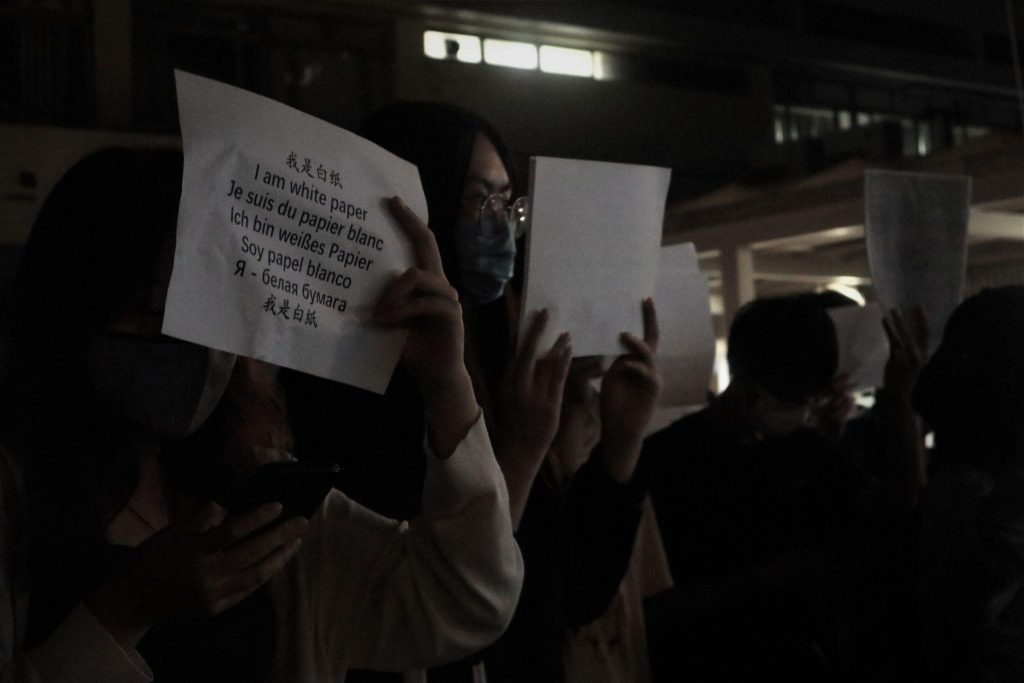

Chinese students took to streets holding blank sheets of paper to voice out anger against “Zero-Covid”.

By Cynthia Chan and Eve Qiao

On the night of November 28, Lu Lin* held a blank sheet of paper on the Chinese University of Hong Kong campus. The act was to express her anger over COVID-19 restrictions and measures in mainland China, which were blamed for delaying firefighters from reaching victims in a deadly fire in Xinjiang.

“I participated in demonstrations in Hong Kong in 2018. I wanted to join protests but did not get a chance back then in mainland China. I saw how well-organised a demonstration was in Hong Kong in 2018 by seeing how the Hong Kong police maintained order. But I am worried about being arrested by the police now. It was safer when there was no National Security Law in Hong Kong,” Lu says.

“But fear is not a reason for not speaking up. It is the responsibility of a university student to care about society,” the year four social science major student says.

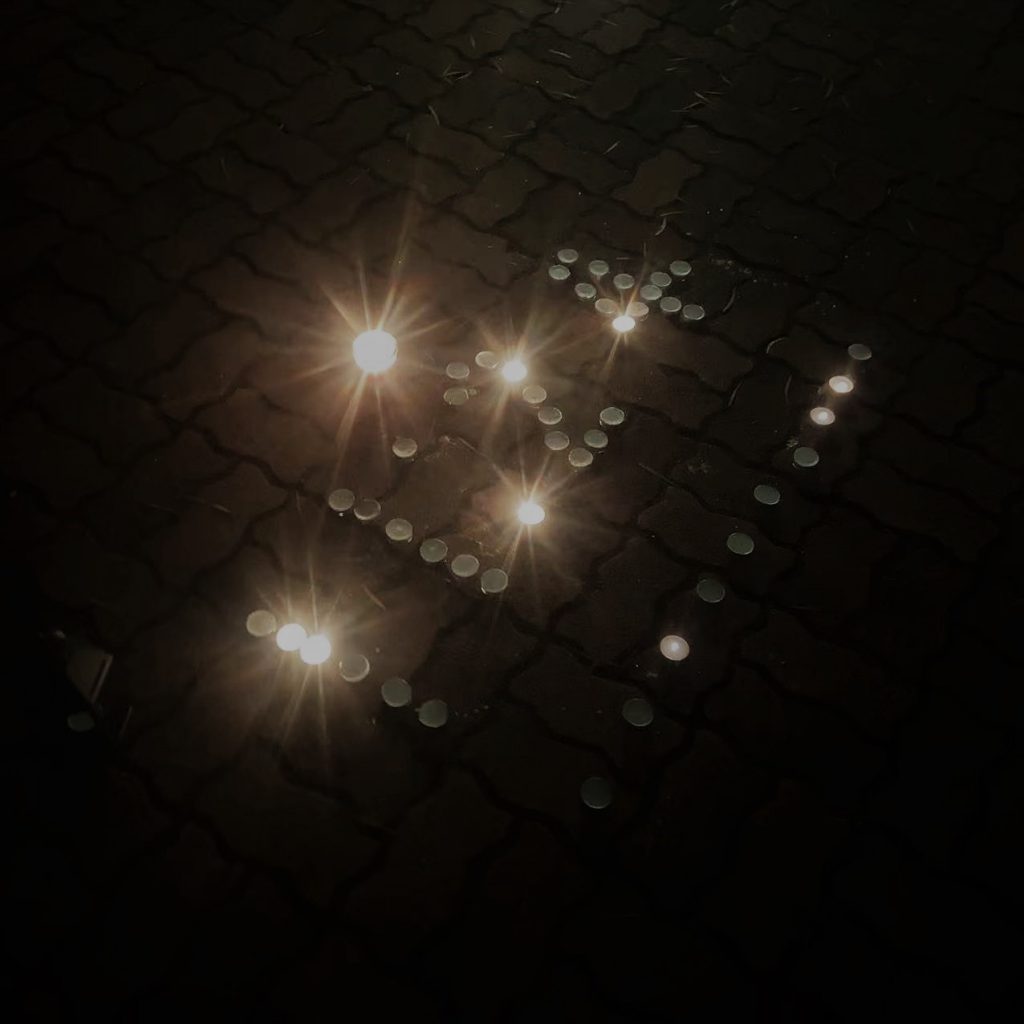

Lu and other students organised a candlelight vigil on November 28, four days after the deadly fire in Xinjiang. According to media reports and videos circulated on various social media platforms, the fire broke out on November 24 in a residential building in Urumqi reportedly. It killed more than 10 people, including four children, as firefighters were not able to rescue the residents because of lockdown measures in the area.

Around 50 to 60 students joined the candlelight vigil as Lu recalls. They sang songs like “Do You Hear the People Sing” and “The Internationale” and chanted slogans such as “We do not want PCR tests! We want freedom!” and “We want to watch films and dine out!”

“I wanted to cry when I heard those slogans. It reminded me of suppression under the party’s rule when I stayed in the mainland,” Lu says.

“I have prepared for the worst. I am ready to face arrests or to run away from the site anytime. We also contacted some lawyers beforehand in case we were arrested,” she adds.

Waves of protests erupted in different cities in China such as Beijing, Shanghai, Nanjing, Chongqing, Xiamen. Citizens and students took to streets and protested on university campuses to voice out their anger against the Chinese government’s COVID-19 restrictions.

The Chinese government announced relaxation of epidemic control policies in a statement released by the State Council on December 7, two weeks after the people took to the street. Measures such as compulsory quarantine arrangement for those tested positive cases were lifted and negative PCR test results to travel across cities were no longer required.

“My father in Chengdu does not need to do daily PCR testing anymore. He had been doing that every day for more than two months before the change of policy came,” Lu says.

“Relaxation of restrictions came all of a sudden. The government has exhausted most medical resources after three years and now it has no choice but to lift the ban. I organised a mass gathering in Hong Kong to fight for freedom and democracy. But these values can not coexist with their version of patriotism in China as the Chinese government gives no room for those values,” she says.

Another university student Sherry Zeng*, who is studying in Hong Kong, also took part in a candlelight vigil on the Chinese University of Hong Kong campus on November 27 to vent her anger and grief about the tragedy in Xinjiang. This is her first time taking part in such an event.

“I felt pain when I first read about the fire in Urumqi on social media…but I dare not to attend mass gatherings as I am afraid of being caught. I want to graduate on time,” Zeng says.

“Lighting up candles is the safest way to express my feelings. I want to fight for freedom of speech and thoughts. I love China but not the government. My actions are expressions of my love for my country,” she adds.

Zeng, who is from Shenzhen, says local authorities announced that COVID-19 restrictions would be relaxed on December 8. Negative PCR test results are no longer required before entering indoor premises, and infected patients can be quarantined at home.

“I think the change in policy has something to do with protests in China,” she says.

University student Chen Heitou* witnessed a protest organised by his classmates at the university campus on November 27 for the first time.

“I learnt about the gathering from our hostel’s WeChat group. I went there with my camera,” says Chen, who is studying in Guangdong.

Standing at the front of the crowd with his camera, Chen took video of five students holding blank sheets of white paper and chanting slogans like ‘Why do we need to seek approval for seeing doctors outside school?’ and ‘Why are our opinions ignored?’ to vent their anger and frustration about the school policy.

“Some asked party leaders to step down. One girl shouted ‘My university life is ruined,’ with a crying voice,” he recalls.

Chen says the school has relaxed some restrictions, such as allowing more students to leave the campus a few days after the protest. Students leaving the campus needed to submit hard-passed applications from August to November in 2022.

Restrictions in Chen’s hometown, Haikou, Hainan have also been relaxed.

“Hainan is a tourist attraction and now tourists from other provinces are not required to undergo mandatory quarantine,” he says.

Chen thinks the protest may be one of the reasons that helps push for the change of policy.

“I think (the protest) may have contributed to the relaxation of restrictions, but it did not play a big role because I believe the state has its own considerations. It is impossible to make such a big change based on the opinions of some groups,” he says.

Chen says he and his schoolmates do not use the word “protest” to describe the action. They use words such as “that night” and “make your voice heard” when they refer to the night when they protested on campus.

“Before the protest, I understood ‘protest’ as a fierce confrontation between people and government and only happens outside China. But after that night, I feel like that protest is about people who have suffered and want to get an explanation of the unreasonable restrictions,” Chen says.

“To me, the protest is a way to vent out our long-accumulated dissatisfactions since the outbreak of the pandemic,” he says.

*Names changed at interviewees’ requests.

Edited by Ella Lang and Ryan Li

Sub-edited by Chaelim Kim