Audio-only app Clubhouse saw an influx of mainland Chinese users bypassing the Great Firewall for censor-free discussions with people worldwide in Feb 2020, before authorities banned it within one week.

By Ryan Li

Avery Guo* joined a Clubhouse chatroom for the first time after she downloaded the application for online audio chatting on February 7, 2021.

When a chatroom moderator called out her name, Guo turned on her microphone and shared her thoughts about China’s education policy for ethnic minorities which gives ethnic minority students extra credits in Gaokao, the country’s college entrance examination.

“I said that ethnic minority students didn’t really benefit from the policy and that ethnic minorities in China should be encouraged to speak their own languages instead of being forced to learn Putonghua,” the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) student recalls her first Clubhouse sharing with over a thousand audience members.

Guo received an invitation from her friend on February 6 to join the Clubhouse community. She then started exploring chatrooms discussing China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

“Clubhouse indeed has broadened my horizons. I learned about some Chinese social activists, like Ai Weiwei, for the very first time. It also is a rare platform in China where people holding different views can discuss with each other peacefully,” she says.

“It also is a rare platform in China where people holding different views can discuss with each other peacefully.”

Clubhouse, launched in April 2020 by IT company Alpha Exploration Corporation in San Francisco, has gained worldwide popularity since the first few days of February 2021.

Users are given opportunities to explore audio-only chatrooms on Clubhouse. In these rooms, people talk with each other through a conference call, with audience members listening quietly. Users can freely enter and leave the chatroom or raise their hands to speak whenever they want.

For its users in China, the application has provided a chance for them to freely discuss political issues without censorship.

But Guo noticed some changes on February 8.

“Fewer voices from mainland China could be heard, and topics switched from sensitive political issues to love affairs and investments,” she says.

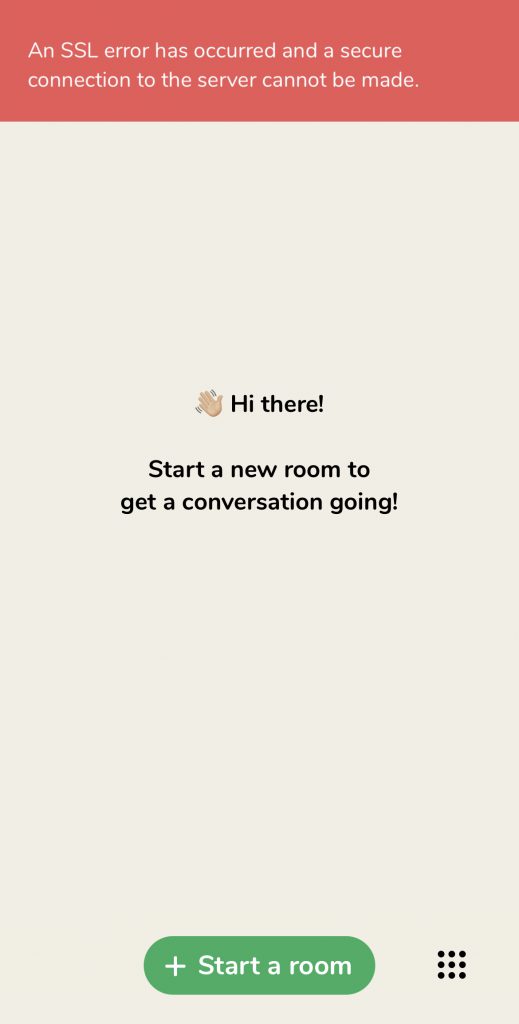

Clubhouse was banned in mainland China in the afternoon of February 8, with a red banner popping up when opening the application saying that “a secure connection to the server cannot be made”.

Chinese users now have to bypass China’s Great Firewall with the help of a virtual private network (VPN) service, which is considered illegal by Chinese authorities, in order to use the app.

The Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin said China “is firmly determined in safeguarding national sovereignty, security and development interests and rejecting foreign interference”, when responding to questions from a foreign reporter about the ban at a press conference on February 9.

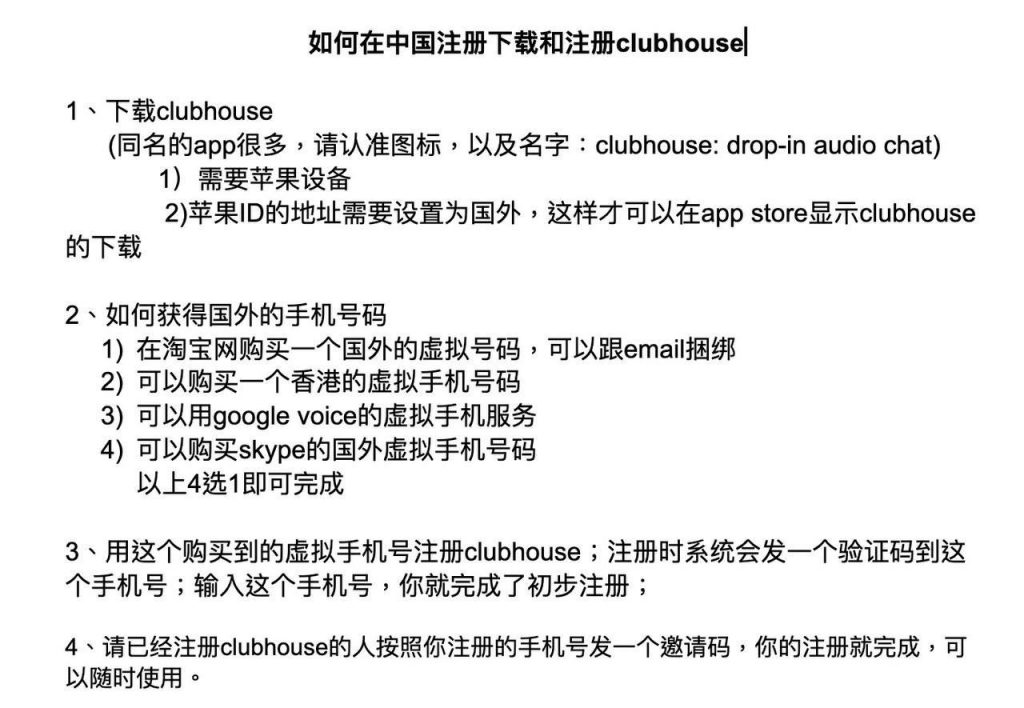

(Shared among Chinese netizens)

But not all join Clubhouse to talk about topics considered to be sensitive in China such as political issues in Tibet, Xinjiang and Taiwan.

Jessica Hua* works for an online game company in Shanghai. She received an invitation to use the app from her colleague on February 4.

“People in our industry by nature pay attention to new products like Clubhouse and new trends in the trade,” Hua says.

“People in our industry by nature pay attention to new products like Clubhouse and new trends in the trade.”

Elon Musk, the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Tesla, was interviewed by the Good Time Show in a Clubhouse chatroom, discussing topics from when people can travel to Mars through SpaceX’s programme, to his view on digitalisation of the medicine industry, on February 1.

“I think (Clubhouse) is a place where elites from various industries network with each other. Sharing sessions with CEOs and company founders flood my homepage,” Hua says.

The 25-year-old now uses Clubhouse less often, partly because of the decreasing number of users from China after the ban.

Mobile phone users in China can no longer be invited to use Clubhouse after the ban was imposed on February 8, as they cannot receive the verification code sent to their phones through Short Message System (SMS) during registration, even if they use VPN.

“Room for discussion has been limited after (the ban). It’s hard to explore new topics with a limited number of active users,” Hua says.

“Room for discussion has been limited after (the ban). It’s hard to explore new topics with a limited number of active users.”

Simulating the user interface and basic functions of Clubhouse, Duihuaba (對話吧) was launched by a Chinese Livestream company Inke (映客) on February 11. Several other companies are also developing similar platforms in mainland China.

Domestic replicas of some applications banned in China have been prospering in China. Two examples are Twitter-like Weibo and YouTube-like Bilibili, which have become mainstream social media platforms in mainland China.

Cyberspace Administration of China said in a notice on March 18 that it has summoned staff from 11 internet companies, including Inke, Tencent and Alibaba, to meetings to evaluate the security of audio-based social media platforms.

Fang Kecheng, associate professor of journalism and communication at CUHK, doubts if these Chinese versions can function like Clubhouse, as he says what made the discussions on Clubhouse special was not about “knowing” but “listening”.

“The essence of the original version lies in its users, and how they connect with each other,” Fang says. He describes the period before Clubhouse was banned, which is around the first quarter of February, as “rare”, because mainland Chinese users could enjoy the freedom of expression without censorship at that time.

“Users (in mainland China) could directly listen to Taiwanese people, Uyghurs and witnesses of protests in Tiananmen Square in Clubhouse. This sense of intimacy can hardly be felt when reading news reports,” he says.

Looking to the future, Fang thinks that the story of Clubhouse in China is nearly over.

“It’s possible that Chinese intellectuals and cultural elites may continue to engage in cross-cultural and cross-regional discussions, but it can hardly have a great impact on the masses,” he adds.

But Fang stresses that although free access to Clubhouse was cut off fast, “We can still see it from an optimistic point of view. It shows that as long as an opportunity comes and a suitable platform can operate, conversations like those in Clubhouse are still possible, no matter how many misunderstandings we’ve had with people holding different views before,” he says.

The Constitution of the People’s Republic of China declares that its citizens enjoy the freedom of speech. But in practice, overseas social media platforms including Twitter, Instagram, Facebook and Clubhouse are blocked in mainland China.

“China’s ban on certain platforms is not reasonable. (The country’s) policy on speech control has been tighter than before,” says Tomoko Ako, a professor from the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of the University of Tokyo. “I personally believe that freedom of speech is very important for human beings,” she adds.

Ako, who specialises in Sociology and China Studies, lived in Beijing from 2001 to 2003. She recalls there were more citizen-initiated movements at that time.

“Social media was used to put pressure on local governments or officials, as well as to collaborate with investigative journalists or scholars to solve social issues at that time,” Ako says.

“But nowadays it’s very difficult for these citizen groups to mobilise the public,” she adds.

For Chinese users on Clubhouse, the Japanese academic thinks Clubhouse’s most important impact on them is that they have a chance to “look outside the wall”.

Ako believes China’s Great Firewall, to a certain extent, resembles the intangible walls erected by individuals in daily life due to religion and nationality differences. She thinks “everyone has a wall around, and we have to get over it” to mutually understand each other.

“Ideally speaking, if you can go freely between differences, then you can see different worlds and expand your perspectives,” she says.

Ako thinks China will be a superpower in the world, and she has two possible scenarios in mind.

“From a pessimistic view, China will tighten its control on domestic speech, unwilling to communicate with democratic countries,” she says.

“From a pessimistic view, China will tighten its control on domestic speech, unwilling to communicate with democratic countries.”

“I am sometimes very critical to (China’s) policies. But I really hope China can be more open, transparent and democratic,” says Ako, referring to her optimistic view of the country, in which it will try to participate in international dialogues and take its role as a “responsible leader”.

* Names changed at interviewees’ request.

Edited by Laurissa Liu

Sub-edited by Patricia Ricafort