Hopes are pinned to the medical use of the technology

By Vivian Lai & Zoe So

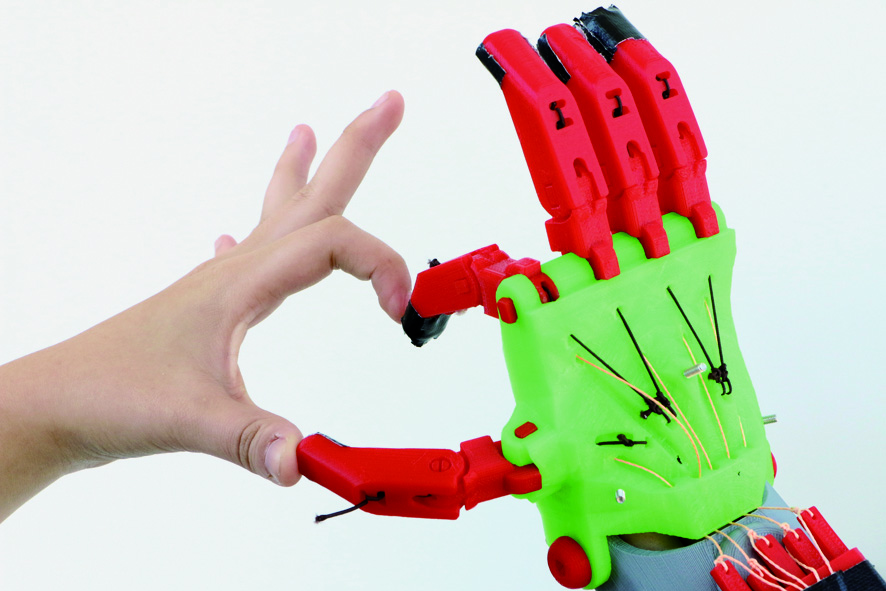

There were handicrafts and gadgets galore at the Hong Kong Mini Maker Faire where engineers, inventors and artisans showed off their creations. While many visitors gravitated towards the various robots on display, intent on their pilgrimage to find the perfect geekdom, a handful gathered in a corner of the exhibition hall. Their eyes were fixed on a 3D-printed artificial arm – a simple design, yet a cutting-edge invention – which 31-year-old participant Au Kai-chun was using to try to lift a water bottle.

Born without a left forearm, Au gave up using a traditional artificial arm after a short period of time as a child. “The traditional ones are designed to be durable and heavy, as they assume you will wear it throughout your life,’’ he says. Au has grown accustomed to life without a forearm, but when he came across the idea of a light and stylish prosthesis made by 3D printing, he decided to join a project initiated by the Maker Club as a tester.

Maker Club is a voluntary group of technophiles, operational therapists and programmers. Inspired by the US-based international network, E-nabling the Future, members decided to help customise artificial limbs using 3D printing technology.

Au explains that designing a perfect prosthesis requires making lots of adjustments. “The traditional mould-making for each adjustment can be very expensive, costing more than HK$100,000 in total … 3D printing is cheap so you can experiment and improve continuously,” he says.

A 3D printer works like a normal printing machine. First, users have to scan an object or send a design blueprint to the printer. The needle-shaped printing head then deposits liquid plastic on the base according to the design. Layer upon layer is laid down until the plastic fuses together and the product takes shape.

Mark Li, one of the organisers of Maker Club, says the cost of producing a prosthesis automated by an electric motor is around HK$2,000, whereas a mechanical one would only cost several hundred dollars to make. So far, Maker Club has helped Au kai-chun and an 8-year-old boy by designing tailor-made plastic limbs for them.

The little boy was born with just a thumb and little finger on one hand, which makes it difficult for him to hold a pen and use an eraser. The doctor says he cannot wear an artificial hand as the traditional design does not fit. “We were touched by this case and so hoped to do something to help him,” says Li whose team designed a tailor-made mechanical fist for the boy. With the mechanical fist, he can control the fingers of his prosthesis to grab objects.

3D printing may bring new hope for disabled people and amputees, as any standardised 3D printer can be used to produce a patient-specific design. However, Tse Chi-yung, a professional prosthetist and orthotist collaborating with the Maker Club, still has reservations about this application of the technology and its limitations. “Amputees can actually get hurt if the prosthetic leg breaks when they are walking,” he says, “I’d hesitate if I had to introduce it to my patients because there’s no official recognition. What if it breaks easily? When it comes to medical equipment, certification is very important!”

3D-printed artificial limbs are lighter and less durable than the traditional ones. Though they are cheap to produce, they are only expected to last for one to two years. Lifting heavy objects or accelerating suddenly could overload and break a prosthesis, leading to safety concerns. There is still a long way to go before hospitals can recognise the use of 3D-printed artificial limbs.

Although 3D printing may seem to be new and cutting-edge, the manufacturing industry has been using this technology for years, especially in the production of toys, jewellery and other small components. Compared to using traditional mould-making and die-casting to mass produce identical objects, 3D printing is more flexible, customisable and design-sensitive.

It has become better known among the general public recently because some local artists have used the technology to make sculptures and artwork, while cheaper, consumer-targeted 3D printers have enabled handicraft workshops to let people have a go at printing their own designs. The biomedical application of the technology remains less well-known and understood.