Freedom of speech is under China’s pressure in the workplace in Hong Kong.

By Lasley Lui & Regina Chen

Dismissal for Facebook posts

On August 27, Cathay Dragon flight attendant Mixe Lee received a call from his company asking him to return to Hong Kong at once upon his arrival at a hotel in Shanghai.

While waiting for his return flight, Lee received another call from his former colleague Rebecca Sy, former Cathay Dragon cabin crew union chairwoman who was dismissed by the company after posting three Facebook posts related to the anti-ELAB movement in her private account. Sy voiced her support and gave Lee some advice. “She was even more nervous than me,” the 30-year-old ex-steward recalls.

The following day, Lee attended a meeting with his bosses who showed him screenshots of two Facebook posts and asked him if he wrote those posts on the social media platform. One was about alleged police brutality against pro-democracy protesters.

Lee denied writing those posts, though he actually did. Knowing how Sy was sacked, Lee wanted to explore another way of dealing with the interrogation to see if the result would be different. He was then asked to submit an explanation letter within 48 hours to provide evidence that could prove the Facebook posts were not written by him.

On September 5, Lee attended another meeting with managers to learn that he was sacked.

He demanded the reason for his contract termination. “I can’t tell you anything about it,” said one of the managers. Lee walked out of the meeting room and broke down in tears in front of his colleagues who were waiting for him there.

“I felt so disappointed and shocked during the meeting,” Lee says. He handed in his staff ID card and waved goodbye to his three-and-a-half-year career in the sky.

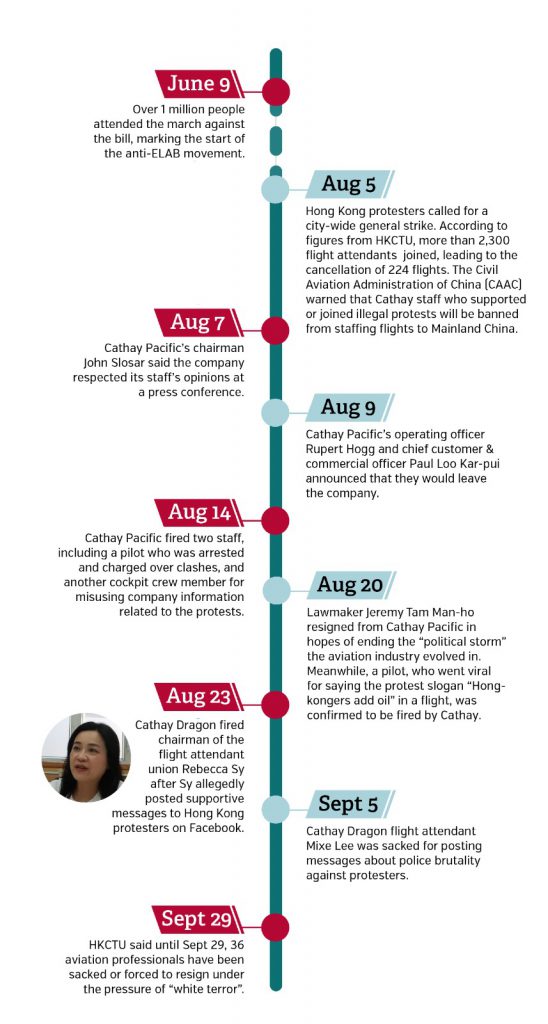

“White terror” in the airline industry

Lee is not an isolated case. According to Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions (HKCTU), until September 29, 36 aviation professionals have been sacked or forced to resign under similar situation, including 26 from Cathay Pacific and six from Cathay Dragon, the airline’s regional arm which operates most of the Cathay group’s flights to Mainland China.

Carol Ng Man-yee, head of HKCTU, criticises the carrier for spreading “white terror” among its employees to suppress freedom of speech. “The so-called white terror can make people censor themselves, regulate themselves and eventually silence themselves,” the labour activist says.

Cathay comes under pressure from China, which has become a major source of tension. On August 9, the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) issued a severe aviation safety risk warning to one of the world’s top airlines based in Hong Kong that does business with China, stating that Cathay employees who “support or take part in illegal protests, violent actions, or overly radical behaviour” will be banned from staffing flights to Mainland China or using Chinese airspace.

Later that same day, in response, a Cathay spokesman said: “There is zero tolerance for any inappropriate and unprofessional behaviour that may affect aviation safety.” The company has also updated its employee guidelines that include a section on social media posts, encouraging staff to “speak up” via the whistle-blowing policy if they see any breach of the code of conduct or the law.

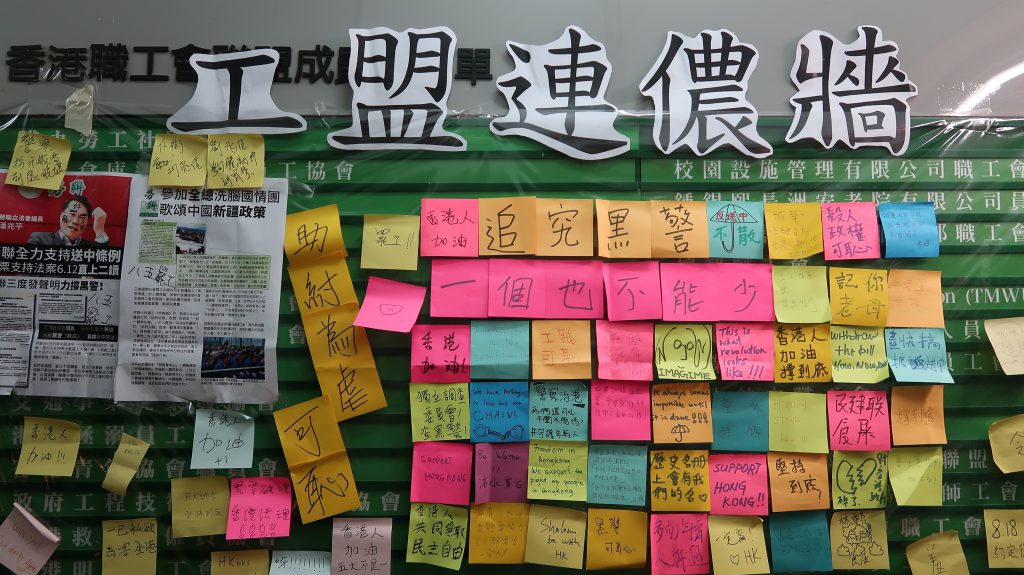

Since Hong Kong’s anti-ELAB protests broke out in June, the airline industry has been actively playing a role in the city’s large-scale social movement. Aviation workers launched two online petitions, calling upon the government to respond to protesters’ demands. They also organised a peaceful assembly themed “Fly with You” at the airport in July, attempting to draw international visitors’ attention to Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement.

On August 5, protesters kicked off a citywide general strike, in the hope of pressing the government to make changes. Ng recollects that as soon as the clock struck midnight, messages from chat groups formed by aviation workers started popping up on her phone. Ng, a former British Airways flight attendant, says that by 2am that morning, almost half of the airport workers who were supposed to report to duty on that day had called in sick. “Even before the rally started, we already knew that the airport employees had announced their victory ,” she says.

Figures from HKCTU suggest that more than 2,300 aviation employees joined the strike, leading to cancellation of 224 flights to and from the international transportation hub. Ng says on a usual day, about 3,200 employees work at Cathay Pacific and 900 work at Cathay Dragon. She believes that about 1,200 Cathay Pacific workers and 590 Cathay Dragon staff did not go to work on August 5. Cathay chairman John Slosar said the company respected its staff’s opinions at a press conference on August 7.

“They eventually got on the Chinese Communist Party’s nerves,” says Ng. Days after the biggest strike in Hong Kong in decades, Cathay Pacific, the most high-profile corporate in the movement, fell victim to Beijing’s pressure on Hong Kong’s businesses. After the CAAC released its directive on August 9, the company’s chief operating officer Rupert Hogg and chief customer & commercial officer Paul Loo Kar-pui stepped down and the number of employees who claimed that they got fired because they supported the protests increased.

Ng thinks the practice of placing workers’ political values above their professionalism is dangerous. Ng says if employers only hire people who are loyal to Beijing, they may place less emphasis on candidates’ professional knowledge. “It concerns safety issues and maintenance of professional standards,” she adds. Ng says many experienced pilots and flight attendants have been sacked during the past several months while they were the backbone of the aviation safety.

Jeremy Tam Man-ho, a member of the Legislative Council and former pilot, resigned from Cathay Pacific Airways on August 20, ending his 18-year career. As a legislator from the pro-democracy camp, Tam says his ties with the company had resulted in attacks from the pro-Beijing camp targeting the airline. He hopes his resignation could help protect the airline from unjust accusation and bring an end to the political gales the aviation industry had got caught in.

The pro-democracy lawmaker observes loopholes in the current law which fails to protect the rights of the Cathay employees who have been sacked for their speech on social media.

Under Hong Kong’s Employment Ordinance, if an employee is dismissed other than for substantial reasons, he or she can claim for reinstatement or re-engagement against an employer for unreasonable dismissal. The Labour Tribunal will issue a reinstatement or re-engagement order if the Tribunal considers that it is appropriate and practicable. The employer shall pay to the employee a further sum, amounting to three times the employee’s average monthly wages and subject to a ceiling of $72,500, if he or she refuses to execute the order.

In 2018, the Legislative Council vetoed the amendments proposed by Labour Party lawmaker Fernando Cheung Chiu-hung who sought to raise the remedy to six times the employee’s average monthly wages and lift the ceiling. Cheung criticised that employers only needed to pay a very low price for rooting out a thorn in their flesh.

“We urge the people to increase the penalty,” Tam says. “But in the Legislative Council, the majority is pro-Beijing. They just don’t want to increase the penalty to protect our employees in Hong Kong.” Tam also points out that the lack of collective bargaining rights is another factor that weakens Hong Kong workers’ negotiation power.

“It is not just Cathay Pacific’s issues,” says Tam. “It can also extend to any other industries, not only the airline [industry].” He cites China’s boycott on Taipan Bread & Cakes and the National Basketball Association as examples. Both of the brands faced backlash in the Chinese market after their executives expressed support for Hong Kong protests on social media. Blizzard Entertainment, the American gaming company, punished a Hong Kong-based e-sports player after he shouted “Liberate Hong Kong; revolution of our time” during a post-game stream.

Freedom trembling with fear

The shifting political landscape and growing strong-arming by China are not only changing the way businessmen do business in the global financial hub, but also fuelling a chilling effect on ordinary people in their daily lives.

Allan Au Ka-lun, professional consultant of the School of Journalism and Communication at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, says that he could not recognise his friends on Facebook because they have changed their names and profile pictures to hide their identities in fear of being reported by acquaintances for posting something that is not in favour of the government.

“It seems like everything is normal, but everything is abnormal,” says Au. “You are afraid of expressing your opinions. You don’t trust other people, your friends, your boss, or even your parents, your relatives.” He says this kind of distrust between people is “terrifying”.

As a former reporter at Television Broadcasts (TVB), Hong Kong’s largest free TV station, which has become the target of protesters after being accused of a pro-Beijing bias, Au makes an analogy between the self-censorship pressure in the newsroom he personally experienced decades ago and the white terror which has recently cast a shadow over many companies in the city. “This is control through organisational fabric,” says Au. “Organisational control is not an explicit threat. No one will tell you what to do or what not to do. No one will tell you [whether] you will be punished,” Au says. He adds what authorities need to do is just to control the boss who has the immense power to decide whom to hire and fire.

He refers the organisational control as party-state capitalism, a term used to describe the economy of Taiwan under the authoritarian military government of the Kuomintang. “You don’t have to use any harsh measures to control people,” Au says. “Once you have money and capital, you can have more civilised ways to control people.”

Au thinks the white terror will not end, and people will get more used to it.

Lee shares Au’s observation that the climate of fear has no end in sight. Lee recalls that many chose to join the airline industry because they thought they could enjoy freedom there. “We can fly to other places, do whatever we want and say whatever we want,” Lee says. “We always speak a lot during the flights. Even if we have different points of view, we can share with each other.”

But after the first dismissal event, a “weird” atmosphere arose among the crew. Lee says they did not chat anymore in the cabin and he could feel the distance between colleagues. “We lost a lot. We lost freedom in Hong Kong. We lost freedom in our company.”

The sudden mishap disrupts Lee’s plan for the future. “I became the collateral damage crushed by the large wheel of politics,” Lee wrote in a Facebook post on September 5, the day he left his once-beloved company.

Edited by Gloria Li