Brutal aspects of the invasions of Korea and China have been omitted in Japan’s history education about World War II.

By Charlotte Wu in Nagasaki

Edward Vickers, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Chair on Education for Peace, Social Justice, and Global Citizenship, was shocked by residents’ ignorance when he tried to find a way to the Oka Masaharu Peace Memorial Nagasaki Museum.

Staff in the tourist information at Nagasaki station had no idea about the whereabouts of the private museum covering war crimes committed by the Japanese army during World War II. Eager to help, one of the staff members was stunned when Google Maps on her phone showed the site was merely five minutes’ walk from the station.

The museum is not listed in the Nagasaki official guidebook. But the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum, a government-funded museum focusing on depicting Nagasaki’s suffering after the atomic bomb attack, is included.

“Private museums can tell whatever stories they want to tell. But as they are operating outside the public system with no government recognition, it is also challenging the mainstream story of the war. It is going to struggle to publicise itself and find itself marginalised within Japan,” says Vickers, an Asian Studies professor at Kyushu University.

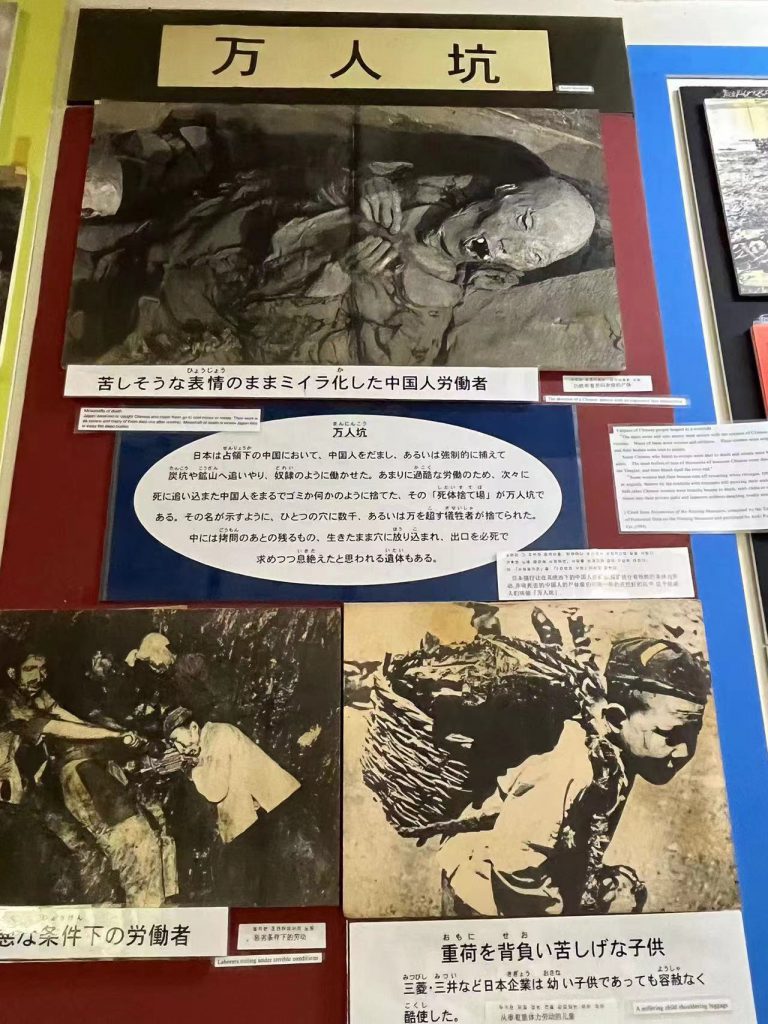

Established in 1995, the Oka Masaharu Peace Memorial Nagasaki Museum exhibits war-time textbooks, photographs, and newspaper articles, mainly about the treatment about Chinese and Korean prisoners of war (POWs).

Upon entering the museum, visitors can find a simulated coal mine depicting the working conditions of the POWs, including maps showing places of origin of Chinese and Korean peasants who were forced to labour in Japan.

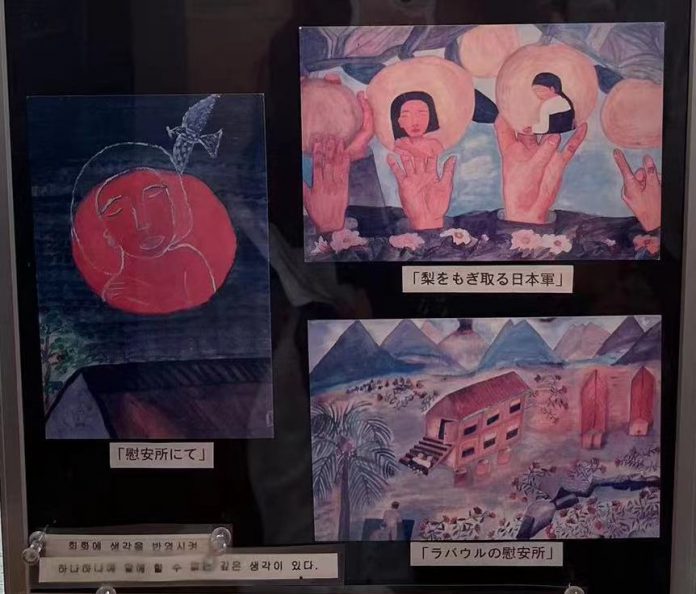

The second floor displays exhibits related to recruiting Chinese and Korean labourers, comfort women, and the Nanjing massacre.

“In creating the exhibition, we aimed to convey accurate facts about the Japanese invasion and understand the pain of those who were affected,” the museum’s website reads.

“The horrors of war and the atomic bomb will always be deeply engraved in our hearts, and we must never let them fade away. However, we must keep in mind that the cause of this tragic outcome was Japan’s brutal invasion of Asia,” it says.

“This humbler museum offers a more nuanced version of history–its exhibits, news clippings and historical documentations cover Japanese armies’ brutality in Asia, especially forced labourers from China and Korea, and comfort women captured in Asia,” says Florence Ng, a visitor to the private museum.

Ng, a former reporter and now an interpreter, adds that the exhibits help her understand why the United States decided to drop an atomic bomb, despite knowing the impact of the bombing.

“The well-documented bad deeds performed by the Japanese imperial armies showed another side of history that is not told in mainstream Japan,” she says.

In response to the exclusion of the Oka Masaharu Peace Memorial Nagasaki Museum in the Nagasaki official guidebook, Discover Nagasaki, the official tourism association of the city replied there is a limit to the amount of information that can be published in the map.

“Popular places are prioritised to be listed, including those with the highest number of current visits and inquiries, and those with a high level of recognition as tourist destinations,” the association says in a written statement.

The country’s history education, however, is trying to hide war crimes committed by the Japanese army, which the private museum tries to reveal to people with its limited resources.

According to the high school textbook syllabus of Japanese History published by Yamakawa Shuppansha, a Japanese history and geography textbooks publisher, the learning points of the Second World War chapter include the Pacific War and the complete collapse of people’s lives. But Japanese war crimes are omitted.

Vickers states it is an undeniable fact that the Japanese civilians suffered in the war with over 80 percent of the buildings flattened.

“The problem is what is left out. It is not the whole story,” he says.

“What the government is doing is not telling outright lies, but they are emphasizing just one part of the war experience,” he adds. “In textbooks, atomic bombs with pictures of the destruction are usually given a double-page spread, with little information on the Southeast Asia invasion.”

According to Vickers, textbooks in Japan are published by private companies, while the government has a committee that vets the textbooks and decides which ones to put on an approved list to be used in education.

“It’s a devious way of covering up what was a massive atrocity committed by the Japanese army,” he says, adding that some local students have no knowledge about Japanese war crime incidents like the Nanjing Massacre.

Teaching politics of history education in Asian society, he observes students are shocked when he mentions how political history education is.

“Such a concept is new to my students. A lot of them had taken it [history education] for granted, thinking that the version of history they learn and portrayed in textbooks is the truth,” he says.

“The idea that history is always being twisted by people in particular agendas is what happens in their history education, and this is something shocking for them,” he adds.

The professor recalls an incident of how Japanese war crimes are being suppressed in society.

“There was a small conference about comfort women organized by the Korean YWCA (Young Women’s Christian Association) in Tokyo five to six years ago. Right-wing demonstrators picketed it and created a disturbance, trying to prevent the conference from proceeding,” he says.

In October 2023, the Oka Masaharu Museum was temporarily closed down due to alleged sexual violence committed by peace activist Oka Masaharu, whom the museum is named after.

Edited by Leopold Chen

Sub-edited by Tessa Yau