of his hopeful attitude. He never loses hope.”

Before he left Hong Kong, Friedman gave Li a copy of his book, inscribed with the words: “To Simon, keep up your noble important work, never give up hope.” This is exactly the spirit Li wants to impart to his students.

The survivors want to bear witness, to tell the next generations about their experiences in the hope that history will not repeat itself. Li is determined to continue their mission. “We have a term called ‘never again’, that is do not [let it] happen again. However, the saddest truth is ‘never again yet again’.” As long as people do not learn from the past, education will always be paramount.

From being a journalist covering social justice issues, to teaching history in a community college, to his current role as a full-time Holocaust educator, Li says his work has remained essentially the same. “It is just a change in circumstances, but to me, my heart, my passion and my message are all the same,” he says.

His mission is to disseminate Holocaust knowledge in Hong Kong.“To talk to a witness, is to become a witness, and it is our moral responsibility to educate others,” he says.

The Holocaust was a calamity and Holocaust education is about healing wounds and preserving history so that we may learn from it. Hong Kong is fortunate not to have undergone a tragedy on the scale of the Holocaust but taking stock of the divisions and troubles in Hong Kong, Li asks us to remember this quote from the American civil rights leader Martin Luther King: “In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends.”

Edited by Jade Li