Taiwan’s cafes and bookstores host a vibrant salon culture that played an important part in the development of the island’s democracy and as Varsity discovers, continues to provide a platform for debate today

By Victor Chan and Nia Tam

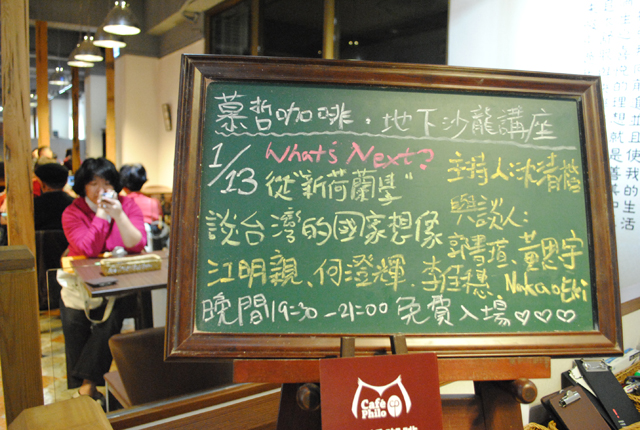

On a Friday night before the day of Taiwan’s presidential election, customers at a café in Taipei sipped their coffee and read books. In the basement space below them, around 50 people gathered to discuss what Taiwan could learn from its past colonial masters, the Dutch.

As they hotly debated issues ranging from animal welfare to language and culture, they shared their concern about Taiwan’s development. They came from different backgrounds; authors, cooks, students, workers and retirees.

Some of them were regulars at salons, places where people can exchange opinions on the issues of the day.

Raphael and Muller, both in their twenties, attend this kind of salon almost once a week. They believe public discussion helps people to understand more about their society and gain meaningful insights through rational debate.

Salon culture has played an important role in shaping Taiwan into the most democratic society in the Chinese-speaking world.

The liberal culture sprouted in the Wisteria Tea House, a Japanese-style teahouse situated in Taipei, in the 1950s. David Chow, the late owner of the teahouse, invited political dissenters to secretly criticise President Chiang Kai-shek’s dictatorship when Taiwan was still governed under martial law.

As more and more discussions about democracy and other public issues were held there, the teahouse was transformed into the archetype of the present-day salons. Now, many forums can be found in Taiwan’s cafes.

As active participants in the debates held in Wisteria Tea House and other salons, Liao Hsien-hao, professor of foreign languages and literatures at National Taiwan University, thinks salon culture helps foster social stability by providing an open platform for the general public to vent their anger towards the authorities through conversation.

Apart from cafes, salon culture in Taiwan has also spread to some independent bookstores. Mandy, who works at Fembooks, a feminist bookstore in Taipei, takes part in various talks and forums about gender and social welfare that are held in the store. She believes that when the public’s voice grows stronger and louder, it can directly influence real politics.

It is no surprise that running a cafe or a bookstore for regular public discussions is not a lucrative business. Even so, Hung Jane, who runs a cafe named Humanity Space, says she gains in other ways through the discussions. “A sense of deliberation can also be developed among the citizens by critically debating the public issues,” Hung says.

However, some other cafes and bookstores choose to deliberately distance themselves from public issues. They still offer spaces for talks about the arts and literature, but they do not describe these spaces as salons. The shopkeepers of Whose second-hand bookstores says they do not want to get involved in public or political issues. They say theirs is an alternative attitude towards salon culture.

This alternative positioning of salon culture is itself an indication of the democracy and diversity which salon culture has helped to nurture. “Salon culture is a process that the public has to experience when learning modern democracy,” says Kuang Chung-shiang, assistant professor of the department of communication at National Chung Cheng University. To Kuang, democracy can only be learnt through rational discussion and dialogues in society.