Leisure travellers are experiencing a growing fear to set mainland China as their destination to unwind

By Ariel Lai & Tiffany Chong

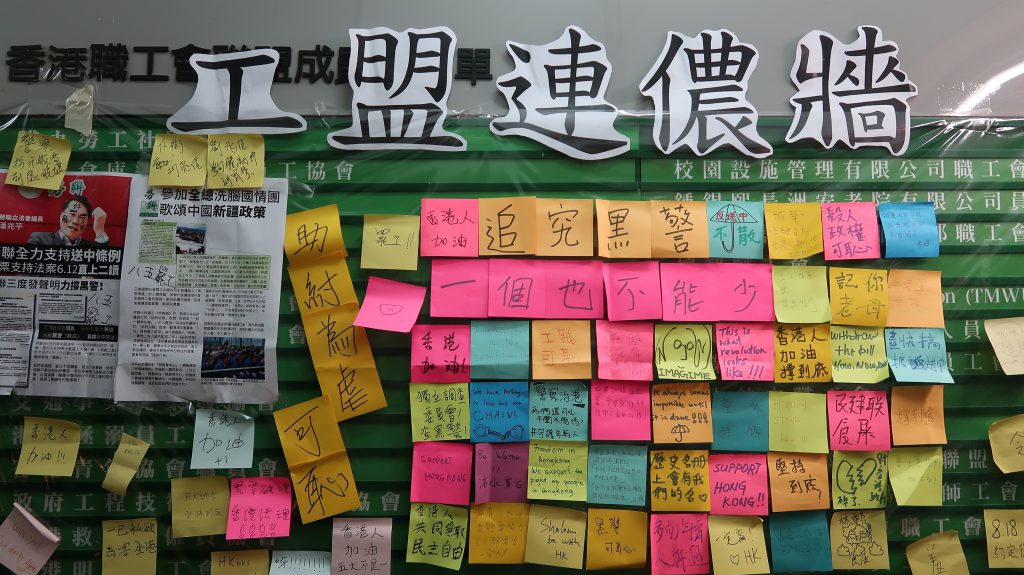

Visiting Shenzhen for a culinary tour or enjoying a hipster lifestyle used to be a quick getaway for Hong Kong people at weekends. Yet, news reports about Chinese immigration officers conducting phone checks at border check points have provoked concerns of privacy and fear among travellers to China, after the anti-extradition bill movement. Social media posts of Hong Kong citizens and foreign visitors being interrogated and required to delete photos and content related to protests in Hong Kong by mainland authorities have gone viral online.

Fear of Leisure Travellers

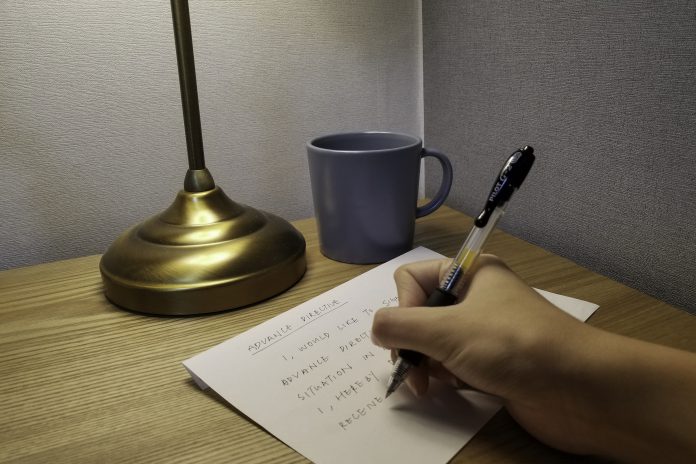

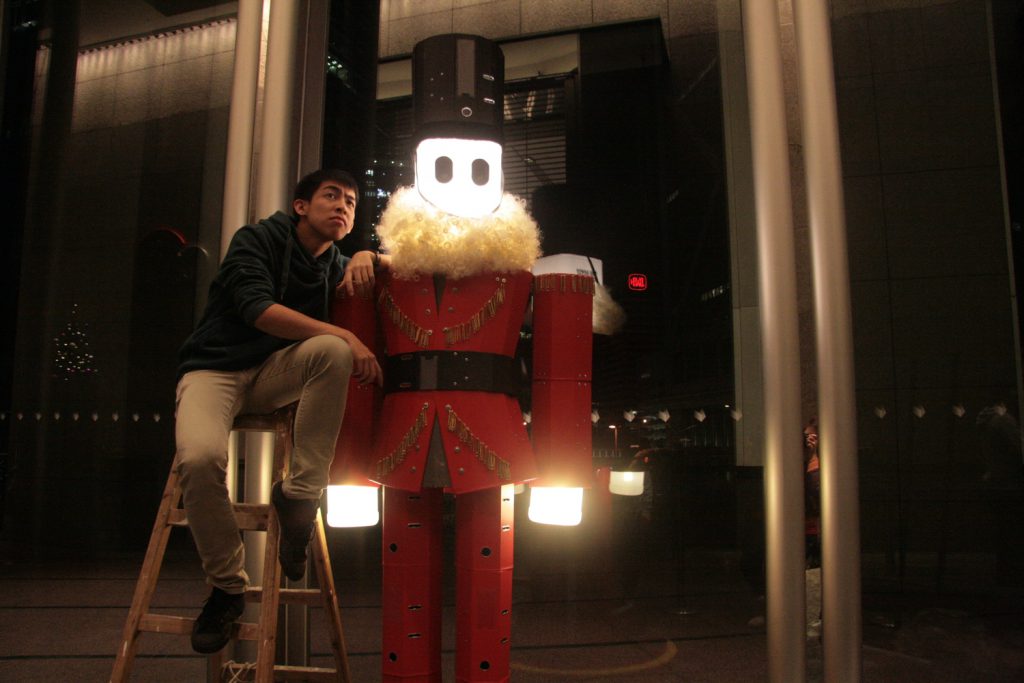

Charlie Ng, 22, shares his unpleasant experience when he crossed the border at Lok Ma Chau. “I will definitely bring a clean work phone or an old phone only. You cannot say no (when being told) to unlock your mobile phone at the border,” Ng says. He recalls walking pass the Lok Ma Chau Control Point with his friend of similar age, a mainland officer stopped and led them to a temporary checkpoint. Ng describes the checkpoint as a tent-like station with four sides surrounded by black nylon fabric that has separate inspection booths inside.

“I have done a lot of research in LIHKG and have known that I am likely to be inspected so I just brought a work phone,” Ng adds. Ng explains he did so as his work phone contains no politically sensitive photos or videos. He recalls being questioned by a female inspector about his purpose of visiting Shenzhen and browsed all his social media apps, particularly the photo album. The inspector also searched his bag to see if there was another personal phone. After this incident, Ng says he will avoid or postpone any trip to China from now on.

Similar to Ng, Karen Wong Tsz-ying, 23, also had her bag checked at the Huanggang Port in August. The mainland authority inspected her large-size luggage with only snacks and drinks. To protect her privacy, Wong deleted all messages and deactivated her Facebook and Instagram accounts before travelling to the Mainland. “I am afraid of visiting China now. My major concern is phone check. I am also worried of being asked to film taped confession or being interrogated (by mainland officers),” Wong says.

Carrie Ho, 22, shares the same fear with Wong. Ho used to visit Shenzhen with her friends once every two to three months. She has stopped travelling to Shenzhen since June. “I am afraid of being arrested or stopped by mainland officers,” Ho says. Although she did not experience any phone checking at the border, she did not want to risk the chance of possible detention.

Privacy Protection

Posing as a customer, Varsity calls several major travel agencies in Hong Kong to see whether escorted tours encounter similar situations when crossing the mainland border. A staff member from Wing On Travel replies that their tours to China are not affected and there is no reported case of phone check at the border. A China Travel Service Hong Kong staff member reminds travellers of the risk of phone checks at the border, especially young travellers. She says travellers are advised to bring another phone without sensitive content when visiting China. An EGL Tours frontline staff member also suggests turning off the phone and deleting all sensitive messages before entering the Mainland.

precaution to protect their privacy

Service Tours Affected

Leisure travellers are not the only ones who have fear of visiting the Mainland. Organisers of voluntary services also become more vigilant when they plan service tours to China.

Posing as interested participants, Varsity calls VolTra, a local voluntary organisation offering service tours to the Mainland and overseas, to inquire about their service tours in China. VolTra replies that they observe a decreasing trend of service tours to China. Due to the recent border check issues, the group says student bodies prefer organising service tours to other Asian countries. Southeast Asia becomes a popular alternative to China given impact on budget is minimal.

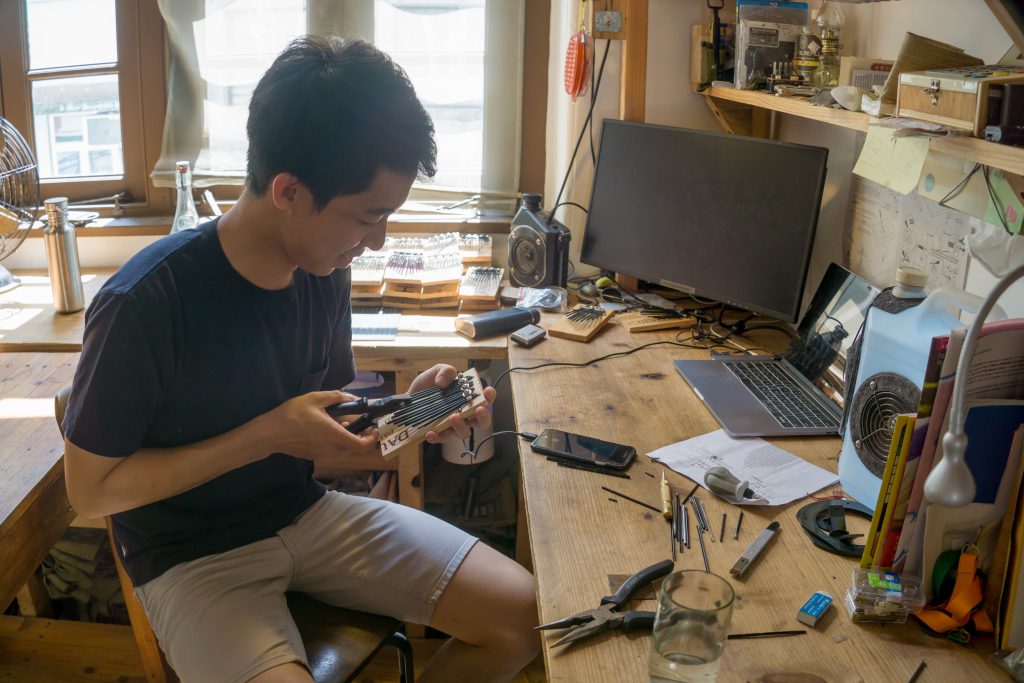

While some voluntary organisations may avoid opting the Mainland as the service destination, some are still organising service tours to the Mainland. One of them is Wu Zhi Qiao Volunteer Team of the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHKWZQ). Funded by Wu Zhi Qiao (Bridge to China) Charitable Foundation, CUHKWZQ is a team of university student volunteers who design and build footbridges in remote areas in the Mainland.

CUHKWZQ finds some students have safety concerns even though they are interested in this project. “We received an email asking whether we would choose another location for the voluntary service given the recent political environment in Hong Kong,” Cindy Kwok, a core member says.

Kwok adds Wu Zhi Qiao (Bridge to China) Charitable Foundation has reminded their team to avoid bringing books and newspapers which might be classified as politically sensitive by the mainland authorities.

Comparing to the same period last year, Selena Chau, another core member of WZQCUHK says it is harder for them to recruit new committee members because the core members are usually the main task force of the voluntary team. “When the members are chatting among the team, we remind each other to be careful. Some members mentioned that they will bring two phones. And others will delete photo albums and social media apps,” Chau says.

Suggestions from the Authority

A spokesperson from the Communication and Publication Affair Section of Immigration Department says they do not receive any reports about phone checking. Since Hong Kong does not have jurisdiction of the border in China, the Immigration Department will not be informed whether there is any inspection at the mainland checkpoint.

“In case travellers are detained at the border, they can approach their lawyers, the Mainland Public Securities and Hong Kong customs or police near the border, depending on the nature of services they need,” the department says.

Edited by Ada Chung