Fishermen in Bohai Bay are struggling with sharp decline in harvests and impact of COVID-19.

By Laurissa Liu in Tianjin

Fishermen hope a four-month moratorium from May to September can help Bohai Bay revitalize its vitality and bring them rich fish harvests.

But desertification of ocean floor and the impact from COVID-19 shows no mercy to the fishermen.

Liu Dongxiang, a fisherman with over 30 years of experience in fishing in Beitang is one of them.

Liu and his family keep casting and collecting fishing nets overnight every day, starting from September.

“The hunting usually starts from mid-night or after dinner,” Liu says. “We then have to sell our harvest during day time. Our work never stops,” he adds.

Throwing out fishing nets and waiting under starlit night is a fisherman’s usual routine. By the time they get back, diners flock to the dock to buy lively seafood lifted from the ocean.

River crab, swimming crab, mantis shrimp and various shellfish are the most commonly seen and popular seafood among customers in Bohai Bay market.

Liu’s family relies on fishing to make a living. Yet in recent years, harvests have dropped drastically, because of the serious ocean pollution and overfishing. Sharp decline in fish harvest affects all fishermen in Bohai Bay.

“The catch has declined rapidly from 200-300 catties (100-150 kg) a day to only 20 to 30 catties (10-15 kg) in the past two years,” he says.

The current number of fish eggs is only half of before, compared to the data from 1982 to 1983, according to a research released by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs in 2018. The seafood resources are less than one tenth of the time.

The Bohai Bay is one of the four traditional fisheries in China. Tens of thousands of fishermen in Tianjin, Hebei, Shandong, and Liaoning make their living at the bay. But the shallow bay is overwhelmed by large-scale commercial fishing.

The government introduced the four-month fishing moratorium in 1995 to protect the marine ecology, considering the situation.

“No matter how fast fish and shrimp grow, boats are always faster. No matter how many fish are released, there are always fishermen in boats waiting to capture them,” Liu says.

September is the best season for harvesting mantis shrimp. Abundant yield of mantis shrimp used to be a major source of fishermen’s income. But harvest has dropped significantly this year.

“The harvest weights 2,000 catties (1000 kg) for a single boat trip in 2000. Yet, the harvest drops to around 500 catties (250 kg) this year,” says fishermen Han Gui, who is also based in Beitang.

“Mantis shrimp is the most popular seafood here, and the growth can never match the demand,” she adds.

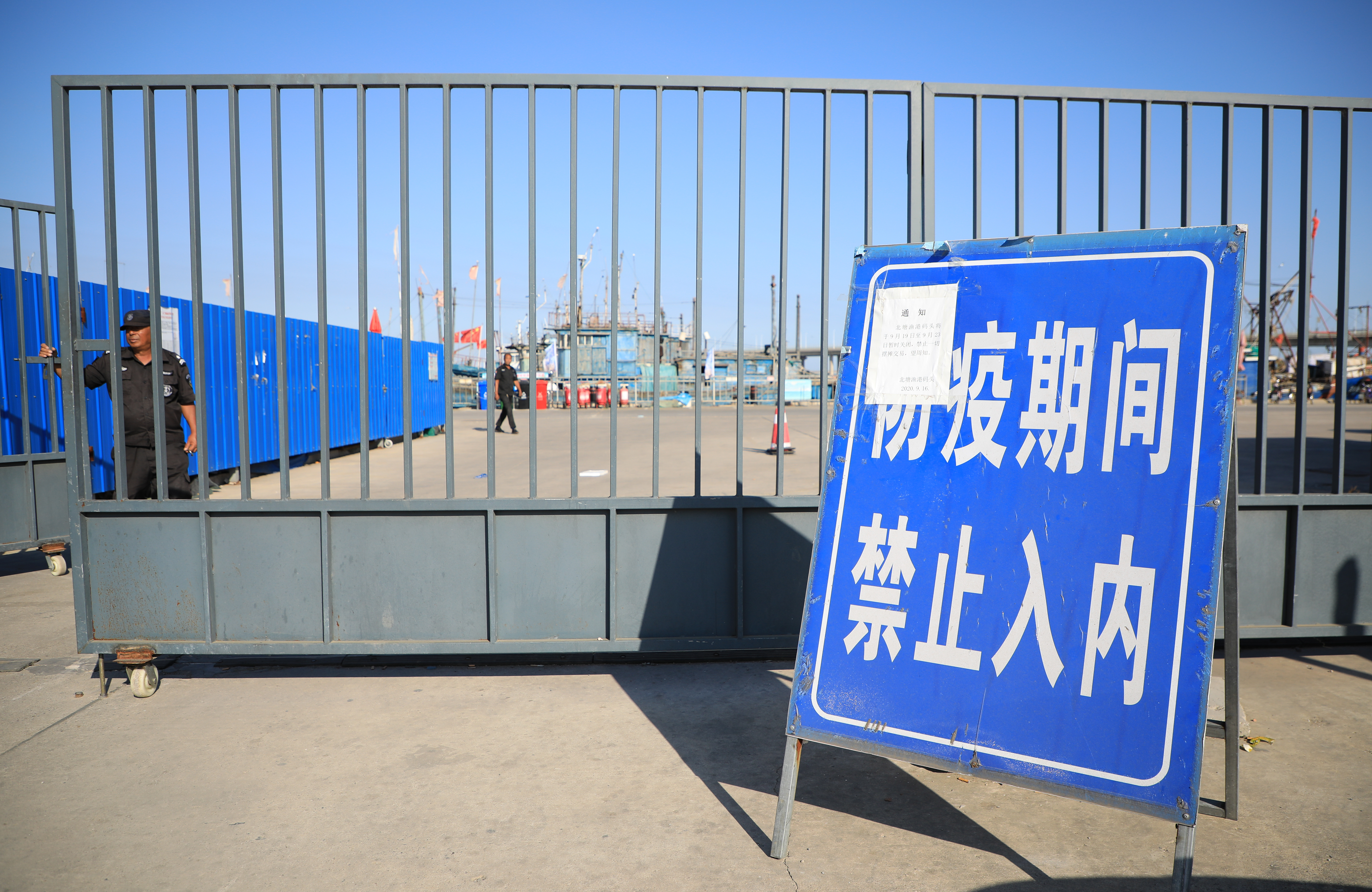

Apart from sharp decline in harvest, the pandemic also makes it more difficult for fishermen to make a living.

The fishermen can only rely on government subsidy during the summer moratorium. Some young fishermen used to look for part-time jobs in service and construction industry. But it was not easy to find work during the pandemic.

Liu’s son, 24, used to work full-time in a restaurant, lost his job in March and rejoined his family to do fishing. “Fishing doesn’t make as much money as working in a restaurant,” he says. Fishing trips for tourists are also cancelled due to the pandemic.

“We only have local buyers. Tourists from other parts of the country have stopped visiting, especially those from Beijing,” Han says.

It takes only two hours to travel from Beijing to Bohai.

The pandemic has also affected the seafood market business. “The wholesale price of crabs has doubled. The price is RMB ¥60 (US $9) to RMB ¥70 (US $10) per catty (0.5 kg),” says Han Yongqing, a seafood vendor market and a former fisherman. “Demand for seasonal seafood after the pandemic jumps, but the supply can never catch up with it.”

“Catching octopus used to mean bad luck. But now fishermen want anything that can be sold for money,” Han adds.

Edited by Lasley Lui, Regina Chen