Verochod Punthong promotes Mon culture in Thailand through his museum, research, and a historical book to revive Mon heritage.

By Nutcha Hunsanimitkul

For more than 30 years, Verochod Punthong has been trying to let more people learn the history and culture of Mon, an ethnic minority in Thailand that contributes to the history of Southeast Asian countries but has been neglected.

Mon was welcomed by the Thai Monarchy to emigrate and settle down around the central part of Thailand for 200 years. Its customs have been embedded in Thai culture which can be seen in Buddhism, traditional musical instruments, housing style, and even the world-famous cuisine of Thailand.

“Mon brings us these proud cultures. Food like Khao Chae and Karyasand, or musical instruments such as Peepat Mon and Korng Mon are Mon cultures that most native Thai can be related to. But when it comes to Mon history, they barely recognize it,” the half-Thai-half-Mon says.

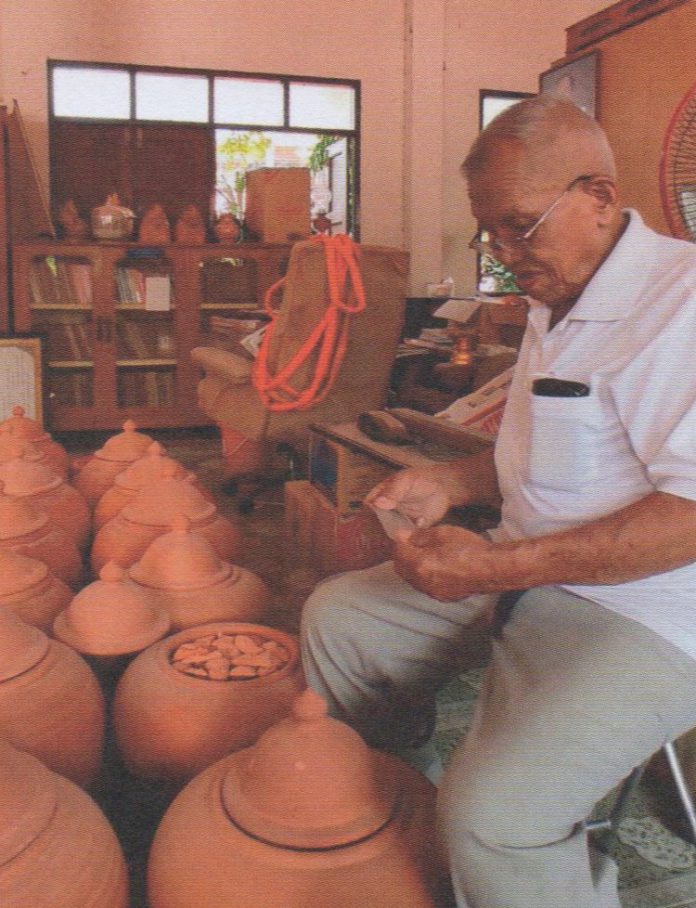

(Photo courtesy of Verochod Punthong)

Punthong, 86, is now running the Chompoo Wek Temple Local Museum (พิพิธภัณฑ์พื้นบ้านวัดชมภูเวก) with the hope to shed light on the Mon culture.

(Photo courtesy of Verochod Punthong)

“Thai historical scholars and Sukhothai University advised me to build the museum and display all Mon folk equipment including cooking tools, clothing, and Buddha statues I found in the temple so it would not be lost and people can come to learn about it,” he says.

He believes those artifacts are messages from the past to young generations to appreciate their origin more.

“A few bricks from religious architectural ruins can tell us much information about the ages of Mon heritage and its strong relation with Buddhism.”

“All artifacts tell who we are and where we are from. I believe this museum can promote a realization of Mon history and pass down these precious memories to the next generation,” he says.

(Photo courtesy of Verochod Punthong)

The first call for his own origin

Restoring the worn-out Chompoo Wek Temple in Central Thailand about 20 years ago was the first calling for Punthong to trace his roots.

“My brother was the abbot of the temple at that time. It was really old and unstable that the monks could not live there. It was not about what I was supposed to do but it was a must, otherwise, it would collapse, ” he says.

Retired from his job as an engineer, he devoted all his time supervising the restoration of the temple. He became more appreciative of the Mon culture and hoped more people would also know more about it.

“Mon is a treasure of our community.”

Sharing some sweet memories of his dating life, Punthong reminds his close bond with Mon culture.

“I rowed a wherry along the river to meet my wife when we were young. She also loves to cook Kang Matand, a Mon traditional dish, for our family, ” he says with a smile.

Transportation by a wherry and a connecting livelihood with the river is one of the Mon cultures that is hardly seen in Thailand now.

Through years of extensive research about Mon history, Punthong has gathered a great amount of evidence that Mon is more than a root of Thai culture but the main force fighting for Thailand in various wars throughout the history of Thailand.

“The scale of the Thai army was really small at the time. Mon people joined the Thai military and helped fight against enemies. Without them, Thailand would not have come this far. It is sad to see these memories of the Mon getting lost in our generation,” he explains.

Last gift for the youth

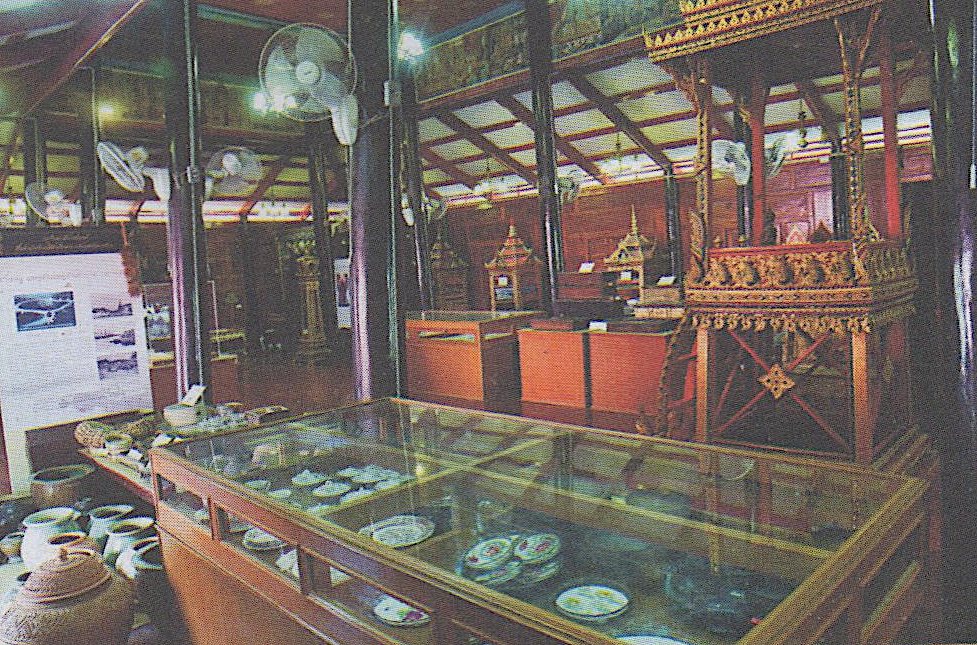

The local museum has attracted local schools and tourists from different parts of Thailand to learn about Mon. It also collaborated with the Department of Tourism of Thailand as a tourist attraction spot.

(Photo courtesy of Verochod Punthong)

“I gave tours and narrations of the museum to school students and Thai-Mon communities coming from other regions of Thailand. We gained quite satisfied feedback from the public,” he says.

(Photo courtesy of Verochod Punthong)

(Photo courtesy of Verochod Punthong)

“I think it is important for them to see the value of ourselves and appreciate it more. It brings self-pride to them. But I am too old now,” he continues.

Turning 86 years old this year, Punthong’s children remind him to take care of his health. He no longer tells the many interesting stories about the Mon and walks around with students now. Without his presence, many of the activities in the museum are now suspended.

“We have more than enough volunteers to help organize the activity but none of them have the insight into Mon history, ” he says.

Worrying about fake information that devalues Mon history and fewer local children are keen on their own culture, the half-Thai-half-Mon has been devoting his time to writing a Mon historical book, which he regards as “the last gift about the Mon for the younger generation”.

“I believe people will not repeat mistakes and will become better people by learning history. I hope my book will bring pride to Mon people, ” he says.

Edited by Charmaine Choi

Sub-edited by Esme Lam