Taiwan’s leading bookstore shakes up local book scene

By Matthew Leung and Vicki Yuen

Queenie Wong Kwan-yi alternates back and forth between tip-toeing and kneeling as she scans the bookshelves in the handicrafts section. Each shelf reveals another collection of treasures. In her left hand, she holds a shopping basket containing almost a dozen books and two items of stationery.

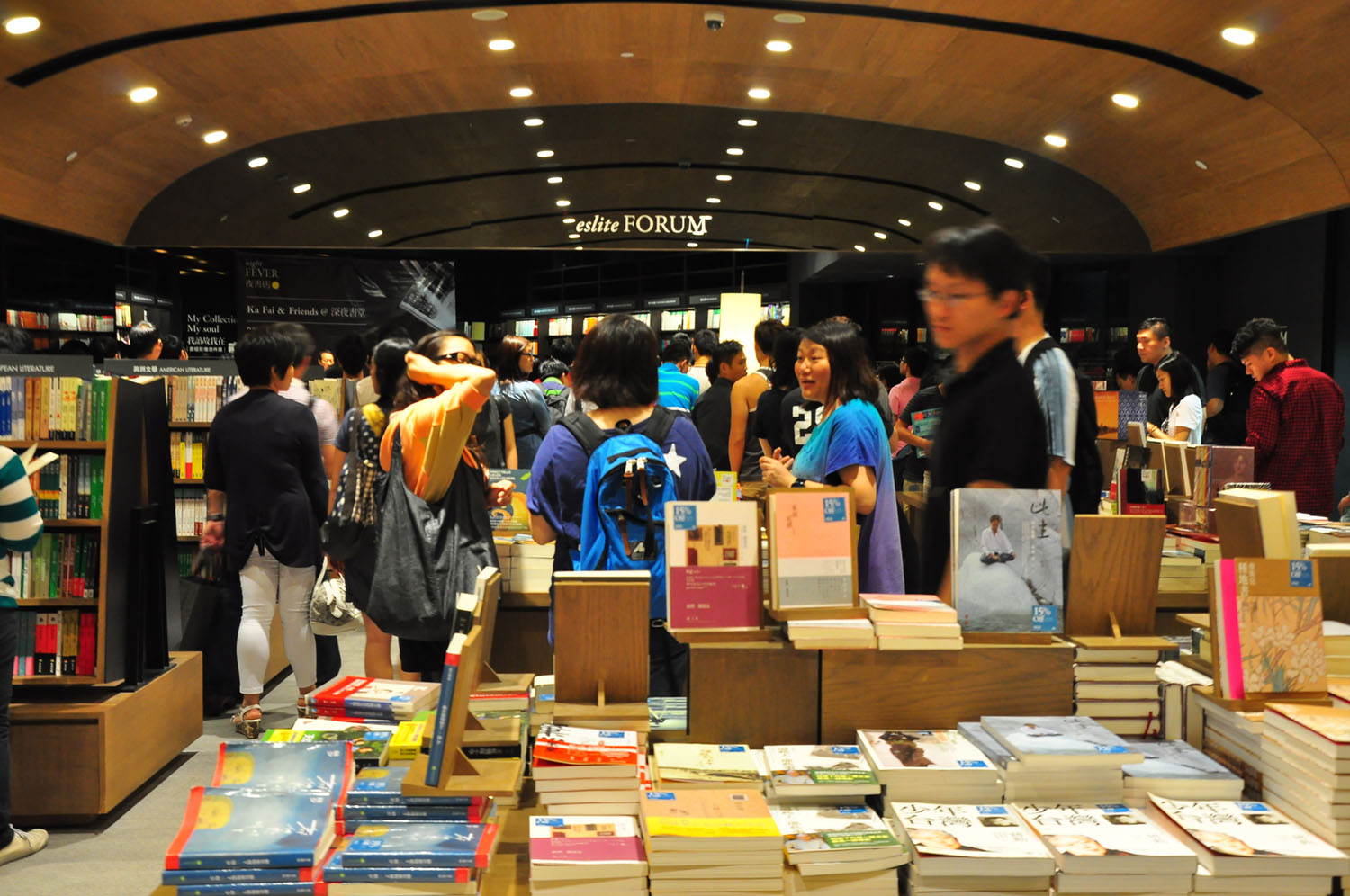

The sixteen-year-old student is a huge fan of the Eslite chain of bookstores in Taiwan, where the company was founded, and has visited them no less than five times. But this is her first visit to Eslite’s recently opened and, perhaps, the most discussed bookstore in Hong Kong.

After spending over five hours looking around, Wong is ready to give her assessment. She is impressed by the variety of books Eslite Bookstore offers, especially the handicraft books published in Japan. “I have not considered my budget, I would buy anything that I am interested in,” she says.

Eslite is one of Taiwan’s best known retail chains and has been around for 15 years. The Eslite brand of lifestyle and culture has captured the imagination of not only Taiwan readers and shoppers, but also Hong Kong and mainland visitors. Its stores, which are more like trendy shopping malls than mere bookshops, have become tourist attractions.

Around 70 per cent of the floor space is used to sell stationery and food and drinks, leaving just 30 per cent of the space for books. Book sales account for 30 per cent of company profits.

The success and popularity of Eslite Taiwan means there are high expectations for the new store in Hysan Place, Causeway Bay. However, the business model for the Hong Kong store differs from those in Taiwan.

Under the terms of the lease of the shop, 85 per cent of the 41,000 square feet retail space has to be given over to books. There are 100,000 books in the store, 40 per cent of which are English books. Books in simplified Chinese are yet to be introduced. When the three-storey shop officially opened in August this year, Eslite fever swept the city and there was much discussion of the impact it could have on Hong Kong’s reading culture.