Feminist and LGBTQ+ accounts on Chinese social media have been made disappear.

By Ryan Li

Cat Wang* and some other members of Catch-Up Sisters, a women rights concern group in China, found that they were banned from reposting feeds on their Weibo account (@CatchUp性别公正姐妹) on September 14.

Their official account had around 56,000 followers on Weibo, one of China’s biggest social media platforms, by the time it was suddenly suspended.

“Other users could not view our account page …we were made invisible (in the cyber world),” Wang says in an online interview.

Their Weibo account cannot be searched by other users from then on. A notice saying “the account cannot be viewed because of complaints on violating Weibo’s rules” appears when attempts are made to look for their account.

Catch Up Sisters has long been focusing on feminism and gender issues in mainland China. Their discussion on Weibo covered women reproductive rights, career development and Chinese women’s living conditions in rural areas.

Unclear Reason

Wang received a phone call from Weibo on her mobile number that was connected to their account, telling her to “avoid posting sensitive contents” on the same day.

Wang and her team asked a Weibo staff why the account was suspended, but the staff did not reveal any details.

According to China Digital Times (CDT), a California-based news website aggregating information censored on Chinese internet, at least 47 other Weibo accounts were also suspended that day.

The news website points out these social media accounts might be banned due to the second trial of Xianzi’s case at Beijing Haidian District People’s Court.

“Users who have posted and reposted information regarding the trial or expressed support towards Xianzi were censored,” CDT writes on its website in an article on September 14.

Xianzi, surnamed Zhou, accused Zhu Jun, a famous host at China’s state broadcaster CCTV, of sexually harassing the then 21-year-old intern in his dressing room in 2014. The case was seen as a landmark of China’s #MeToo movement and feminist campaigns.

Wang also suspects that their Weibo account ban was related to Xianzi’s case, as the account reposted two posts supporting the plaintiff on that day.

This is the third time Catch Up Sisters’ account has been suspended since the team’s establishment in 2016. Their previous two accounts were forcefully closed respectively in 2019 and April of 2021. No reason was given.

“We were very angry after the first two suspensions, but we are rather calm this time. We somehow get used to it,” Wang says.

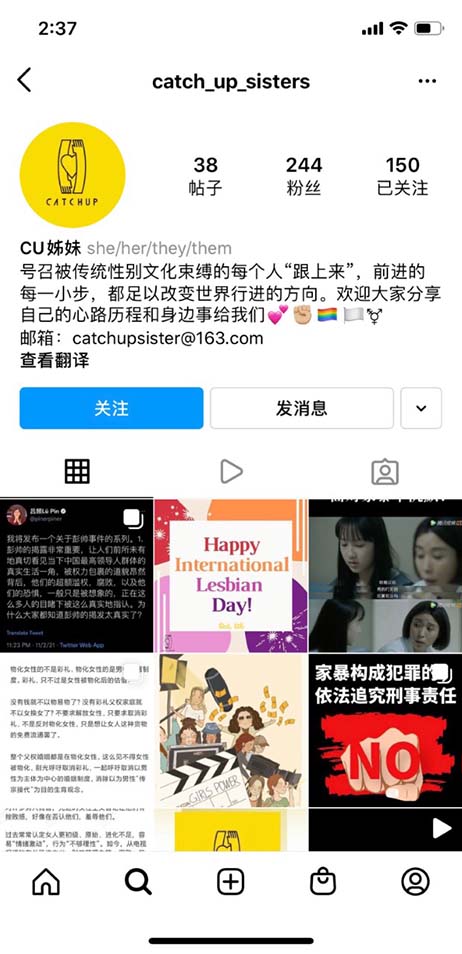

The group used to create new accounts using the same logo and adapting subtle changes to the user’s name to restart the operation. They did the same soon after the incident on September 14, but the new account (@CU姊妹) was immediately suspended, without posting anything.

“WE WERE VERY ANGRY AFTER THE FIRST TWO SUSPENSIONS, BUT WE ARE RATHER CALM THIS TIME. WE SOMEHOW GET USED TO IT.”

They opened Twitter and Instagram accounts afterwards by migrating contents from their previous accounts. “We don’t want to waste our years of efforts made in building the account,” Wang adds.

Another Victim

Apart from social media accounts related to Metoo and feminism, discussions related to sexual minorities are also considered as sensitive contents.

On July 6, 2021, several public accounts related to sexual minority issues run by students across Chinese universities were suddenly suspended, including Purple at Tsing Hua University, Colorsworld at Peking University, and Zhihe Society at Fudan University. Their original account names were replaced by “unnamed public accounts”, which later was used by netizens to refer to the suspension of all the social media accounts by university students.

Zhihe Society, a student association at Fudan University in Shanghai focusing on gender and LGBT+ issues, also has similar experience. The society’s WeChat public account “ZhiheSociety at Fudan University” (復旦大學知和社) was suspended on July 6, 2021.

The account run by several Fudan University students hosted discussions which were academic in nature, providing readers with information including academic papers and sharing sessions related to gender or sexual minority topics, according to Jamie Cai*, one of the former core members of the society serving from September 2020 to September 2021.

“We received no notice of any kind. Our public account’s main page was turned to a total blank, leaving a message saying that our account ‘has violated rules of the Administration of Internet News Information Services’,” Cai recalls.

Cai says the team of core members decided not to make an appeal. “We thought that was no use,” he adds.

Established in 2005, Zhihe Society has been officially registered as a formal student association under Fudan University’s Youth League Committee Office. “We are one of the first LGBT-related student associations recognized by the university,” Cai says.

But their move was under the office’s close control. “They (the office) will try hard not to approve any of our offline events. Prevention of COVID-19 outbreak was always cited as the reason or should we say their excuse,” Cai says.

The society’s main social media account on WeChat was also under surveillance. The public account shared a notice in January 2021 about an upcoming sharing session on feminism at Fudan University featuring Wang Zheng, associate professor at the University of Michigan who researches feminism in China.

“Around five minutes after we published the notice, we received a phone call from the office asking us to delete it,” Cai says. “The reason given was that Professor Wang was not in a good relationship with the university,” he adds.

According to Cai, the Committee Office at Fudan University was not involved in the society’s WeChat account suspension on July 6, indicating the decision was not made by the school, but by WeChat instead.

“They (the office) had no idea about the incident when we first approached them to ask what had happened after being suspended,” Cai says.

After two months of “disappearance”, Zhihe Society resumed operation on WeChat in September 2021, using a back-up account created in 2017. In a post on September 10, the association introduced what they have done in the past two months and called for students to join them at the beginning of the school year.

Voice or Noise

Guo Lifu, a PhD student at the University of Tokyo, who has been researching LGBT+ movement and queer politics in China since 2015, finds the Chinese authorities have become more cautious about feminism and LGBT+ movement.

Guo says the current tension between China and the U.S., and Chinese president Xi Jinping’s strong attitude towards western ideologies, “have together turned these (feminism and LGBT+) issues into bargaining chips during the competitive race between the two world powers.”

“Feminism and LGBT+ thoughts are indeed imported to China from western societies. These are not included in the system of the China Communist Party, symbolizing democratization that they fear,” he adds.

“In Chinese social media ecology, some netizens even do not even know what feminism or LGBT+ rights really are. They just showcase their patriotism and anti-U.S. emotions through opposing these ‘western’ thoughts,” says Guo, viewing the situation as a consequence of “political framing”.

“FEMINISM AND LGBT+ THOUGHTS ARE INDEED IMPORTED TO CHINA FROM WESTERN SOCIETIES. THESE ARE NOT INCLUDED IN THE SYSTEM OF THE CHINA COMMUNIST PARTY, SYMBOLIZING DEMOCRATIZATION THAT THEY FEAR.”

Fang Kecheng, associate professor from the School of Journalism and Communication at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, believes the censorship cannot completely suppress these voices, as “feminism is about women’s daily lives and can cover a wide range of social issues.”

For feminist and LGBT+ social media accounts, Fang suggests that they should try to stay flexible, for example, try creating more diverse content which focuses on individual experiences and stories considered less sensitive.

“Forming deeper connections with more people within a relatively small range may work better under the current situation,” he says.

Where is Peng Shuai? Chinese Player Not Seen Since Post About Sex Assault

Peng Shuai, a Chinese top tennis player, accused the country’s former vice premier, Zhang Gaoli, of forcing her to have sexual relations in a post on Weibo, China’s Twitter-like social media platform, on the night of November 2, 2021.

The original post was quickly removed and cannot be viewed by users. Comments on Peng’s account were turned off. According to China Digital Times, names involved such as Peng Shuai, Zhang Gaoli and Kang Jie (Zhang’s wife) were listed as sensitive keywords and strictly censored.

In the 1600-word post, Peng said she had a three-year lover relationship with Zhang with knowledge of Zhang’s wife, Kang Jie. Zhang has not responded to the accusation so far.

Steve Simon, chairman and chief executive officer of Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) made an announcement on the organization’s official website calling for “full, fair and transparent investigation” into the allegations on November 14.

Peng was away from the public eye after she made the allegations on Weibo. On November 17, after Peng’s two-week disappearance, China’s state affiliated media CGTN posted a screencap of Peng’s “email to Steve Simon” on its Twitter account. The picture attached refuted previous allegations, adding that WTA should “verify” with her before posting any further news without her consent. However, WTA said the video was “insufficient evidence” of Peng’s safety.

On December 1, WTA announced immediate suspension of all tournaments in China, including Hong Kong.

Chinese feminism accounts on Instagram have paid great attention on Peng’s safety. Feminist China, based in the U.S., organized both online and offline campaigns including “#Where is Peng Shuai” to support Peng and demand justice.

*Names changed at interviewee’s request

Edited by Coco Zhang & Lynne Rao

Sub-edited by Fiona Cheung