Rich Chinese demand more quality nursing homes.

Lily Wang

Wang Ziqiang, a 54-year-old businessman, has been paying an annual deposit of RMB ¥100,000 (US $15,740) for an 85-square-metre room in an elderly home in Zhejiang province since 2019.

In total, he has to pay RMB ¥1.5 million (US $15,740) in 15 years before he and his wife can live there when they are in their 60s.

“I made the payment for my mom, who is now in her 70s. But she refuses to move in. So I decided to change the plan for myself and my wife,” Wang says.

“I thought it would be good for my mom and my wife. My wife keeps saying she is tired of taking care of both my mom and two children. My younger daughter is just seven,” he adds.

The nursing home which Wang and his wife plan to move in is still under construction. He might have to settle other payment which is now unknown to him in the future.

Wang says the institution provides medical service, housekeeping service, and catering service, but charges of these services are not confirmed yet. “I also have to pay for other services my wife and I need in the future,” Wang says.

Despite all the uncertainties, Wang still considers spending his retirement life in a nursing home a good idea.

“I think it is worth it. The fee will be higher if I want these services at home. It is difficult to hire a good domestic helper, and expensive to hire medical professionals to work at home. I do not want to burden my children,” he says.

“It is difficult to hire a good domestic helper, and expensive to hire medical professionals to work at home. I do not want to burden my children.”

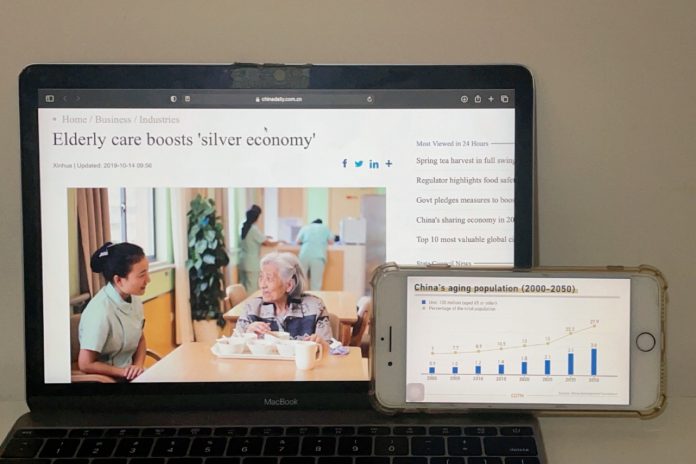

There were more than 260 million aged over 60 in China, accounting for 20 per cent of the whole population, while the birth rate was less than one per cent, according to the National Bureau of Statistics in 2020.

By the end of 2020, there were 38,000 nursing homes for the elderly in China, marking an increase of over 37 percent since 2015, while the number of beds jumped by 7.3 per cent reaching 8.24 million, according to Li Jiheng, minister of civil affairs, who attended a press conference in February 2021.

“It is highly likely that my children will have to take care of at least three elderlies. One of my children will have to take care of me and another will take care of my wife. They also have to take care of their future parents-in-law, Wang says.

Mike Chen, a senior manager of a nursing home for old people from well-off families in Xiaying, Ningbo, says living in nursing homes that offer quality services is quite a popular choice for elderlies from affluent families like Wang’s.

“Our rooms were rented out quickly. As there have been more incidents about conflicts and tragedies involving families and their domestic helpers who are hired to take care of the elderly reported in the press, many families have started looking for alternative retirement living options,” says Chen, who has eight years of experience in the elderly care industry.

“As there have been more incidents about conflicts and tragedies involving families and their domestic helpers who are hired to take care of the elderly reported in the press, many families have started looking for alternative retirement living options.”

The nursing home Chen works at has a building in the complex with all kinds of medical facilities prepared for clients with serious illness. “Many families cannot take care of their loved ones with serious illness, and we have a team of medical professionals who can help them,” he says.

Chen says a contract is signed between the nursing home and clients. “We guarantee our clients can live here until they pass away. Their children can also live here as long as we have the capacity to provide them the service,” he adds.

When asked how nursing homes can fulfil all their promises for their clients who have to start paying more than a million before they can move in, Chen remains silent.

Kong Xianglai, a lecturer teaching economy at the Zhejiang University of Science and Technology, points out that the ageing population in China has created business opportunities for this kind of nursing home.

“There are some problems in the system, such as the payment method. But we still see nursing homes flourishing, showing that there is a strong demand for such service,” Kong explains.

“The well-off families can afford high-quality service. They, in this case, can be considered as the demands, and institutions like these nursing homes offering quality service can meet their demands. They form a perfect economy,” says Kong, who does research on elderly population.

Kong says sending parents to nursing homes does not necessarily imply that their children do not love them.

“This kind of love can be understood in two ways. On one hand, children want their parents to have better service and care. On the other hand, parents want to move in so that they will not burden their children. It is almost impossible to ask a working middle-aged person to give up everything in his life to only take care of his parents,” Kong says.

But Kong thinks the ageing population should not be considered a problem. “People often view elderly people as burdens. They are old, but it does not mean they have no value. Actually, many elderly people can continue to work,” Kong says.

“People often view elderly people as burdens. They are old, but it does not mean they have no value. Actually, many elderly people can continue to work.”

Currently, the retirement age in China for men is 60 while for women is 50. The government is exploring the possibility of extending the age to 65.

“Elderly people are being stereotyped. If more jobs can be provided for them so that they can live on their own, the problem of the ageing population in China might be alleviated,” he says.

Edited by Kajal Aidasani

Sub-edited by Leung Pak-hei