Varsity talks to one of the few Kintsugi practitioners in Hong Kong, Enders Wong, to know more about the spirit behind such artistry.

By Lambert Siu

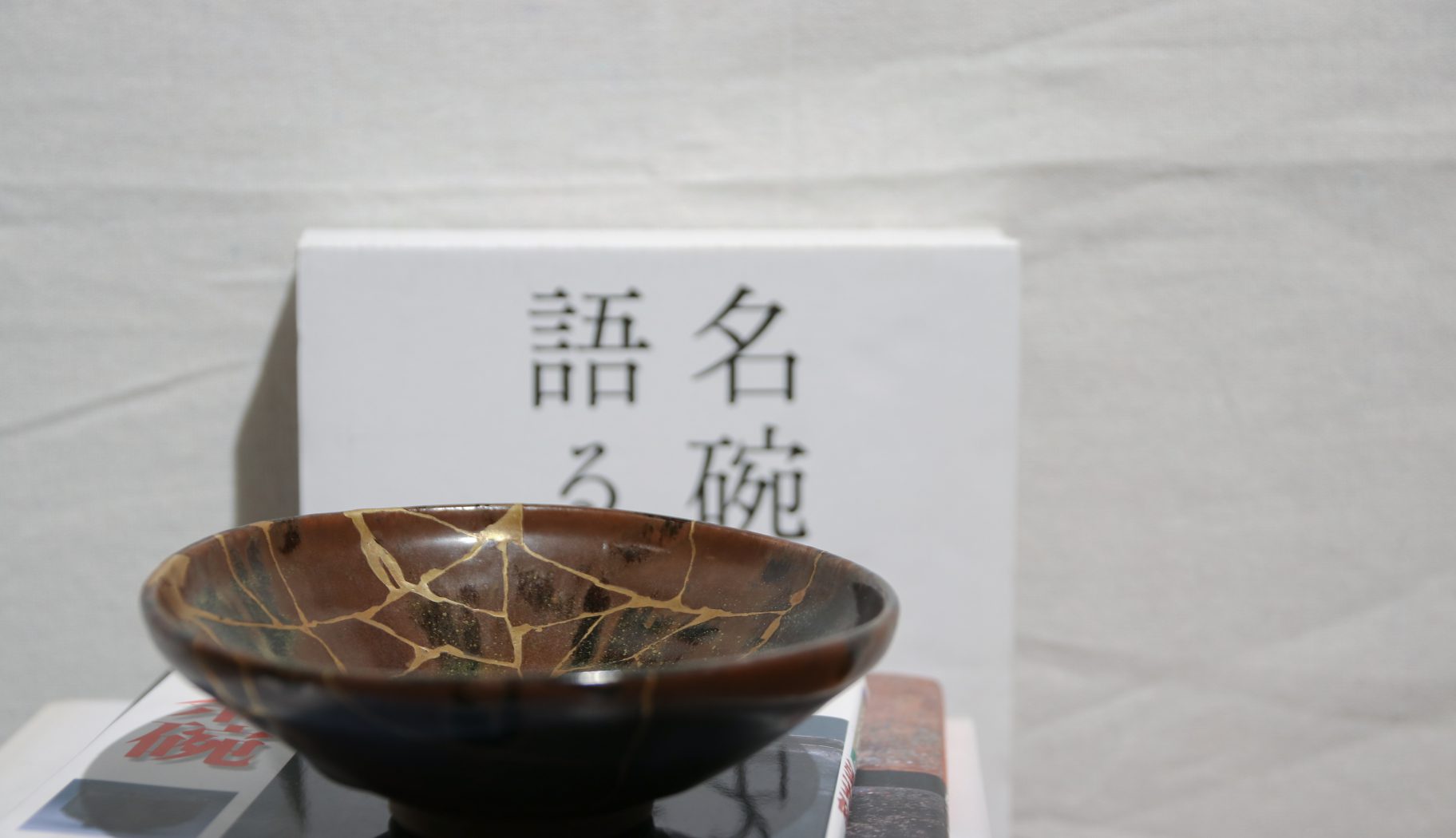

Emerged in Azuchi-Momoyama (安土桃山時代) period, Kintsugi (金繼) is a traditional Japanese repairing art that mends wreckage of ceramics with glue made from Urushi lacquer combined with water and wheat flour. The connecting joint is then coloured in gold or silver. After several centuries of development, this Japanese artistry spread to other parts of the world including Hong Kong under the promotion by Kintsugi practitioners like Enders Wong.

Wong learnt Kintsugi in Japan ten years ago and he currently organizes Kintsugi tutorial workshops in Hong Kong. Wong’s first exposure to Kintsugi was when he attempted to fix his self-made broken bowl. He then decided to visit Japan on his own as a Kintsugi apprentice, as not all materials required for the repair were available in his kits.

“Many reports available online describe Kintsugi as a mere repairing method, but it is actually an art,” he says. Wong recalls that one of his students once repaired a seemingly insignificant plate of Gudetama, a popular Japanese anime character, but it in fact carries precious memories of his parents. He thinks Kintsugi is more than just a repairing technique, since it bears unique meaning that is special to every individual who practices the skill.

Kintsugi is often interpreted as a way to restore broken objects to their original forms by reconnecting broken fragments. Yet, Wong thinks there is something more to this craftsmanship that encourages creativity. He recalls his experience of designing a whole set of tea ware specifically to fit the shape of a piece of broken glass, instead of gluing the fragment back to its main part. He cites a student of his as an example. The student used crystal to fill gaps between a broken wine cellar instead of simply colouring the crack with gold or silver, challenging the traditional boundary of Kintsugi.

Wong also draws differences between the philosophy behind Chinese and Japanese repairing. While Chinese repair things aiming at recovering functionality, Kintsugi advocates the aesthetic of wabi-sabi (侘寂) , which highlights the appreciation of imperfection and recreation from the broken. Embracing the flaws in order to survive, especially during natural disasters, has become one of the key elements manifested in this art form.

“After the March 11 tsunami tragedy in 2011, people collected broken fragments by the sea and returned them to their owners after mending them as they think it is a way to bring hope to victims by reminding them there is always a way to heal their wounds,” he explains.

Wong thinks Hong Kong should develop her own Kintsugi with a special character. “Hong Kong is Hong Kong. You have to be aware of your unique characteristics and be yourself,” he says. He also realises that some Hong Kong Kintsugi artists copy the Japanese style directly without infusing the work with their own elements. He reckons the way out is to spend more time tracing back to where they grow up from and dig out the essence of what belong to them.

“I want to create Kintsugi of Hong Kong,” he says. He believes Kintsugi in Hong Kong can bring a sense of peace to individuals as they can stay focused when mending broken objects for a few hours without any distraction.

“Amid troubled times like this, it [Kintsugi] should evoke calmness from within and lead us to have faith in the chance of rebirth,” he adds.

It may seem unrealistic to talk about Kintsugi in Hong Kong right now, as protests continue. But Wong sees it in a different way. To him, Kintsugi is a line that joins the past and future together. Through Kintsugi, a broken past is repaired and metamorphoses into a new form of future.

Edited by Scarlet Shiu