Reporters: Nia Tam and Beverly Yau

While thousands of graduates fill in countless job application forms and ponder their futures every year, other young people are not thinking about finding their dream job but about setting up their own business.

Becoming an entrepreneur may be the realisation of a childhood dream or simply the result of a random opportunity. Here, Varsity talks to three young entrepreneurs, who share the struggles and joys of being their own boss.

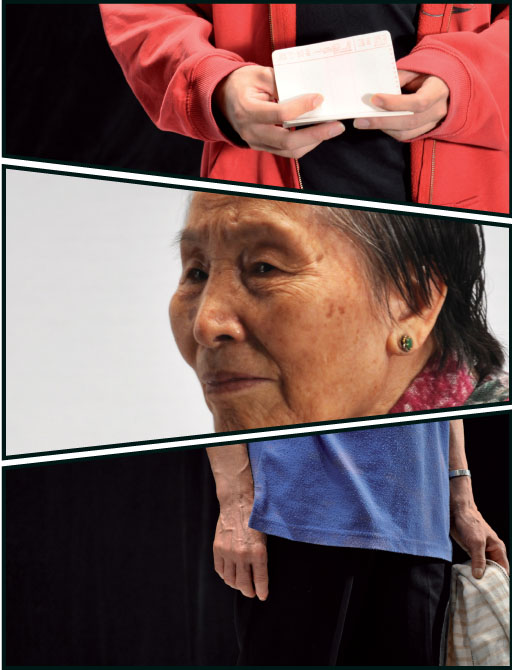

I have dreamt about being an entrepreneur since I was a form three student,” says Eva Chiu Man-wah, the founder and managing director of Etin Hong Kong Limited, a company that designs and manufactures promotional umbrellas.

Now in her early thirties, Chiu was inspired by the female characters in the financial novels of local writer Leung Fung-yee. “All the heroines in Leung’s stories are young, good-looking, talented and most importantly, have their own business,” she adds.

Given her clear sense of purpose, Chiu began preparing herself early. She realised she would need to know how to read a company financial report, so she chose accounting as an elective subject in form four.

After leaving school, Chiu got a job as an accounting clerk for an international company while studying for an accounting degree from The Open University of Hong Kong. At the company, she climbed up the ladder to Accounting Manager, and then worked in various positions in merchandising, retailing, marketing and management.

“I worked as an employee to learn the skills that every position needs. Earning money was just the second most important thing,” she says of her 10 year’s as an employee.

Chiu says those years as an employee were a great help to her when it came to starting and running her own business. She says her management style, which emphasises team work, care for colleagues and effective communication, is modelled on her experience in that international company.

Chiu’s first attempt at striking out on her own was a gift shop. It was while running the shop that she discovered there was a “concealed but profitable market” in promotional umbrellas, printed with the logos of companies and organisations or promoting their products.

So she drew up a proposal for a company to produce promotional umbrellas and submitted it to a competition called Youth Business Hong Kong organised by the Hong Kong Federation of Youth Groups.

Her idea of a physically attractive and practical promotion product won her a loan of $90,000 and advice from professionals. It gave her just the support she needed to start what is now Etin Hong Kong Limited.

Although her family saw her as an independent and capable young woman, Chiu faced strong opposition when she revealed her business plan. Her worried mother told her that she would have a stable income and a future without too many difficulties as an employee.

There were times her mother must have felt vindicated. Chiu recalls the days when she had to constantly commute between Hong Kong and the mainland and work for almost the whole day without any rest. Her weight dropped drastically as a result. Chiu says she had to sacrifice time with her friends and family, but she would not have done it any other way. “Any regrets? No, I don’t have any. I chose my own path and it is worthwhile,” she says.

Neither did she give up when confronted with her biggest challenge and disappointment to date. Not long after the global economic meltdown in2008, Chiu’s good friend and business partner suddenly left Etin and started a rival company, poaching some of the best customers. “Etin is like my baby. I have a responsibility and a sense of mission to protect it,” says Chiu.

Telling herself not to disappoint those who had supported her for so long, she managed to achieve a 50 per cent growth of business in the past year. “My business became even more prosperous after the break up,” she says.

The company is now 15 years old and has been awarded the HSBC Living Business Excellence Award – an award recognising corporate responsibility – for three consecutive years.

Chiu has reached one of her targets, to be able to buy her own office, but she says she will keep advancing herself and her business through life learning. “The hard work is worth it,” she says.