The Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum and the Oka Masaharu Memorial Nagasaki Peace Museum, which are just a five-minute walk away from each other, tell different stories of Japan during World War II.

By Lorraine Chiang in Nagasaki

At the heart of Nagasaki, a Japanese city hit by an atomic bomb in the last century, stand two museums showcasing the history of the Second World War with striking differences.

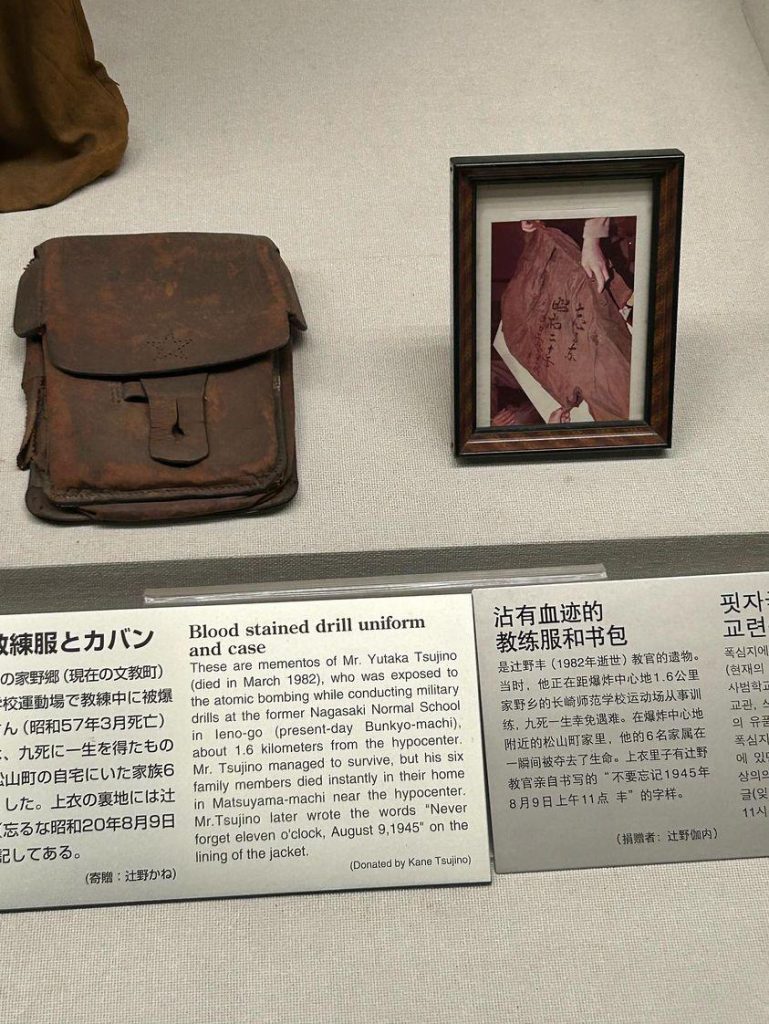

The government-funded Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum is a formidable white structure with carefully curated exhibits placed inside glass casings.

“History is often written by the victors. This is clearly illustrated by the different interpretations of the atrocities of the Second World War by the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum and the Oka Masaharu Museum,” says Florence Ng, a visitor of the two museums.

Opened in 2003, the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum hosts a memorial hall commemorating the victims of the atomic bombing that devastated the city and helped end the Second World War in 1945. But war crimes committed by the country are not mentioned.

“In the official museum, you can see debris from fallen churches and structures, as well as horrific photos and oral history recordings of the civilians injured by the atomic bombs,” Ng says.

“It evokes a sense of anger against the US and empathy towards the civilians in Japan, and it depicts Japan as the innocent victim,” Ng adds.

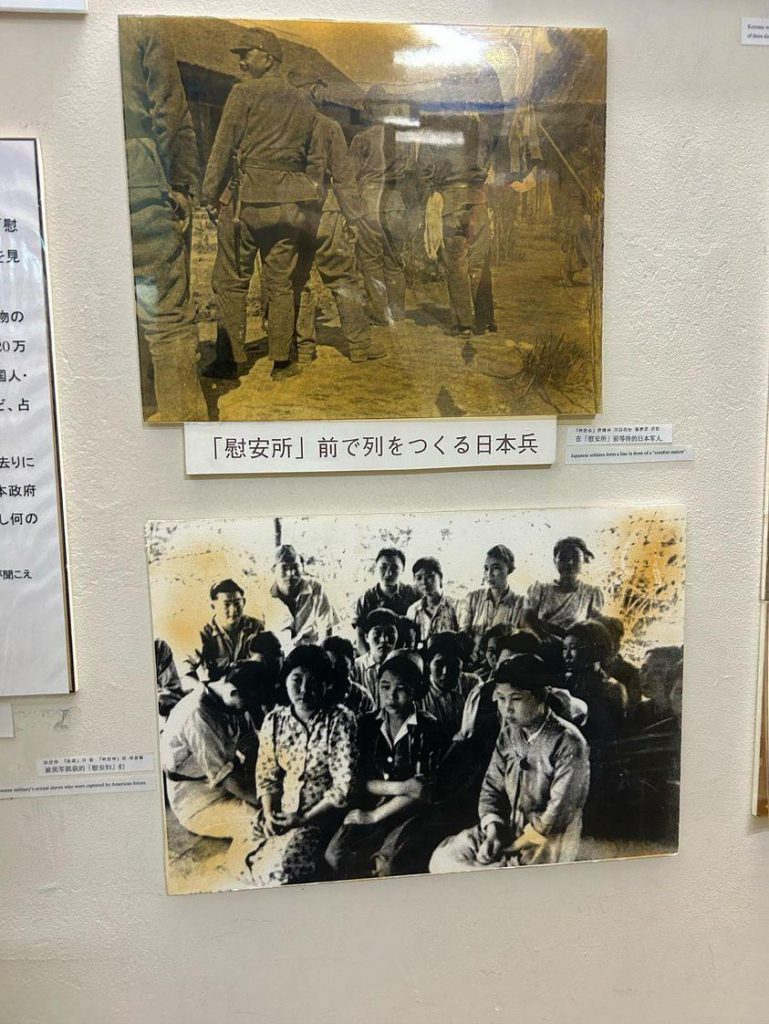

A five-minute walk away from the museum is the Oka Masaharu Memorial Nagasaki Peace Museum. Small and private, it contains exhibits about the causes of the war and the war crimes committed by Japan during the Second World War.

Opening in 1995, the museum shows the meagre portions of food provided for soldiers recruited in China, testimonies from comfort women about their suffering, photos of bodies lying on a bombed bridge in the Nanjing Massacre, and more.

The private museum is also run at a much lower cost. Photos are hung on the walls with yellowing tapes. Only a few are displayed with captions, which are available only in Japanese. Printed sources, such as reports of comfort women, have been flipped through so many times that the pages are immensely wrinkled.

Edward Vickers,the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Chair on Education for Peace, Social Justice, and Global Citizenship, says the public museum is trying to highlight the suffering of Japanese civilians and the fact that Japan is the only country to have suffered an atomic bomb attack.

“Often, people in Korea or China see the history Japan presents as a pack of lies. But it is a fact that Japanese civilians suffered greatly, particularly in the last year or so of the war,” the Kyushu University professor says.

“Japanese cities were completely flattened and destroyed. The bombing that Japan experienced, in terms of its destructiveness, was even worse than Germany’s. Almost all major Japanese cities were levelled, killing hundreds of thousands of people,” Vickers notes.

The professor adds that although the version of history presented by the Japanese government is true, the problem lies in what is left unsaid.

“Most Japanese are not aware of the full horror of what the Japanese army did in China and Southeast Asia,” he says.

According to Vickers, the Japanese government stated the Japanese army was defending Asia from the “evil imperialist West” and that invaded countries were grateful for the Japanese aggression.

Acknowledging that the Japanese people could still learn the other side of history, Vickers argues that they would have to make an effort to do so, as it is not covered in schools, museums, or by mainstream media.

Meanwhile, Germany, as imperial Japan’s wartime ally, allows a much more open discussion about the war and the Nazi era than Japan with its war in East Asia, according to Vickers.

Accounting for the difference, Vickers found the strength of democracy to be a major factor.

“Denazification went a lot further in Germany than similar processes in Japan,” he says.

“In Japan, democratisation was much more limited. They had elections but the same party always wins. Media freedom is also constrained,” he adds.

Joost Schokkenbroek, former director of the Hong Kong Maritime Museum and current museum studies professor at the University of Hong Kong, says the different narratives adopted by different museums could be caused by political reasons.

Schokkenbroek finds it crucial to present a nuanced version of events, as museums are seen as the most trustworthy source in terms of knowledge and narratives.

“There is no proper way to interpret history,” the professor adds.

Citing Canada as an example, Schokkenbroek says the country’s museums only revealed in recent years a history of its indigenous population that were systematically oppressed. They were banned from speaking their own language or displaying their arts.

Giving the oppressed a voice and involving them in museum curation could be a way out to ensure that their viewpoints are seen.

Schokkenbroek finds that many people are not tempted to go to museums because their contents seem irrelevant to current issues.

“It is important for museums to not only focus on beautiful artefacts, exhibitions or letterings, but to keep up with the times by addressing the concerns of young people,” he says.

Edited by Leopold Chen

Sub-edited by Amelie Yeung